Beef cattle farmers’ marketing preferences for selling local beef

Abstract

To meet the growing consumer demand for local foods, there has been increased interest by farmers to produce local foods. One facet of meeting this demand is how farmers may prefer to market their locally produced products. In this study, we examine beef cattle farmers’ marketing preferences for selling a Tennessee Certified Beef product. Data from a 2016 Tennessee beef cattle farmer survey (n = 428) was used to estimate a multinomial logit model of the probability of farmers preferring a particular marketing arrangement. The most commonly selected marketing arrangement was a farmer cooperatively owned processing facility (43%), followed by a beef marketing cooperative (39%), and private contracting of finished cattle to a third party for slaughter (18%). Factors influencing participation in the specific marketing arrangements included farmer and farm characteristics, risk preferences, and location.

1 INTRODUCTION

US consumers have become increasingly interested in consuming local foods. According to Packaged Foods (2015), local food sales in the United States grew from $5 billion in 2008 to $12 billion in 2014. While local food sales represent only about 2% of all retail food and beverage sales (Packaged Foods, 2015), consumer research has indicated this percentage is likely to increase. For example, research has found that consumers will pay more for local food products ranging from produce to beef (e.g., Carpio & Isengildina-Massa, 2009; Costanigro, McFadden, Kroll, & Nurse, 2011; Loureiro & Hine, 2002; Onozaka & Mcfadden, 2011; Gracia, Barreiro-Hurlé, & Galán, 2014; Dobbs et al., 2016; Merritt, DeLong, Griffith, & Jensen et al., 2018). In response to consumers’ increased preference for local foods, an increase in farmer sales of local foods has occurred. In the past decade, the number of farmers markets listed in the National Farmers Market Directory has nearly doubled in size reaching 8,687 farmers markets in 2017 (Agricultural Marketing Service, 2017). In 2015, US farmers produced and sold $8.7 billion of local food products (USDA Census of Agriculture, 2015). Of these local food sales, 35% were sold directly to consumers, 27% were sold to retailers and 39% were sold to other vendors of local foods (USDA Census of Agriculture, 2015). While research regarding consumer preferences for local foods is vast, little is known about farmers’ preferences regarding their preferred marketing methods for selling local foods. Therefore, we contribute to the literature on local foods by examining beef cattle farmers’ marketing preferences for selling local beef using a study of Tennessee producers.

As in many other states, the local foods movement in Tennessee has resulted in additional consumer demand for locally produced products. In 2015 in Tennessee, there were an estimated 4,148 farms that sold local foods resulting in $59 million in sales (USDA Census of Agriculture, 2015). With respect to beef, the research found that Tennessee beef consumers would pay a premium for a Tennessee produced beef product (Dobbs et al., 2016; Merritt et al., 2018). Merritt et al. (2018) found consumers would pay an average premium of $2.42/lb for Tennessee Certified Beef (TCB) steak and $1.15/lb for TCB ground beef. While there is consumer demand for a local Tennessee beef product, currently most Tennessee beef producers are classified as cow–calf operations and very few farms finish their cattle in the state.1 In fact, >90% of cattle originating in Tennessee are harvested out-of-state (USDA National Agricultural Statistical Service, 2017a, 2017b). While finishing cattle is not widely practiced within the state at this time, McLeod et al. (2018) still found substantial Tennessee farmer interest in finishing cattle and selling them through a TCB Program.

Given Tennessee cattle farmers’ interest in selling local beef, it is important to determine what marketing arrangement would be preferred by beef cattle farmers to sell their local beef. Furthermore, as previously stated, while there is well-documented research concerning consumer preferences for local foods (e.g., Carpio & Isengildina-Massa, 2009; Costanigro et al., 2011; Dobbs et al., 2016; Gracia et al., 2014; Loureiro & Hine, 2002; Merritt et al., 2018; Onozaka & Mcfadden, 2011), research is needed examining farmer preferences regarding their preferred marketing structure for selling local products. Therefore, the goal of this study is to examine Tennessee beef cattle farmer preferences for selling local beef through the following marketing arrangements: selling finished cattle by contract or broker to a third party for slaughter, farmer cooperatively owned processing facility, and a farmer marketing cooperative that markets beef to a third party. In particular, findings from this study can be of use to industry participants and policymakers because Tennessee currently has no beef marketing or processing cooperatives. In addition to determining Tennessee beef farmers’ preferred marketing structure for selling their beef, this study will also ascertain how farm characteristics, farmer demographics, and farmer attitudes influence farmers’ preferences to sell beef through each specific marketing arrangement. Finally, this study will also provide measures regarding the quantity of TCB that might be sold through the various marketing arrangements. Quantity information could be helpful in determining the feasibility of each type of marketing arrangement for selling TCB. Results of this study provide insight to policymakers who may be interested in designing an in-state branding program for beef and to researchers and policymakers interested in farmers’ preferences regarding preferred marketing structures for selling local foods.

