Impact of Endoscopic Surgical Skill Qualification System-certified surgeons as operators in laparoscopic rectal cancer surgery in Japan: A propensity score-matched analysis (subanalysis of the EnSSURE study)

Abstract

Background

In Japan, the Endoscopic Surgical Skill Qualification System (ESSQS) is used to evaluate surgical skills essential for laparoscopic surgery, but whether surgeons with this certification as operators improve the short-term outcomes and prognosis after rectal cancer surgery is unclear. This cohort study was designed to compare the short-term and long-term outcomes of laparoscopic surgery for advanced rectal cancer performed by an ESSQS-certified surgeon versus a surgeon without ESSQS certification.

Methods

The outcomes of cStage II and III rectal cancer surgery cases performed at 56 Japanese hospitals between 2014 and 2016 were retrospectively reviewed. To examine the impact of ESSQS-certified surgeons as surgeons, the outcomes of cases with only ESSQS-certified surgeons as operators were compared with those without involvement of ESSQS-certified surgeons.

Results

A total of 3197 cases were enrolled, with 1015 in which surgery was performed by ESSQS-certified surgeons, and 544 in which there was no involvement of ESSQS-certified surgeons. After propensity score matching, the ESSQS group had significantly shorter operative time (p < 0.001), a lower conversion rate to open surgery (p < 0.001), and more dissected lymph nodes (p = 0.002).

Conclusion

Laparoscopic rectal surgery performed by ESSQS-certified surgeons was significantly associated with improved short-term outcomes. This demonstrates the utility of the ESSQS certification system.

1 INTRODUCTION

Laparoscopic colorectal resection has been shown to have superior short-term and noninferior long-term outcomes compared with open surgery and is widely performed around the world. The short-term and long-term benefits of laparoscopic colon resection performed by expert surgeons have been reported in Japan.1, 2

The indication for laparoscopic colorectal resection has been extended to the rectum, and more than half of all rectal cancers are now treated laparoscopically.

Several countries have established training programs and qualification systems to ensure the quality of laparoscopic techniques.3, 4 The Japanese Society for Endoscopic Surgery (JSES) established the Endoscopic Surgical Skills Qualification System (ESSQS) in 2004 to certify the skills of surgeons who have achieved a certain level of technical skill and teaching ability in their field. Board Certified Surgeons of the Japan Society for Endoscopic Surgery (JSES) who have achieved the required surgical experience and academic achievements and have attended seminars organized by the JSES are eligible to apply for the certification examination. The technical examination involves evaluation of unedited videos of laparoscopic sigmoid resection or high anterior resection, the basic laparoscopic surgical technique. Video reviews are conducted as random reviews performed by two–three surgeons who are qualified JSES reviewers. Only 20%–30% of applicants are accredited, and qualified ESSQS surgeons are recognized not only as surgeons who can independently, safely, and accurately perform laparoscopic surgery for colorectal cancer, but also as instructors. There have been several reports of the benefits of ESSQS qualification for colorectal cancer, all of which were small, retrospective cohort studies.5, 6 The usefulness of ESSQS certification for rectal cancer was until recently unknown, because the proportion of laparoscopic surgery for rectal cancer to total colorectal cancer was small during the period covered by previous reports. We demonstrated that the involvement of ESSQS-certified surgeons in laparoscopic rectal surgery as operators, assistants, or advisers reduced the postoperative complication rate in 56 centers belonging to the Japanese Society for Laparoscopic Colorectal Surgery (JSLCS).7 The results suggested that the involvement of ESSQS-certified surgeons in surgery as operators, assistants, and advisers may improve surgical outcomes. The analysis also found that the ESSQS-certified surgeon as an operator did not reduce the risk of postoperative complications, while the ESSQS-certified surgeon as an assistant significantly reduced the risk of postoperative complications. As a secondary endpoint of the same analysis, there was a significant advantage of the ESSQS-certified surgeon in open conversion, operative time, blood loss, and R0 resection when more than one ESSQS-certified surgeon participated in the procedure as operators, assistants, and advisers, and the impact was highest in the open conversion. The purpose of the current analysis was to examine whether there are any advantages of an ESSQS-certified surgeon among these four outcomes, when only one ESSQS-certified surgeon participated in the procedure as an operator. We hypothesized that the ESSQS-certified surgeon as an operator had impacts on reducing the rate of open conversion and set the open conversion as the primary endpoint of the current study.

