Risk factors for incisional hernia according to different wound sites after open hepatectomy using combinations of vertical and horizontal incisions: A multicenter cohort study

Abstract

Background: Although several risk factors for incisional hernia after hepatectomy have been reported, their relationship to different wound sites has not been investigated. Therefore, this study aimed to examine the risk factors for incisional hernia according to various wound sites after hepatectomy.

Methods: Patients from the Osaka Liver Surgery Study Group who underwent open hepatectomy using combinations of vertical and horizontal incisions (J-shaped incision, reversed L-shaped incision, reversed T-shaped incision, Mercedes incision) between January 2012 and December 2015 were included. Incisional hernia was defined as a hernia occurring within 3 y after surgery. Abdominal incisional hernia was classified into midline incisional hernia and transverse incisional hernia. The risk factors for each posthepatectomy incisional hernia type were identified.

Results: A total of 1057 patients met the inclusion criteria. The overall posthepatectomy incisional hernia incidence rate was 5.9% (62 patients). In the multivariate analysis, the presence of diabetes mellitus and albumin levels <3.5 g/dL were identified as independent risk factors. Moreover, incidence rates of midline and transverse incisional hernias were 2.4% (25 patients), and 2.3% (24 patients), respectively. In multivariate analysis, the independent risk factor for transverse incisional hernia was the occurrence of superficial or deep incisional surgical site infection, and interrupted suturing for midline incisional hernia.

Conclusions: Risk factors for incisional hernia after hepatectomy depend on the wound site. To prevent incisional hernia, running suture use might be better for midline wound closure. The prevention of postoperative wound infection is important for transverse wounds, under the presumption of preoperative nutrition and normoglycemia.

1 INTRODUCTION

Incisional hernia is a typical complication of abdominal surgery. Once it occurs, surgery is the only therapy, and patients are exposed not only to cosmetic problems, but also to a risk of death from incarceration. In addition, it causes symptoms, such as abdominal discomfort and pain.1, 2 The results of a questionnaire survey on postoperative wound closure indicated that the interrupted suture was used in ~75% of cases in Japan. The types of sutures included monofilament and braided sutures. Each type was used in ~50% of the cases. However, the fascia and subcutaneous tissue suture methods, as well as subcutaneous drain placement method and dressing materials, vary depending on the institution.3 Meanwhile, running sutures are used in Europe and the United States.4

Abdominal incisional hernia occurrence is considered closely related to the hernia site, suture types, and wound closure methods. In a meta-analysis, the incidence rate of hernia after median incision was higher with fast absorbable sutures than with slowly absorbable sutures (P < .009) and nonabsorbable sutures (P = .001), whereas it was similar between slowly absorbable and nonabsorbable sutures, and between running and interrupted sutures.5 In addition, median incisions have been associated with a higher incidence of hernia at incision sites than horizontal (relative risk = 1.77; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.09–2.87) and paramedian incisions (relative risk = 3.41; 95% CI, 1.02–11.45).6

In reports on hernias occurring after hepatectomies, the risk factors included reverse T incision, refractory ascites, body mass index (BMI), repeated hepatectomy, steroid usage, running suture use, and the 7S domain of type IV collagen value.7, 8 Hernia risk factors following open hepatectomy for metastatic liver cancer included the duration of preoperative chemotherapy and bevacizumab administration.9 However, currently available studies are limited to single institutions and did not elucidate the impact of the hernia site, type of suture material, and wound closure method on the occurrence of incisional hernia after hepatectomy. Moreover, the posthepatectomy wound is a combination of vertical and horizontal wounds with different injured tissues. Therefore, we hypothesized that examining the wounds separately would provide a clue to prevent incisional hernia after hepatectomy. Hence, this multicenter study aimed to investigate in detail the risk factors for abdominal incisional hernia according to different wound sites after hepatectomy.

2 PATIENTS AND METHODS

Data of patients from eight university hospitals in the Kansai region were retrospectively reviewed. Our study group was called the Osaka Liver Surgery Study Group and has been conducting several clinical studies on hepatectomy.