2 PREVIOUS LITERATURE AND HYPOTHESIZED RESULTS

Previous studies have examined marketing alternatives for selling beef cattle (Gillespie, Basarir, & Schupp, 2004; Gillespie, Bu, Boucher, & Choi, 2006; Gillespie, Sitienei, Bhandari, & Scaglia, 2016) have examined factors influencing interest and membership in cooperatives (K. Jensen, English, Clark, & Menard, 2011; K. L. Jensen, Roberts, Bazen, Menard, & English, 2010; Kilmer, Lee, & Carley, 1994; Pace & Robinson, 2012; Puaha, 2003; Wachenheim, deHillerin, & Dumler, 2001). These studies found that interest and membership in cooperatives and preferences regarding marketing alternatives for selling beef cattle are influenced by farm characteristics, farmer demographics, and farmer attitudes. Similarly, we hypothesize farmers’ decision regarding how to sell their beef through a TCB Program will be influenced by farm characteristics, farmer demographics, and farmer attitudes.

2.1 Farm characteristics

Kilmer et al. (1994), K. L. Jensen et al. (2010), and Pace and Robinson (2012) found that larger farmers were less likely to be members of cooperatives. Meanwhile, Wachenheim et al. (2001), Puaha (2003), and K. Jensen et al. (2011) found that larger farms were more likely to belong to cooperatives. Gillespie et al. (2016) also found that larger farms were more likely to use multiple marketing channels. While previous research has found mixed results regarding how operation size is related to cooperative membership, we hypothesize larger farms with more animal units will be more likely to prefer to sell finished cattle to a third party for slaughter and be less likely to want to belong to a processing and marketing cooperative (Table 1). We hypothesize this because larger farms would be more able to put together a truckload of cattle to ship to a slaughter facility than smaller operations.

| Variable names | Description | Hypothesized sign for marketing arrangement 1, 2, 3 | Mean/% |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable | |||

| Preferred marketing arrangement | 1 = sell finished cattle by contract or broker to third party for slaughter | 18.5% | |

| 2 = farmer cooperatively owned processing facility | 43.0% | ||

| 3 = farmer marketing cooperative that markets beef to a third party | 38.6% | ||

| Independent variables | |||

| Farm characteristics | |||

| AnimalUnits | Animal Unitsa | +, −, − | 104.618 |

| East | 1 if located in East Tennessee, 0 otherwise | +, −, − | 31.1% |

| West | 1 if located in West Tennessee, 0 otherwise | +, −, − | 19.6% |

| Middle | 1 if located in Middle Tennessee, 0 otherwise (omitted category) | NA | 49.3% |

| FedInspect | 1 if located in county with or adjacent to a county with a federally inspected slaughter facility, 0 otherwise | +, −, + | 45.6% |

| FedInspect×Eastb | 1 if located in county with or adjacent to a county with a federally inspected slaughter facility and in East Tennessee, 0 otherwise | +, −, + | 14.0% |

| FedInspect×Westb | 1 if located in county with or adjacent to a county with a federally inspected slaughter facility and in West Tennessee, 0 otherwise | +, −, + | 11.9% |

| Farmer demographics | |||

| Age | Farmer age in years | +, −, − | 51.895 |

| College | 1 if college graduate, 0 otherwise | −, +, + | 57.9% |

| PrivTreaty/Packer | 1 if use private treaty for freezer beef or sell directly to packer, 0 otherwise | +, −, − | 8.4% |

| Sole | 1 if sole proprietor, 0 otherwise | −, +, + | 79.7% |

| HHInc | Household Income ($1,000) | −, +, + | 131.565 |

| FullTimeBeef | 1 if >50% of household income is from beef operations, 0 otherwise | −, +, + | 17.1% |

| FullTimeBeef×HHIncc | FullTimeBeef × HHInc interaction | −, +, + | 17.523 |

| Farmer attitudes | |||

| RiskNewMkt | Willingness to take risks finding new market outlets (1 = not at all, … 10 = very willing) | −, +, − | 7.794 |

| BarrierForwardCont | Potential barrier of using cash forward contracting (1 = not at all, … 5 = complete barrier-would not participate) | +, −, − | 2.098 |

| BarrierCoopPrice | Potential barrier of having to accept a price negotiated by a cooperative or marketing alliance (1 = not at all, … 5 = complete barrier-would not participate) | +, −, − | 2.044 |

| PremiumTCB | Agreement that consumers would pay a premium for TCB (1 = strongly disagree, … 5 = strongly agree) | −, −, + | 3.521 |

- Note. n = 428.