2 METHODS

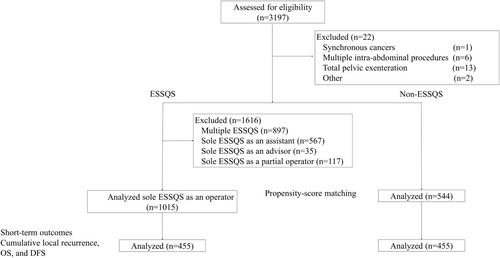

The study was conducted as a subgroup analysis of the main cohort study (EnSSURE study), a retrospective cohort study in which all elective laparoscopic rectal resections performed at 56 hospitals belonging to the JSLCS were retrospectively reviewed. Details of the study protocol have been previously published.7 Laparoscopic rectal resections for Stage II or III rectal cancer performed between January 2014 and December 2016 were included. To assess the utility of ESSQS-certified surgeons as operators, cases with multiple ESSQS-certified surgeons, cases with one ESSQS-certified surgeon as an assistant, cases with one ESSQS-certified surgeon as an adviser, and cases in which an ESSQS-certified surgeon participated partially as an operator were excluded. The Internal Review Board of Hokkaido University Hospital (No. 019-0328) and all participating hospitals approved the study as an exempt human subject study, and informed consent was obtained in an opt-out fashion in accordance with the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare guidelines. The study was registered in the UMIN clinical trials registration system on June 3, 2020 (UMIN 000040645).

The following information was collected from patients' medical records: patient characteristics, clinical features, institutional characteristics, surgical procedures, surgical results, postoperative outcomes, and follow-up data. In terms of the surgical procedure, lateral pelvic node dissection was performed with resection of fat tissue around the common iliac and internal iliac vessels, and around the obturator space, outside the pelvic plexus. The cases were divided into two groups according to surgeon status (a group in which an ESSQS-certified surgeon attended as first surgeon, and a group in which no ESSQS-certified surgeons were involved), and the short-term and middle-term outcomes of the two groups were compared. Short-term outcomes included operative time, blood loss, intraoperative complications (defined as injury to major blood vessels, bowel and other surrounding organs, anastomotic problems, and other intraoperative incidents), conversion rate to open surgery, number of lymph nodes dissected, incidence of all postoperative complications, postoperative bleeding, anastomotic bleeding, anastomotic leakage, intraperitoneal abscesses, and wound infection, bowel obstruction, other postoperative complications, reoperation rate, and postoperative hospital stay were analyzed. Postoperative complications were assessed according to the Clavien–Dindo classification.8 Postoperative complications and reoperations were defined as those occurring within 30 days after surgery. Follow-up was performed at day clinic visits.

For middle-term outcomes, overall survival was defined as the time from surgery to the last visit or death. Recurrence-free survival was defined as the period from surgery to recurrence or any cause of death, and patients who were alive at the end of the follow-up period were censored. Cumulative local recurrence was defined as the period from surgery to local recurrence, and patients with no local recurrence at the end of the follow-up period were censored at death or alive. Three-y overall survival, recurrence-free survival, and cumulative local recurrence-free survival were compared. In addition, the relationship between local recurrence and surgery by ESSQS-certified surgeons was examined in clinical Stage II and III rectal cancers.

The primary endpoint of the study was the open conversion rate. Operative time, blood loss, R0 resection, stage-specific overall survival, recurrence-free survival, and cumulative local recurrence were assessed as secondary endpoints. A patient flow diagram is shown in Figure 1.

2.1 Statistical analysis

All continuous data are reported as means and standard deviations. For cases with surgery performed by an ESSQS-qualified surgeon as a single operator and cases without an ESSQS-qualified surgeon, all statistical tests were performed using a significance level of 0.05 (two-sided). Student's t-tests and χ2tests were used for each category of data and for normally distributed continuous data. Propensity score matching was used to minimize selection bias when comparing the impact of ESSQS-qualified surgeons on postoperative complication rates and other short-term and middle-term outcomes. The following factors were selected for propensity score matching: age, sex, body mass index (BMI), American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) class, bowel obstruction, cT, cN, clinical stage, tumor location, preoperative treatment, operative procedure, combined resection of surrounding organs, lymph node dissection (defined as D3 for high ligation of the inferior mesenteric artery [IMA], D1 for dissection of the marginal artery, and D2 for dissection in between), lateral pelvic node dissection, mobilization of the splenic flexure, diverting stoma, and type and size of institution. These factors were selected because of their potential impact on both surgical outcomes and whether ESSQS-qualified surgeons participated in the procedures. Propensity scores were generated using logistic regression analysis, and all collected covariates were included in the regression model. The multiplicity of tests was not considered. Kaplan–Meier methods were used to prepare survival curves of eligible cases, and they were compared with the log-rank test with a two-sided alpha level of 0.05. Stage 4 cases were excluded in the analysis of the relationship between ESSQS-qualified surgeons and cumulative local recurrence rate, recurrence-free survival, and overall survival. All statistical analyses were performed using JMP Pro v. 16.0.0 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA) and R (R Core Team, 2021, Vienna, Austria).