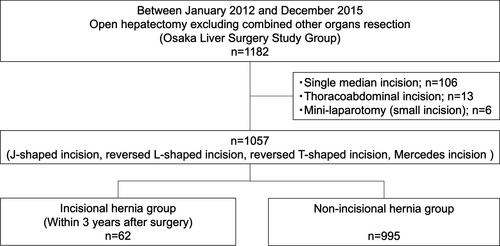

We performed open hepatectomy without biliary tract reconstruction and combined resection of adjacent organs for 1182 patients in eight institutions of the Osaka Liver Surgery Study Group between January 2012 and December 2015. Patients who underwent mini-laparotomy (small incision), single median incision, and thoracoabdominal incision were excluded. Finally, we investigated 1057 patients who underwent open hepatectomy using J-shaped, reversed L-shaped, reversed T-shaped, and Mercedes incisions (Figure 1).

Abdominal incisional hernia was defined as an explicit prolapse of an intra-abdominal organ at the incisional site on clinical examination within 3 y after the operation, and was classified into midline, central, transverse, and right edge categories, based on the hernia occurrence site (Figure 2) Transverse and right edge incisional hernias were further classified as transverse incisional hernias. The risk factors of midline and transverse (transverse and right edge) incisional hernias were investigated. We investigated the following background factors: age; sex; BMI before surgery; presence/absence of anemia; albumin, bilirubin, and creatinine levels; and indocyanine green retention rate at 15 min (ICGR15). Complications before surgery, presence/absence of diabetes mellitus and respiratory diseases, smoking history, steroid usage, and preoperative chemotherapy administration were examined. Anemia was defined as a hemoglobin level ≤13.0 g/dL in men and ≤12.0 g/dL in women. Respiratory diseases included asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and interstitial pneumonia that required regular treatment with oral drugs or inhalants. Smoking history was defined as ≥400 cigarettes = cigarettes per day × number of years. Steroid usage was defined as receiving ≥5 mg/day prednisolone or its equivalent for ≥1 month before surgery. Chemotherapy was defined as the preoperative use of chemotherapeutic agents, including bevacizumab. General physical status was also assessed using the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) classification.10 Surgical factors, operative time, blood loss, need for blood transfusion, operative method, and need for repeat hepatectomy were examined. Operative methods were classified into anatomical resection, such as a subsegmentectomy or more extensive resection, and partial resection. In addition, the effects of using running and interrupted sutures and braided and monofilament sutures in the fascia suture were compared. A late absorbable suture was used in all institutions. The incidences of postoperative complications, including organ/space surgical site infection (SSI) and incisional SSI (superficial or deep), identified according to the Centers for Disease Control guidelines for the classification of SSIs, were analyzed.11, 12 For other complications, the Clavien–Dindo classification was used.13, 14 Refractory ascites was defined as postoperative ascites ≥1 L persisting for 7 d after surgery and requiring abdominal drainage. Based on these factors, the independent risk factors for postoperative transverse and midline incisional hernia were examined by univariate and multivariate analyses.

2.1 Statistical analysis

The cutoff values of the continuous variables were selected using receiver-operating characteristic curve analysis. In addition, we decided on the cutoff values that were close to the most significant difference and clinically useful. For example, a cutoff albumin level of 3.5 g/dL is also used in the Child–Pugh classification. A logistic regression analysis was used for multivariate analysis using factors with P ≤ .1 in the univariate analysis. All statistical analyses were performed using R v. 3.5.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing; https://cran.r-project.org/bin/macosx/).

3 RESULTS

The overall incidence of incisional hernias was 62/1057, with 3.5%, 5.4%, and 5.9% in the first, second, and third years, respectively.

The incisional hernia sites are shown in Figure 2. The most frequent site was the midline (25/62), accounting for 40.3% of all cases, followed by the transverse (15/62, 24.2%), central (13/62, 21.0%), and right edge (9/62, 14.5%) sites.