- TCB: Tennessee Certified Beef.

- a Animal units are calculated as 0.92 × cows + 0.08 × calves + 1.35 × bulls + 0.6 × backgrounder calves + 0.6 × stocker calves + 0.92 × dairy cows + 0.8 × replacement heifers + 0.8 × miscellaneous cattle (Source: Pratt & Rasmussen, 2001).

- b 60.7%, 39.8%, and 45.1% of the cattle farmers are located in counties in close proximity to a federally inspected facility in West, Middle, and East Tennessee, respectively.

- c The average household income among full-time beef farmers is $112,007 (n = 152), while the average household income among those not full time is $142,337 (n = 276).

Tennessee is divided into three grand divisions: East, Middle, and West. The West is characterized by row cropping and larger farming operations. The Middle, where the majority of cow–calf and backgrounding operations are located, is characterized by low rolling hills and more moderately sized farming operations. The East is a more mountainous region with smaller farmland parcels. Middle Tennessee has the largest number of beef cattle operations and the largest share of beef cow inventory (58.7%), with the East having the second largest share (30.5%) and the West the smallest share (10.8%; USDA National Agricultural Statistical Service, 2018).2 Since Middle Tennessee has the most beef cattle, they also likely have the most beef cattle farmers and most potential for forming cooperatives compared to the other regions. Therefore, we hypothesize farmers in East and West Tennessee, compared to Middle Tennessee, will be more likely to prefer to sell finished cattle to a third party while farmers in Middle Tennessee will be more likely to prefer to belong to a processing or beef marketing cooperative (Table 1). West, Middle, and East Tennessee were also included in the regression to control for unobserved heterogeneity associated with these regions.

At the time of this study, there were 13 federally inspected livestock slaughter facilities in Tennessee where producers could have their cattle processed and then sell their beef at a retail level to restaurants or directly to consumers (Pepper, Leffew, and Holland,2016). Of these processing facilities, five were located in West Tennessee, four in Middle Tennessee and four in East Tennessee. It is hypothesized that farmers who are located near a federally inspected slaughter facility will be more likely to prefer selling finished cattle to third parties for slaughter or joining a marketing cooperative that markets beef to a third party since they already have access to a processing facility. Meanwhile, we predict farmers who are not located near a federally inspected slaughter facility will be more likely to prefer a cooperatively owned processing facility (Table 1).

The interaction of location and proximity to a federally inspected processing facility is also hypothesized to impact farmers’ preferences for marketing arrangement. In West, Middle, and East Tennessee, 61%, 40%, and 45%, respectively of cattle farmers are located in counties in close proximity to a federally inspected slaughter facility. We hypothesize the farmers located by a federally inspected slaughter facility in East and West Tennessee will be more likely to prefer to sell finished cattle to a third party for slaughter or belong to a beef marketing cooperative since they already have the most access to a processing facility (Table 1).

2.2 Farmer demographics

Studies have found that younger hog farmers (Wachenheim et al., 2001) and wheat farmers (Puaha, 2003) were more likely to belong to a cooperative. Also, Gillespie et al. (2004) found that younger producers were more likely to use private treaties and retained ownership for marketing their cattle than their older counterparts. Therefore, we hypothesize that the older producers are, the less likely they would join the cooperatively owned processing facility and the marketing cooperative, and the more likely they would prefer to market their cattle to a third party (Table 1).

Previous research found that more educated producers were more likely to be cooperative members (K. L. Jensen et al., 2010; Puaha, 2003; Wachenheim et al., 2001). Thus, it is hypothesized that producers with more education will prefer the marketing and processing cooperative compared to selling finished cattle to a third party for slaughter (Table 1). If cattle farmers already sell freezer beef and cattle directly to a packer, it is hypothesized they will prefer to sell finished cattle to a third party for slaughter since they already have a system in place for slaughtering their cattle and selling beef. Thus, the need to belong to a processing or marketing cooperative does not exist (Table 1). No previous research was identified that examined how farm structure impacted cooperative participation. We hypothesize sole proprietor farming operations will be more likely to prefer the processing or marketing cooperative since a sole proprietor may be a smaller operation size than other entity types (e.g., corporation) and prefer to join a cooperative (Table 1).