3 RESULTS

Overall, 3197 laparoscopic rectal resections were performed, of which one concurrent cancer, six cases of multiple intraperitoneal operations, 13 cases of total pelvic exenteration, and two other cases were excluded; 1015 operations were performed with an ESSQS-certified surgeon attending as sole operator, and 544 operations were performed without any ESSQ-certified surgeon involved. Patient characteristics of the ESSQS and non-ESSQS groups prematching are shown in Table 1. The mean age of the prematching ESSQS and non-ESSQS groups was 63.1 and 65.9 years, respectively, with no difference in sex distribution. In the ESSQS group, preoperative comorbidities of ASA Class 3 or higher were less frequent, and a higher proportion of high-volume centers performed more than 100 rectal cancer operations per year. The distribution of tumor location differed between the two groups. The distributions of clinical stage and T stage were similar between the two groups, but the distribution of N stage was different. The profile of preoperative treatment and surgical procedures also differed between the two groups, with high ligation of the IMA, mobilization of the splenic flexure, lateral pelvic node dissection, and diverting stoma more frequent in the ESSQS group (Table 1). After matching, there were 455 cases in both groups, and there were no significant differences between the two groups in patient characteristics, facility characteristics, tumor location, clinical stage, preoperative treatment, or surgical method.

| Prematching | p-value | Postmatching | p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| With ESSQS (n = 1015) | Without ESSQS (n = 544) | With ESSQS (n = 455) | Without ESSQS (n = 455) | |||

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 63.1 (12.3) | 65.9 (11.9) | < 0.0001 | 66.2 (11.1) | 65.5 (12.1) | 0.36 |

| Sex (M:F) | 655:360 | 337:207 | 0.31 | 294:161 | 284:171 | 0.49 |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean (SD) | 22.6 (3.4) | 22.6 (3.7) | 0.83 | 22.6 (3.4) | 22.6 (3.7) | 0.99 |

| ASA class 3 or 4a | 64 (6.3) | 52 (9.6) | 0.0084 | 45 (9.9) | 42 (9.2) | 0.82 |