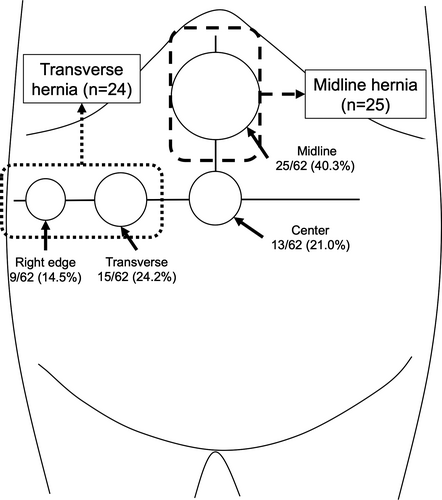

The cumulative incidence rate of each incisional hernia site is shown in Figure 3. The midline site was associated with a significantly higher incidence of incisional hernia compared to the right edge site (P = .006). The comparison among other sites showed no significant difference in the incidence of incisional hernia (Figure 3).

The univariate analysis revealed that the overall incidence of abdominal incisional hernias was significantly higher at ages ≥65 y (incisional hernia group, 80.6% vs nonincisional hernia group, 67.7%; P = .035). Diabetic patients accounted for 38.7% of patients in the incisional hernia group as compared with 24.5% in the nonincisional hernia group (P = .016). No significant differences were demonstrated in sex, BMI (<25 kg/m2 vs ≥25 kg/m2), ASA physical status (<class 3 vs ≥class 3), smoking history, use of steroids, primary disease (hepatocellular carcinoma vs others), preoperative chemotherapy, and repeat hepatectomy. For blood tests, the proportion of patients with albumin levels <3.5 g/dL was significantly greater in the incisional hernia group (incisional hernia group, 30.6% vs nonincisional hernia group, 17.9%; P = .038). No significant differences were found in bilirubin levels (<1.0 mg/dL vs ≥1.0 mg/dL), creatinine levels (<1.0 mg/dL vs ≥1.0 mg/dL), and ICGR15 (<15% vs ≥15%). Among the surgical factors, the operative method (partial vs anatomical), blood loss (<1000 mL vs ≥1000 mL), operative time (<360 min vs ≥360 min), and transfusion were similar between the two groups. No significant differences were found in superficial or deep incisional SSI (incisional hernia group vs nonincisional hernia group: 11.3% vs 5.6%, P = .089), organ/space SSI (9.7% vs 11.1%, P >.999), and other complications (6.5% vs 3.2%). In terms of refractory ascites occurrence, no significant difference was found between the two groups.

We performed a multivariate analysis using factors with P ≤ .1 in the univariate analysis. The results indicated that the presence of diabetes mellitus (risk ratio, 1.74; 95% CI, 1.00–3.00) and albumin levels <3.5 g/dL (risk ratio, 1.82; 95% CI, 1.01–3.03) were independent risk factors of incisional hernia occurrence (Table 1).

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Non-incisional hernia (n = 995) |

Incisional hernia (n = 62) |

P-value | Odds ratio | P-value | ||

| Age | <65 y | 321 (32.3) | 12 (19.4) | .035 | 1.61 (0.83–3.11) | .16 |

| ≥65 y | 674 (67.7) | 50 (80.6) | ||||

| Sex | Men | 707 (71.1) | 47 (75.8) | .472 | ||

| Women | 288 (28.9) | 15 (24.2) | ||||

| Body mass index | <25 kg/m2 | 773 (77.7) | 45 (72.6) | .35 | ||

| ≥25 kg/m2 | 222 (22.3) | 17 (27.4) | ||||

| ASA physical status | <class 3 | 885 (88.9) | 56 (90.3) | >.999 | ||

| ≥class 3 | 110 (11.1) | 6 (9.7) | ||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 244 (24.5) | 24 (38.7) | .016 | 1.74 (1.00–3.00) | .048 | |

| Smoking history | 423 (42.5) | 30 (48.4) | .428 | |||

| Steroid usage | 13 (1.3) | 1 (1.6) | .573 | |||

| Respiratory diseases | 42 (4.2) | 1 (1.6) | .509 | |||

| Primary disease | HCC | 535 (53.8) | 41 (66.1) | .066 | 1.46 (0.83–2.55) | .19 |