Puaha (2003) found that wheat cooperative members had a higher share of their income from wheat farming than nonmembers. K. L. Jensen et al. (2010) found that farmers with moderate farm income and high debt were less likely to have an interest in a poultry litter cooperative. K. Jensen et al. (2011) found that farmers with higher off-farm income and moderate debt were more likely to have an interest in a switchgrass cooperative. Given the results indicate that higher incomes are associated with cooperative membership, we hypothesize that farmers with greater income will prefer the marketing or processing cooperative while farmers with lower incomes will prefer to sell their beef to a third party for slaughter. Gillespie et al. (2006) found that producers who farm as a hobby might not want to participate in a beef strategic alliance because they do not wish to devote the time and effort to change management practices. Kilmer et al. (1994) found that as the percent of income from the dairy increases, the more likely the dairy farmer will be a cooperative member. Therefore, we predict that farmers who have over half of their income from beef operations will be more likely to prefer marketing and processing cooperatives while farmers who derive less than half of their incomes from the beef will prefer selling their finished cattle to a third party for slaughter (Table 1). Similarly, we hypothesize that full-time beef producers with higher household incomes will be more likely to prefer marketing and processing cooperatives (Table 1).

2.3 Farmer attitudes

K. Jensen et al. (2011) found that producers who were willing to take more risks had increased preferences for a switchgrass cooperative. Additionally, of the three marketing alternatives, we presented to participants, cooperatively owning a processing facility is the most capital intensive and, thus, riskiest. Therefore, it is hypothesized that farmers who are more willing to take risks will also have increased preferences for the processing cooperatives compared to the other marketing structures (Table 1). As farmers consider using cash forward contracting as an increased barrier, it is hypothesized that farmers will prefer to sell cattle to a third party for slaughter instead of joining a processing or marketing cooperative (Table 1) which is largely due to beef cattle farmers’ desire for marketing flexibility and independent nature. As farmers consider having to accept a price negotiated by a cooperative or marketing alliance as more of a barrier, we predict farmers will prefer not to join the marketing or processing cooperative (Table 1). Finally, as farmers are more likely to agree that consumers would pay a premium for TCB, we hypothesize that they will most likely prefer a marketing cooperative to sell their beef (Table 1).

3 DATA

3.1 Data collection and survey

Beef cattle producers who participated in the Tennessee Agricultural Enhancement Program (TAEP) were surveyed to collect the data used in this study. There were 5,500 beef cattle producers participating in this program spread across the state in 2016. The survey was pretested through email of 275 producers in June and July 2017 and those included in the pretest were not invited to participate in the full survey. The full survey, which included revisions from the pretests, was emailed to 4,661 producers participating in TAEP who had usable email addresses in August 2016. The email contained a link to a Qualtrics survey that producers then completed. A follow-up reminder email was sent a week after the initial email and a second reminder email was sent 2–3 weeks after that. To complete the survey, producers had to raise cattle in 2015 and be the primary decision maker. A total of 864 surveys were collected by mid-September, at which time the survey closed, resulting in a survey response rate of 18.5%.

- a)

Animal identification and recordkeeping

- b)

Final or processed products only include beef from Tennessee farms (calves to finished animal must be raised in Tennessee)

- c)

Slaughter occurs at a Federally Inspected facility in Tennessee

- d)

Beef grades Choice or Prime.”

Next, if the farmer was interested in the TCB Program, they were asked how they would prefer to sell their animals in the program with the options for selling being: (a) sell finished cattle by contract or broker to the third party for slaughter, (b) farmer cooperatively owned processing facility, or (c) farmer marketing cooperative that markets beef to a third party. The exact form of this survey question is available in the Appendix. The final section of the survey asked about farm characteristics, farmer demographics, and farmer attitudes. A copy of the survey is available from the authors upon request.

3.2 Economic model

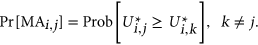

) exceeds the utility of choosing a different type of marketing arrangement for the branded beef

) exceeds the utility of choosing a different type of marketing arrangement for the branded beef  ), where J = 1, 2, 3 (1 = sell finished cattle to a third party for slaughter, 2 = farmer cooperatively owned processing facility, 3 = farmer marketing cooperative that markets beef to a third party) and j ≠ k. Hence, farmer i will choose alternative j if:

), where J = 1, 2, 3 (1 = sell finished cattle to a third party for slaughter, 2 = farmer cooperatively owned processing facility, 3 = farmer marketing cooperative that markets beef to a third party) and j ≠ k. Hence, farmer i will choose alternative j if:

(1)

(1) (3)

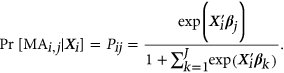

(3)The vector of explanatory variables for individual i ( ) is hypothesized to influence the preferred marketing arrangement for branded beef and includes farmer demographics, farm characteristics, and farmer attitudes (Table 1).