| Obstruction | 49 (4.8) | 28 (5.2) | 0.71 | 24 (5.3) | 19 (4.2) | 0.43 |

| Institution (volume) | < 0.0001 | 0.14 | ||||

| Cases >100 | 442 (43.5) | 67 (12.3) | 52 (11.4) | 67 (14.7) | ||

| Cases <100 | 573 (56.5) | 477 (87.7) | 403 (88.6) | 388 (85.3) | ||

| Institution (academic) | 0.58 | 0.07 | ||||

| Medical school | 365 (36.0) | 188 (34.6) | 206 (45.3) | 179 (39.3) | ||

| Other | 656 (64.0) | 356 (65.4) | 249 (54.7) | 276 (60.7) | ||

| Location | < 0.0001 | 0.31 | ||||

| RS | 236 (23.3) | 197 (36.2) | 137 (30.1) | 157 (34.5) | ||

| Ra | 324 (31.9) | 196 (36.0) | 160 (35.2) | 141 (31.0) | ||

| Rb | 455 (44.8) | 151 (27.8) | 158 (34.7) | 157 (34.5) | ||

| Clinical T stage | < 0.0001 | 0.89 | ||||

| 1 | 10 (1.0) | 2 (0.4) | 2 (0.4) | 2 (0.4) | ||

| 2 | 39 (3.8) | 26 (4.8) | 25 (5.5) | 25 (5.5) | ||

| 3 | 756 (74.5) | 388 (71.3) | 342 (75.2) | 338 (74.3) | ||

| 4a | 138 (13.6) | 112 (20.6) | 77 (16.9) | 76 (16.7) | ||

| 4b | 72 (7.1) | 16 (2.9) | 9 (2.0) | 14 (3.1) | ||

| Clinical N stage | 0.01 | 0.69 | ||||

| 0 | 467 (46.0) | 260 (47.8) | 207 (45.5) | 222 (48.8) | ||

| 1 | 354 (34.9) | 193 (35.5) | 161 (35.4) | 158 (34.7) | ||

| 2 | 112 (11.0) | 70 (12.9) | 62 (13.6) | 54 (11.9) | ||

| 3 | 82 (8.1) | 21 (3.9) | 25 (5.5) | 21 (4.6) | ||

| Clinical stage | 0.50 | 0.48 | ||||

| II | 467 (46.0) | 260 (47.8) | 207 (45.5) | 222 (48.8) | ||

| IIIA | 354 (34.9) | 193 (35.5) | 161 (35.4) | 158 (34.7) | ||

| IIIB | 194 (19.1) | 91 (16.7) | 87 (19.1) | 75 (16.5) | ||

| Preoperative therapy | < 0.0001 | 0.66 | ||||

| None | 723 (71.2) | 461 (84.7) | 371 (81.5) | 378 (83.1) | ||

| Chemotherapy | 109 (10.7) | 24 (4.4) | 28 (6.2) | 24 (5.3) | ||

| Chemoradiotherapy | 140 (13.8) | 47 (8.6) | 41 (9.0) | 41 (9.0) | ||

| TNT | 42 (4.1) | 11 (2.0) | 15 (3.3) | 11 (2.4) | ||

| Procedures | < 0.0001 | 0.96 | ||||

| HAR | 127 (12.5) | 116 (21.3) | 86 (18.9) | 93 (20.4) | ||

| LAR | 601 (59.2) | 322 (59.2) | 274 (60.2) | 266 (58.5) | ||

| APR | 154 (15.2) | 57 (10.5) | 51 (11.2) | 52 (11.4) | ||

| Hartmann's | 31 (3.1) | 24 (4.4) | 17 (3.7) | 19 (4.2) | ||

| ISR | 101 (10.0) | 25 (4.6) | 27 (5.9) | 25 (5.5) | ||

| Other | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Combined resection | 53 (5.2) | 18 (3.3) | 0.08 | 14 (3.1) | 16 (3.5) | 0.71 |

| High ligation of the IMAa | 789 (77.7) | 313 (57.5) | < 0.0001 | 294 (64.6) | 283 (62.2) | 0.45 |

| Mobilization of SFa | 149 (14.7) | 13 (2.4) | < 0.0001 | 9 (2.0) | 13 (2.9) | 0.65 |

| LND | 0.65 | 0.99 | ||||

| D0/1 | 4 (0.4) | 2 (0.4) | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) | ||

| D2 | 80 (7.9) | 40 (7.4) | 39 (8.6) | 38 (8.4) | ||

| D3 | 931 (91.7) | 502 (92.3) | 415 (91.2) | 16 (3.5) | ||

| LPND | < 0.0001 | 0.66 | ||||

| None | 765 (75.4) | 500 (91.9) | 403 (88.6) | 411 (90.3) | ||

| Unilateral | 74 (7.3) | 19 (3.5) | 24 (5.3) | 19 (4.2) | ||

| Bilateral | 176 (17.3) | 25 (4.6) | 28 (6.2) | 25 (5.5) | ||

| Diverting stoma | 422 (41.6) | 146 (26.8) | < 0.0001 | 148 (32.5) | 132 (29.0) | 0.25 |

- Note: The following factors were selected for propensity score matching: age, sex, body mass index (BMI), American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) class, bowel obstruction, cT, cN, clinical stage, tumor location, preoperative treatment, operative procedure, combined resection of surrounding organs, lymph node dissection (defined as D3 for high ligation of the inferior mesenteric artery (IMA), D1 for dissection of the marginal artery, and D2 for dissection in between, lateral pelvic node dissection, mobilization of the splenic flexure, diverting stoma, and type and size of institution. These factors were selected because of their potential impact on both surgical outcomes and whether ESSQS-qualified surgeons participated in the procedures. Values in parentheses are percentages unless indicated otherwise; Continuous data are described as mean (standard deviation) values.

- Abbreviations: APR, abdominoperineal resection; ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists Physical Status Classification; BMI, body mass index; ESSQS, Endoscopic Surgical Skill Qualification System; HAR, high anterior resection; IMA, inferior mesenteric artery; ISR, intersphincteric resection; LAR, low anterior resection; LND, lymph node dissection; LPND, lateral pelvic node dissection; SD, standard deviation; SF, splenic flexure; TNT, total neoadjuvant therapy; TPE, total pelvic exenteration.

- a The values include missing data.