| Others | 460 (46.2) | 21 (33.9) | ||||

| Preoperative chemotherapy | 174 (17.5) | 10 (16.1) | .865 | |||

| Repeat hepatectomy | 188 (18.9) | 12 (19.4) | .869 | |||

| Anemia | 481 (48.3) | 31 (50.0) | .896 | |||

| Albumin | <3.5 g/dL | 178 (17.9) | 19 (30.6) | .018 | 1.82 (1.02–3.23) | .041 |

| ≥3.5 g/dL | 817 (82.1) | 43 (69.4) | ||||

| Total bilirubin | <1.0 mg/dL | 809 (81.3) | 48 (77.4) | .503 | ||

| ≥1.0 mg/dL | 186 (18.7) | 14 (22.6) | ||||

| Creatinine | <1.0 mg/dL | 836 (84.0) | 55 (88.7) | .374 | ||

| ≥1.0 mg/dL | 159 (16.0) | 7 (11.3) | ||||

| ICGR15 | <15% | 657 (66.0) | 40 (64.5) | .784 | ||

| ≥15% | 338 (34.0) | 22 (35.5) | ||||

| Operative method | Partial | 371 (37.3) | 18 (29.0) | .222 | ||

| Anatomic | 624 (62.7) | 44 (71.0) | ||||

| Blood loss | <1000 mL | 686 (68.9) | 44 (71.0) | .779 | ||

| ≥1000 mL | 309 (31.1) | 18 (29.0) | ||||

| Operative time | <360 min | 593 (59.6) | 37 (59.7) | .655 | ||

| ≥360 min | 402 (40.4) | 25 (40.3) | ||||

| Transfusion | 254 (25.5) | 14 (22.6) | .086 | |||

| Superficial or deep incisional SSI | 56 (5.6) | 7 (11.3) | .089 | 2.13 (0.91–4.96) | .081 | |

| Organ/space SSI | 110 (11.1) | 6 (9.7) | >.999 | |||

| Other complications (≥Clavien–Dindo grade III) | 32 (3.2) | 4 (6.5) | .155 | |||

| Refractory ascites | 65 (6.5) | 5 (8.1) | .597 | |||

- Abbreviations: ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists; ICGR15, indocyanine green retention rate at 15 min; SSI, surgical site infection.

Based on the structure of the fascia under the incision site, we defined hernias in the midline site as midline incisional hernias (n = 25) and hernias in the transverse and right edge sites as transverse incisional hernias (n = 24; Figure 2). The wound crossing area of the central site was excluded from the investigation.

First, the risk factors for transverse incisional hernia were investigated. In the univariate analysis, the transverse incisional hernia group had a significantly higher proportion of elderly patients (≥65 y) and those with high ICGR15 values (≥15%). Moreover, 16.7% and 5.7% of patients in the transverse incisional hernia and nontransverse incisional hernia groups, respectively, had postoperative superficial or deep incisional SSI (P = .049). We assessed the types of suture and closing methods used in the posterior and anterior fascia. For the posterior fascia, the use of interrupted and running sutures was similar between the transverse incisional hernia and nontransverse incisional hernia groups. Meanwhile, the rate of closing with monofilament suture was higher than that with braided suture in the transverse incisional hernia group (P = .094).

Factors with P ≤ .1 were included in the multivariate analysis. As a result, the independent risk factor for transverse incisional hernia was the occurrence of superficial or deep incisional SSI (risk ratio, 4.00; 95% CI, 1.27–12.60; Table 2).

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-transverse incisional hernia (n = 1033) | Transverse incisional hernia (n = 24) | P-value | Odds ratio | P-value | ||

| Age | <65 y | 330 (31.9) | 3 (12.5) | .046 | 2.41 (0.69–8.38) | .17 |

| ≥65 y | 703 (68.1) | 21 (87.5) | ||||

| Sex | Men | 736 (71.2) | 18 (75.0) | .821 | ||

| Women | 297 (28.8) | 6 (25.0) | ||||

| Body mass index | <25 kg/m2 | 803 (77.7) | 15 (62.5) | .086 | 1.93 (0.81–4.62) | .14 |

| ≥25 kg/m2 | 230 (22.3) | 9 (37.5) | ||||

| ASA physical status | <class 3 | 921 (89.2) | 20 (83.3) | .324 | ||

| ≥class 3 | 112 (10.8) | 4 (16.7) | ||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 258 (25.0) | 10 (41.7) | .093 | 1.60 (0.68–3.77) | .28 | |

| Smoking history | 439 (42.5) | 14 (58.3) | .145 | |||

| Steroid usage | 13 (1.3) | 1 (4.2) | .276 | |||

| Respiratory diseases | 43 (4.2) | 0 (0.0) | .62 | |||

| Primary disease | HCC | 558 (54.0) | 18 (75.0) | .06 | 1.88 (0.71–4.99) | .2 |

| Others | 475 (46.0) | 6 (25.0) | ||||

| Preoperative chemotherapy | 179 (17.3) | 5 (20.8) | .592 | |||

| Repeat hepatectomy | 195 (18.9) | 5 (20.8) | .793 | |||

| Anemia | 502 (48.6) | 10 (41.7) | .541 | |||

| Albumin | <3.5 g/dL | 189 (18.3) | 8 (33.3) | .105 | ||

| ≥3.5 g/dL | 844 (81.7) | 16 (66.7) | ||||

| Total bilirubin | <1.0 mg/dL | 840 (81.3) | 17 (70.8) | .192 | ||

| ≥1.0 mg/dL | 193 (18.7) | 7 (29.2) | ||||

| Creatinine | <1.0 mg/dL | 868 (84.0) | 23 (95.8) | .156 | ||

| ≥1.0 mg/dL | 165 (16.0) | 1 (4.2) | ||||

| ICGR15 | <15% | 686 (66.4) | 11 (45.8) | .048 | 1.74 (0.75–4.05) | .2 |

| ≥15% | 347 (33.6) | 13 (54.2) | ||||

| Operative method | Partial | 383 (37.1) | 6 (25.0) | .286 | ||

| Anatomic | 650 (62.9) | 18 (75.0) | ||||

| Blood loss | <1000 mL | 712 (68.9) | 18 (75.0) | .657 | ||

| ≥1000 mL | 321 (31.1) | 6 (25.0) | ||||

| Operative time | <360 min | 619 (59.9) | 11 (45.8) | .207 | ||

| ≥360 min | 414 (40.1) | 13 (54.2) | ||||

| Transfusion | 265 (25.7) | 3 (12.5) | .162 | |||

| Posterior fascia suture type | Monofilament | 585 (56.6) | 18 (75.0) | .094 | 0.47 (0.18–1.21) | .12 |

| Braid | 448 (43.4) | 6 (25.0) | ||||

| Posterior fascia closure method | Interrupted | 513 (49.7) | 8 (33.3) | .148 | ||

| Running | 520 (50.3) | 16 (66.7) | ||||

| Anterior fascia suture type | Monofilament | 583 (56.4) | 10 (41.7) | .211 | ||

| Braid | 450 (43.6) | 14 (58.3) | ||||

| Anterior fascia closure method | Interrupted | 662 (64.1) | 19 (79.2) | .194 | ||

| Running | 370 (35.9) | 5 (20.8) | ||||

| Superficial or deep incisional SSI | 59 (5.7) | 4 (16.7) | .049 | 4.00 (1.27–12.6) | .018 | |

| Organ/space SSI | 112 (10.8) | 4 (16.7) | .324 | |||

| Other complications (≥Clavien–Dindo grade III) | 35 (3.4) | 1 (4.2) | .569 | |||

| Refractory ascites | 68 (6.6) | 2 (8.3) | .67 | |||

- Abbreviations: ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists; ICGR15, indocyanine green retention rate at 15 min; SSI, surgical site infection.