3.1 Short-term results

After matching, there were no significant differences in the overall rates of postoperative complications of Clavien–Dindo classification grade 3 or higher between the ESSQS and non-ESSQS groups. The ESSQS group had a significantly shorter operative time (286 min vs. 313 min, p < 0.001) and a significantly lower rate of conversion to laparotomy (0.2% vs. 4.2%, p < 0.001). The number of lymph nodes dissected was also significantly higher in the ESSQS group (20.7 vs 18.4, p < 0.002). (Table 2).

| With ESSQS (n = 455) | Without ESSQS (n = 455) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Operative time (min), mean (SD) | 286 (108) | 313 (124) | < 0.001 |

| Blood loss (mL), mean (SD) | 102 (256) | 106 (240) | 0.79 |

| Conversion | 1 (0.2) | 19 (4.2) | < 0.001 |

| Intraoperative complication | 7 (1.5) | 10 (2.2) | 0.46 |

| Number of harvested lymph nodes, mean (SD) | 20.7 (10.8) | 18.4 (11.2) | 0.002 |

| Pathological R0 resection | 446 (98.0) | 441 (96.9) | 0.5 |

| Reoperation | 25 (5.5) | 24 (5.3) | 0.88 |

| Postoperative hospital stay (d) | 17.6 (18.2) | 18.1 (14.2) | 0.66 |

| Postoperative complication (G3) | 63 (13.8) | 68 (14.9) | 0.77 |

| Intraperitoneal bleeding (G3) | 1 (0.2) | 5 (1.1) | 0.08 |

| Anastomotic bleeding (G3) | 2 (0.4) | 2 (0.4) | 1 |

| Anastomotic leakage (G3) | 33 (7.3) | 29 (6.4) | 0.59 |

| Intraperitoneal abscess (G3) | 7 (1.5) | 12 (2.6) | 0.24 |

| Wound infection (G3) | 6 (1.3) | 9 (2.0) | 0.43 |

| Bowel obstruction (G3) | 9 (2.0) | 13 (2.9) | 0.38 |

| Other postoperative complications (G3) | 13 (2.9) | 7 (1.5) | 0.17 |

- Note: Values in parentheses are percentages unless indicated otherwise; Continuous data are described as mean (standard deviation) values.

- Abbreviations: ESSQS, Endoscopic Surgical Skill Qualification System; G3, grade 3 according to the Clavien–Dindo classification system; SD, standard deviation.