Thereafter, the risk factors for midline incisional hernia were assessed. Univariate and multivariate analyses revealed that the incidence of midline incisional hernia was significantly higher only in patients whose wounds were closed with interrupted sutures (midline incisional hernia group vs nonmidline incisional hernia group, 68.2% vs 88.0%; P = .047) with risk ratio of 0.29 (95% CI, 0.09–0.93; Table 3).

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Non-midline incisional hernia (n = 1032) |

Midline incisional hernia (n = 25) |

P-value | Odds ratio | P-value | ||

| Age | <65 y | 329 (31.9) | 4 (16.0) | .126 | ||

| ≥65 y | 703 (68.1) | 21 (84.0) | ||||

| Sex | Men | 734 (71.1) | 20 (80.0) | .381 | ||

| Women | 298 (28.9) | 5 (20.0) | ||||

| Body mass index | <25 kg/m2 | 798 (77.3) | 20 (80.0) | >.999 | ||

| ≥25 kg/m2 | 234 (22.7) | 5 (20.0) | ||||

| ASA physical status | <class 3 | 918 (89.0) | 23 (92.0) | >.999 | ||

| ≥class 3 | 114 (11.0) | 2 (8.0) | ||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 261 (25.3) | 7 (28.0) | .816 | |||

| Smoking history | 439 (42.5) | 14 (56.0) | .22 | |||

| Steroid usage | 14 (1.4) | 0 (0.0) | >.999 | |||

| Respiratory diseases | 43 (4.2) | 0 (0.0) | .62 | |||

| Primary disease | HCC | 562 (54.5) | 14 (56.0) | >.999 | ||

| Others | 470 (45.5) | 11 (44.0) | ||||

| Preoperative chemotherapy | 182 (17.6) | 2 (8.0) | .289 | |||

| Repeat hepatectomy | 195 (18.9) | 5 (20.0) | .8 | |||

| Anemia | 498 (48.3) | 14 (56.0) | .545 | |||

| Albumin | <3.5 g/dL | 191 (18.5) | 6 (24.0) | .443 | ||

| ≥3.5 g/dL | 841 (81.5) | 19 (76.0) | ||||

| Total bilirubin | <1.0 mg/dL | 838 (81.2) | 19 (76.0) | .449 | ||

| ≥1.0 mg/dL | 194 (18.8) | 6 (24.0) | ||||

| Creatinine | <1.0 mg/dL | 871 (84.4) | 20 (80.0) | .575 | ||

| ≥1.0 mg/dL | 161 (15.6) | 5 (20.0) | ||||

| ICGR15 | <15% | 678 (65.7) | 19 (76.0) | .393 | ||

| ≥15% | 354 (34.3) | 6 (24.0) | ||||

| Operative method | Partial | 381 (36.9) | 8 (32.0) | .68 | ||

| Anatomic | 651 (63.1) | 17 (68.0) | ||||

| Blood loss | <1000 mL | 712 (69.0) | 18 (72.0) | .83 | ||

| ≥1000 mL | 320 (31.0) | 7 (28.0) | ||||

| Operative time | <360 min | 611 (59.2) | 19 (76.0) | .102 | ||

| ≥360 min | 421 (40.8) | 6 (24.0) | ||||

| Transfusion | 262 (25.4) | 6 (24.0) | >.999 | |||

| Fascia suture type | Monofilament | 584 (56.6) | 18 (72.0) | .153 | ||

| Braid | 448 (43.4) | 7 (28.0) | ||||

| Fascia closure method | Interrupted | 704 (68.2) | 22 (88.0) | .047 | 0.29 (0.09–0.99) | 0.047 |

| Running | 328 (31.8) | 3 (12.0) | ||||

| Superficial or deep incisional SSI | 60 (5.8) | 3 (12.0) | .183 | |||

| Organ/space SSI | 115 (11.1) | 1 (4.0) | .511 | |||

| Other complications (≥Clavien–Dindo grade III) | 34 (3.3) | 2 (8.0) | .208 | |||

| Refractory ascites | 68 (6.6) | 2 (8.0) | .679 | |||

- Abbreviations: ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists; ICGR15, indocyanine green retention rate at 15 min; SSI, surgical site infection.

4 DISCUSSION

This multicenter study clearly showed that the risk factors of all kinds of abdominal incisional hernias after open hepatectomy were low albumin levels and diabetes mellitus history, as these impart a low wound-healing ability. Interestingly, the risk factors for abdominal incisional hernias differed according to the wound site, with wound infection primarily contributing to the development of transverse incisional hernias, and interrupted suture use being the most important factor in the development of midline abdominal incisional hernias.

Incisional hernia is a typical complication of abdominal surgery; many studies have been hitherto published regarding this topic. In their meta-analysis, Kossler et al reported incidence rates of abdominal incisional hernia of 10.1% and 4.5% in open and laparoscopic surgeries, respectively.15 Based on the operative method, the frequencies of incisional hernia after open colorectal surgery, bariatric surgery, and liver transplantation are reported to be 7.8–10%16-18, 4–10% 19, and 6–15.1%,20, 21 respectively. These surgical operations have high risks for incisional hernias, due to contamination by intestinal bacteria in colorectal surgery, high intra-abdominal pressure in bariatric surgery, and immunosuppressive drug administration in liver transplantation. Our results demonstrated that the incidence of incisional hernia after open hepatectomy was 5.9%. Therefore, incisional hernia occurrence rate after open hepatectomy is lower than that after high-risk surgery; however, it is slightly higher than that after normal aseptic surgery.

Many patients developed abdominal incisional hernia within 6 mo to 3 y after surgery; the frequency was higher, especially when a midline incision was used. The risk factors of abdominal incisional hernia vary widely and can be classified as cytotoxic factors, such as SSI and inflammation of the wound site; external factors, such as obesity, ascites, and ileus; and healing factors, such as blood flow, nutritional disorder, and steroid use.22-27

In the comparison of the impact of suture types on the occurrence of abdominal incisional hernia, several meta-analyses found similar incidences for absorbable and nonabsorbable sutures. However, it was reported that the incidence of abdominal incisional hernia was higher for fast absorbable sutures than for slowly absorbable sutures.28, 29 Therefore, slowly absorbable sutures are currently the most commonly used sutures for wound closure. For suturing, small bites <10 mm from the wound edges have been recommended, and a suture length-to-wound length ratio of 4:1 is considered safe and applicable.30 Compared with braided sutures, monofilament sutures are noncapillary and do not spread bacteria, which is favorable for infection prevention. Therefore, the braided suture is considered not suitable for wound infection prevention because it can easily worsen the infection due to the attached bacteria between the suture tissues. Meanwhile, the braided suture is flexible and easier to tie, and the knot is difficult to break because of a large coefficient of friction. Studies that reviewed the types of suture showed the usefulness in infection prevention of the monofilament suture. A high-quality randomized controlled trial (RCT) comparing monofilament and braided sutures for occurrence of incisional hernias would be required in the future.31

Almost all laparotomy of hepatectomies were generally performed using combinations of vertical and horizontal incisions. Therefore, we separately investigated midline and transverse incisions in this study. The methods of incision were J-shaped, reversed L-shaped, reversed T-shaped, and Mercedes incisions. We excluded other incision methods.

Anatomically, the midline line incision was made through the stiff fascia called the linea alba (white line) in between the left and right rectus abdominis muscles. The linea alba is the part where the fascia of the rectus abdominis muscles are folded and united. Generally, when an incision is made on the linea alba, the rectus abdominis muscle is not incised.

In contrast, the left and right rectus abdominis fibers have a vertical orientation; thus, a horizontal incision always reaches the rectus abdominis muscle. In addition, the external oblique, internal oblique, and transverse abdominis muscles overlap on the lateral side of the rectus abdominis muscle. Horizontal incisions usually also extend to these muscles.

Therefore, in the closure of the midline incision, two layers, the linea alba and the skin, are closed; however, the horizontal incision would require a three-layer closure because of the need to close the anterior and posterior fascias of the rectus abdominis muscles. Similarly, the lateral side of the rectus abdominis, including the external oblique, internal oblique, and transverse abdominis muscles, also require separate closures of the anterior and posterior fascias.