3.2 Histopathological results and prognosis

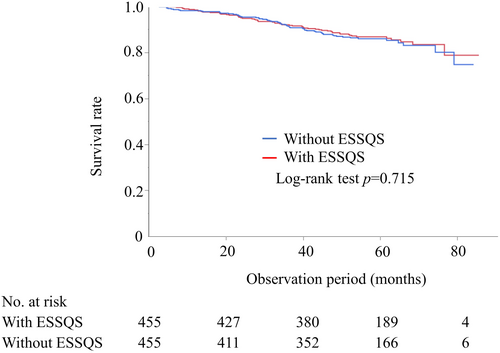

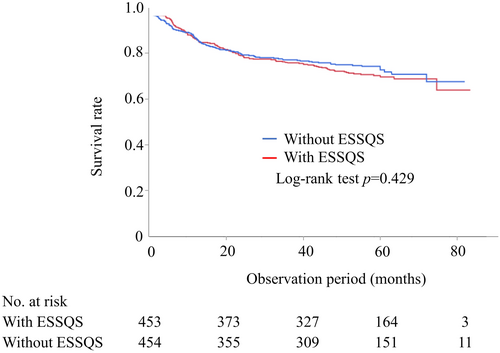

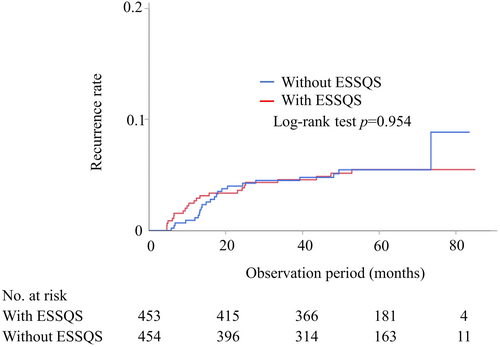

Postoperative histopathological examination showed that there were 170 (37.4%) and 162 (35.6%) Stage II and 220 (48.4%) and 227 (49.9%) Stage III cases in the ESSQS and non-ESSQS groups, respectively. There were no significant differences between the two groups in pathological T-factors, N-factors, pathological stage, tumor size, lymph vascular invasion, vascular invasion, or percentage of undifferentiated cancer. Postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy was administered to 42.9% of the ESSQS group and 44.8% of the non-ESSQS group (Table 3). The median observation period was 58.2 mo in the ESSQS group and 56.7 mo in the non-ESSQS group. The 3-y overall survival rate was 92% in the ESSQS group and 91.5% in the non-ESSQS group (Figure 2). The 3-y overall survival rate for Stage II rectal cancer in the present study was 94.4% in the ESSQS group and 93.3% in the non-ESSQS group, and the disease-free survival rate was 81.7% in the ESSQS group and 83.1% in the non-ESSQS group. For Stage III, the 3-y overall survival rate was 89.6% in the ESSQS group and 89.3% in the non-ESSQS group, and the disease-free survival rate was 75.3% in the ESSQS group and 75.6% in the non-ESSQS group. The 3-y recurrence-free survival rate was 78.4% in the ESSQS group and 79.2% in the non-ESSQS group (Figure 3). The 3-y cumulative local recurrence rate was 4.57% in the ESSQS group and 4.51% in the non-ESSQS group (Figure 4).

| With ESSQS (n = 455) | Without ESSQS (n = 455) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pathological T factor | 0.39 | ||

| 1 | 13 (2.9) | 16 (3.5) | |

| 2 | 67 (14.7) | 80 (17.6) | |

| 3 | 310 (68.1) | 292 (64.2) | |

| 4a | 46 (10.1) | 43 (9.5) | |

| 4b | 8 (1.8) | 16 (3.5) | |

| pCR | 11 (2.4) | 8 (1.8) | |

| Pathological N factor | 0.59 | ||

| 0 | 223 (49.0) | 227 (49.9) | |

| 1 | 145 (31.9) | 162 (35.6) | |

| 2 | 63 (13.8) | 53 (11.6) | |

| 3 | 14 (3.1) | 13 (2.9) | |

| Pathological stage | 0.72 | ||

| I | 52 (11.4) | 57 (12.5) | |

| II | 170 (37.4) | 162 (35.6) | |

| III | 220 (48.4) | 227 (49.9) | |

| IV | 2 (0.4) | 1 (0.2) | |

| pCR | 11 (2.4) | 8 (1.8) | |

| Tumor size (mm), mean (SD) | 45.0 (18.4) | 44.4 (17.7) | 0.62 |

| Lymph vascular invasiona | 222 (48.8) | 272 (59.8) | 0.79 |

| Venous invasiona | 325 (71.4) | 303 (66.6) | 0.2 |

| Undifferentiated adenocarcinomaa | 17 (3.7) | 15 (3.3) | 0.1 |

| Adjuvant chemotherapya | 195 (42.9) | 204 (44.8) | 0.11 |

- Note: Values in parentheses are percentages unless indicated otherwise.

- Abbreviation: ESSQS, endoscopic surgical skill qualification system.

- a The values include missing data.

4 DISCUSSION

To the best of our knowledge, this is the largest multicenter study comparing surgical outcomes with and without ESSQS-certified surgeons as operators. ESSQS-certified surgeons were superior to noncertified surgeons as operators, with shorter operative time, a lower laparotomy conversion rate, and a higher number of lymph nodes dissected. Several previous studies with small numbers have reported that operations performed by ESSQS-certified surgeons have a shorter operative time and a lower rate of laparotomy conversion.9, 10 The results of the current study have confirmed them in a large-scale multicentric study. Especially, the conversion rate was 0.2% in the ESSQS group in the present study, whereas the conversion rates to laparotomy in previous large RCTs for rectal cancer ranged from 9% to 16%,11-13 reflecting the stable skills of ESSQS-certified surgeons. A previous study based on the National Clinical Database (NCD) under similar conditions reported no difference in complication rates whether or not the procedure was performed by an ESSQS-certified surgeon, but differences in operative time and blood loss were seen.10 The present study differs from that study based on the NCD in the definition of ESSQS-certified surgeon nonparticipation. The study based on the NCD compared ESSQS-certified surgeons with surgeons without ESSQS certification as operators, but included in the non-ESSQS group cases in which a certified surgeon attended as an assistant or adviser. In the present study, to evaluate the skills of ESSQ-certified surgeons as operators, cases in which an ESSQ-certified surgeon attended as an assistant or adviser were excluded, and cases in which an ESSQS-certified surgeon attended as the sole operator and cases in which no ESSQS-certified surgeons attended the operation were compared. The surgeons certified in other specialties were not included in the non-ESSQS group. There are also differences in the uniformity of surgical quality. The present study collected data from institutions belonging to the JSLCS, a research organization specializing in laparoscopic colorectal surgery, so it can be assumed that the quality of surgery was almost entirely uniform across the centers in the present study. The JSLCS is considered to have achieved one of the objectives of the ESSQS system―standardization of surgical techniques. Therefore, we believe that the assessment of surgical competence based on data collected from centers belonging to the JSLCS reflects the technical relevance of the ESSQS certification system. Although the present study did not collect data to assess the experience of surgeons in the non-ESSQS group, as this study was conducted at JCLCS-participating institutions, a certain level of quality was ensured even for surgeries performed by non-ESSQS certified surgeons. The postoperative complication rates for the ESSQS and non-ESSQS groups were 13.8% and 14.9%, respectively, which were better than previously reported results from clinical trials (21%–40%), and thus a clear difference was absent.11, 14, 15 Furthermore, some cases in which preoperative treatment or lateral pelvic node dissection was performed were excluded from the analysis due to matching. Some of these highly challenging cases were excluded after matching, and it is possible that differences in the technical impact on highly challenging cases may not have been reflected in the results. This is the first report on stage-specific prognosis of surgery by ESSQS-certified physicians in a large-scale study. The results of the survival in both the ESSQS and non-ESSQS group compares favorably with previous clinical trials, which may be the reason there was no difference in prognosis between the two groups.15, 16 According to a report by the Japan Society for Endoscopic Surgery (JSES), laparoscopic surgery for rectal cancer accounted for 65.8% during the study period, and laparoscopic surgery for advanced rectal cancer was a common procedure in many centers.17 Considering that most laparoscopic surgeries for rectal cancer in Japan had already been standardized and commonly performed, and that the quality of surgery as a whole had reached a sufficient level, this result was expected.