In summary, the difference between a midline and a transverse incision is based on whether or not the muscle is incised and the number of layers of fascia to be sutured. Therefore, this difference explains the different risk factors for abdominal incisional hernia at different sites. We confirmed that a three-layer closure was performed for the horizontal incision and a two-layer closure was performed for the vertical incision in all institutes.

As a result, superficial and deep incisional SSIs, which indicate the occurrence of wound infection, were found to be risk factors for horizontal incisional hernias, whereas closure methods and suture types were not. Contrariwise, for the midline hernias, the closure method (interrupted suture) was identified as the main risk factor.

Regarding the impact of running and interrupted sutures on the occurrence of midline incisional hernias, some studies showed no difference, whereas others reported that running sutures were associated with better outcomes.4, 32-36 Diener et al14 stated that the incidence of abdominal incisional hernia was lower with running sutures than with interrupted sutures for midline wounds was used in 14 RCTs in their systematic review (odds ratio: 0.59; P < .001). For this reason, they reported that the running suture tended to evenly distribute the pressure on the whole wound, thus reducing the risk of amputation of the fascia by the suture.37, 38 In addition, a running suture requires fewer knots than the interrupted suture, thus reducing the incidence if SSI, since bacteria mainly attach to the knots. On the other hand, the interrupted suture was reportedly associated with better drainage of ascites from the gaps between the sutures; thus, the interrupted suture not only improves wound healing, but also reduces the accumulation of fluid and pus in the abdominal cavity.39 Whichever way, the problem-solving process has not been concluded, and an RCT (CONTINT Study) on the impact of interrupted and running sutures on midline incisions is ongoing.39

In this study we conducted separate investigations for midline and transverse incision sites. As the posterior and anterior parts of the fascia were separately closed in the transverse incision site, the suture type or method was not a risk factor, but rather wound infection. However, the closure method was a risk factor for midline incision sites. Certainly, nutrition and healing factors are generally important for abdominal incisional hernia prevention. Therefore, the closure of the midline incision might require a running suture, and preventive strategies for incisional SSI should be applied for transverse incisional sites, while maintaining preoperative nutrition and diabetes mellitus control.

Furthermore, 13 (21%) of the 62 patients with incisional hernia underwent surgical repair: open primary closure, open mesh repair, and laparoscopic mesh repair in three (23.1%), four (30.8%), and six (46.1%) patients, respectively.

his study had certain limitations. First, it had a retrospective design. Moreover, the diagnosis of abdominal incisional hernia was based on clinical symptoms, not on imaging evaluations such as computed tomography. Therefore, asymptomatic patients with abdominal incisional hernia might have been excluded from this study. Second, this study was a multicenter retrospective study; hence, perioperative management including enhanced recovery after surgery, nutritional support, and infection control were different at each institution. However, since all participating institutions were board-certified training institutions for expert surgeons of the Japanese Society of Hepato-Biliary-Pancreatic Surgery, the quality of surgical skills including suturing techniques during hepatectomy was guaranteed.

5 CONCLUSION

The risk factors for abdominal incisional hernia after open hepatectomy depend on the wound site. For transverse incisions, wound infection may primarily contribute to the development of abdominal incisional hernias. However, the suture method may be the most important factor in the development of midline abdominal incisional hernias. We recommend the implementation of systemic nutrition and blood glucose monitoring.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Shoji Momokawa from the Center for Clinical Research and Advanced Medicine, Shiga University of Medical Science Hospital, Shiga, Japan, for statistical advice.

DISCLOSURES

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest for this article.

Funding: No funding was received.

Author Contributions: HI, MK, and SK designed the study and analyzed patient data. HI, MT, FH, MU, TN, ST, TN, TN, MK, and SK collected data. HI and SK drafted the article. All authors have read and approved the final version of the article.

ETHICAL STATEMENT

The protocol for this multicenter research project was approved by a suitably constituted Ethics Committee of each institution, and it conforms to the provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki. Committee of principal institution Approval No. R2018-006. Informed consent was obtained from the patients and/or guardians.