The present study has several limitations. The first is that this was a retrospective cohort study. Propensity score matching was performed to minimize selection bias, but confounding differences may still exist. The present study showed clinically meaningful results for the short-term outcomes described in the protocol, but the multiplicity of the tests was not considered. Second, the difficulty of rectal surgery was only examined in terms of surgical procedure. The difficulty of rectal cancer surgery depends on patient obesity, tumor size and location, preoperative treatment, and lateral pelvic node dissection18 However, the present study did not stratify difficulty according to these factors. In the present study the types of the procedure were balanced but the procedures were not limited to some specific one. Additional analysis might be needed limited to low anterior resection or abdominoperineal resection, although another subanalysis showed that attending an ESSQS-certified surgeon as an operator, an assistant or an advisor significantly improved short-term outcomes for low anterior resection.19 Third, there was a difference in the number of cases between the two groups. The institutions involved in the study belonged to the JSLCS, and 80% of the enrolled cases were attended by ESSQS-certified surgeons in the role of operator, assistant, or external adviser. In addition, the specialty of ESSQS-certified surgeons was not specified, so surgeons certified in other specialties were included in the ESSQS group. Yamaguchi et al. had reported that operative mortality after laparoscopic low anterior resection for rectal cancer was significantly higher in the biliary-certified group than in the colorectal-certified group.20 Moreover, anastomotic leakage was significantly lower in the colorectal-certified group than in the stomach-certified and noncertified groups.20 Therefore, not limiting the area of certification could have affected the results. Consequently, the number of cases in the non-ESSQS group was small compared to that in the ESSQS group, which may have introduced bias. Less than 10% of surgeons in Japan are ESSQS-certified, and thus the results of our analysis of institutions where this ratio was much higher may not be generalizable to the general circumstances in Japan. However, the present study was designed purely to compare the impact of an ESSQS-certified surgeon as an operator and we believe the results are meaningful. For local recurrence, the low number of events may have impacted the results. Extending the observation period or increasing the number of cases may provide more definitive results. Another weakness is that the potential impact of the presence of ESSQS-certified surgeons at the studied institutions has not been eliminated. Most of the institutions belonging to the JSLCS have an established system for safe practice and education in laparoscopic colorectal by ESSQS-certified surgeons. Therefore, even in the non-ESSQS group, ESSQ-certified surgeons may have had an indirect influence both preoperatively and postoperatively. Additionally, it is possible that institutions with more ESSQS-certified surgeons may provide more efficient and effective training to their trainees, which may have better surgical outcomes.

The present study showed the usefulness of ESSQS-certified surgeons as operators in the performance of laparoscopic surgery for advanced rectal cancer. Taken together with previous reports that showed the lower incidence of severe morbidities of Clavien–Dindo grade ≥ IIIa (8.0% vs. 13.3%, p = 0.016) after the procedures with ESSQS-certified supervisor (assistants or advisor),21 the current results indicate that the usefulness of ESSQ-certified surgeons has different implications, depending on their role. The fact that ESSQS certification based on basic skills was associated with shorter operative times and lower conversion rates, even in advanced procedures such as rectal cancer surgery, suggests the usefulness of ESSQS as a training system for developing surgeons with stable skills. On the other hand, these results also suggest that the acquisition of basic techniques is not sufficient to improve complication rates and middle-term prognosis, and that surgeons should strive to further improve their skills. New surgical approaches to rectal cancer, such as robot-assisted surgery, as well as transanal total mesorectal excision, are becoming more mainstream, and these new approaches are highly dependent on the skills of the surgeon themselves. There is no doubt that it is useful and essential for surgeons to master and develop basic surgical skills and perform surgery independently, safely, and effectively, regardless of the approach, and this should be the aim of all surgeons. In this sense, the ESSQS certification should continue to be used.

In conclusion, laparoscopic rectal surgery performed by ESSQS-certified surgeons as operators was associated with improvements in short-term outcomes, and the impact might depend on their role.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Nobuki Ichikawa, Shigenori Homma, and Akinobu Taketomi designed the protocol. Ken Kojo, Takahiro Yamanashi, Manabu Yamamoto, Takuya Miura, Yoshiyuki Ishii, Atsushi Ishibe, and Hiroomi Ogawa contributed to the data collection. Nobuki Ichikawa and Hiroaki Iijima analyzed the data. Ken Kojo drafted the article. Nobuki Ichikawa, Takahiro Yamanashi, Masafumi Inomata, and Takeshi Naitoh contributed to the finalization of the article. All authors read and approved the final version of the article. Author Masafumi Inomata is an editorial board member of Annals of Gastroenterological Surgery.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

EnSSURE study group collaboratives: Akinobu Furutani, Akiyoshi Kanazawa, Akiyoshi Noda, Chikayoshi Tani, Daisuke Yamamoto, Fumihiko Fujita, Fuminori Teraishi, Fumio Ishida, Fumitaka Asahara, Heita Ozawa, Hideaki Karasawa, Hideki Osawa, Hiroaki Nagano, Hiroaki Takeshita, Hirofumi Ota, Hirokazu Suwa, Hiroki Ochiai, Hiroshi Saeki, Hirotoshi Hasegawa, Hiroyuki Bando, Hisanaga Horie, Hisashi Nagahara, Jun Watanabe, Kaori Hayashibara, Kay Uehara, Kazuhiro Takehara, Ken Okamoto, Kenichiro Saito, Koji Ikeda, Koji Munakata, Koki Otsuka, Koki Goto, Koya Hida, Kunihiko Nagakari, Mamoru Uemura, Manabu Shimomura, Manabu Shiozawa, Manabu Takata, Masaaki Ito, Masahiko Watanabe, Masakatsu Numata, Masashi Miguchi, Masatsune Shibutani, Mayumi Ozawa, Mitsuhisa Takatsuki, Naoya Aisu, Naruhiko Sawada, Nobuaki Suzuki, Ryo Ikeshima, Ryo Inada, Ryuichi Oshima, Satoshi Maruyama, Shigehiro Kojima, Shigeki Yamaguchi, Shiki Fujino, Shinichiro Mori, Shinobu Ohnuma, Sho Takeda, Shota Aoyama, Shuji Saito, Shusaku Takahashi, Takahiro Sasaki, Takeru Matsuda, Tatsunari Fukuoka, Tatsunori Ono, Tatsuya Kinjo, Tatsuya Shonaka, Teni Godai, Tohru Funakoshi, Tomohiro Adachi, Tomohiro Yamaguchi, Tomohisa Furuhata, Toshimoto Kimura, Tomonori Akagi, Toshisada Aiba, Toshiya Nagasaki, Toshiyoshi Fujiwara, Tsukasa Shimamura, Tsunekazu Mizushima, Yasuhito Iseki, Yasuo Sumi, Yasushi Rino, Yasuyuki Kamada, Yohei Kurose, Yoshiaki Kita, Yoshihiro Kakeji, Yoshihiro Takashima, Yoshihito Ide, Yoshiharu Sakai, Yoshinori Munemoto, Yoshito Akagi, Yuji Inoue, Yuki Kiyozumi, Yukihito Kokuba, Yukitoshi Todate, Yusuke Suwa, Yusuke Sakimura, Yusuke Shimodaira.

FUNDING INFORMATION

The authors did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors for this research.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflicts of interest for this article.

ETHICS STATEMENT

Approval of the research protocol: The protocol for this research project has been approved by a suitably constituted Ethics Committee of the institution and it conforms to the provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki (amended in October 2013).

Informed Consent: Informed consent was obtained in an opt-out fashion in accordance with the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare guidelines.

Registry and the Registration No. of the study/trial: N/A.

Animal Studies: N/A.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.