) is hypothesized to influence the preferred marketing arrangement for branded beef and includes farmer demographics, farm characteristics, and farmer attitudes (Table 1).  is the vector of estimated coefficients associated with the explanatory variables.

is the vector of estimated coefficients associated with the explanatory variables.

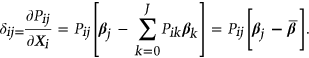

(4)

(4)The standard errors around the marginal effects were calculated using the Delta method (Greene, 2012). The marginal effects are estimated by taking the average marginal effect over the estimation sample.

4 RESULTS

4.1 Preferred marketing arrangements and farm demographics

While a total of 555 beef cattle farmers were interested in participating in the TCB Program, a total of 428 farmers responded to all of the questions needed for the analysis of farmers’ preferred marketing arrangement for selling a branded beef product. Among the marketing arrangements (Preferred Marketing Arrangement), 43.0% would prefer to market TCB through a farmer cooperatively owned processing facility, 38.6% prefer a farmer marketing cooperative that markets beef to a third party, and 18.5% prefer to sell finished cattle by contract or broker to a third party for slaughter (Table 1).

On average, the number of beef cattle animal units managed and marketed (AnimalUnits) was 104.62.4 The Tennessee average herd size is 26 head of cattle; however, this number does not include stocker operations which tend to be much larger than cow–calf operations (USDA Census of Agriculture, 2012). This discrepancy on average herd size may also exist since only cattle producers who had participated in TAEP were surveyed and they may be larger producers than average. About 31.1% of the respondents were located in East Tennessee, while 19.6% were located in West Tennessee, and 49.3% were located in Middle Tennessee. This is consistent with where beef cattle are located in the state since 35%, 11%, and 54% of the cattle and calves in the state are located in East, West, and Middle Tennessee, respectively (USDA National Agricultural Statistical Service, 2018). Just under 46% of producers were located in counties having or bordering a county with a federally inspected slaughter facility (FedInspect). About 14% were in a county in East Tennessee with proximity to a federally inspected slaughter facility (FederalInspect × East), while about 11.9% were located in West Tennessee counties with proximity to a federally inspected slaughter facility (FedInspect × West).

The average age of the responding farmers was nearly 52 years which is consistent with the average age of a US farmer being 58 (USDA Census of Agriculture, 2012). Nearly 58% of the sample were college graduates and the average household income (including farm and nonfarm income) was $131,565. About 8.4% of producers already sold freezer beef through private treaty or sold cattle directly to a packer. Nearly 80% of the respondents were sole proprietors and 17.1% derived at least half of their household income from their beef cattle enterprises (FullTimeBeef).

Producers considered themselves fairly risky when finding new market outlets for beef (RiskNewMkt) with an average score of nearly 8 out of 10. Both potential barriers of having to use cash forward contracting (BarrierForwardCont) or having to accept a price negotiated by a cooperative or marketing alliance (BarrierCoopPrice) were considered moderate barriers with values of just over 2 out of 5. The farmers were in agreement with the statement that consumers would pay a premium for TCB (PremiumTCB).

4.2 Multinomial logit model results

To estimate a multinomial logit model, one of the preferred marketing structure options had to be treated as the omitted category of the dependent variable for the analysis. Thus, private contracting was the marketing structure that was omitted from analysis and selected as the base outcome. However, when presenting marginal effects, this marketing option is recovered from analysis and discussed. The estimated multinomial logit model is shown in Table 2. The log likelihood ratio test shows that the model is significant overall. The model correctly predicts just over 53% of the observations. The mean variance inflation factor (VIF) was 1.81 and the max VIF was 3.53; thus, multicollinearity was not a concern with the model.

| Processing cooperative | Marketing cooperative | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | Standard error | Coefficient | Standard error | |

| Farm characteristics | ||||

| AnimalUnits | −0.001 | 0.001 | −0.002** | 0.001 |

| East | 0.303 | 0.459 | 0.476 | 0.464 |

| West | −0.887 | 0.557 | −0.270 | 0.522 |

| FedInspect | 0.268 | 0.430 | 0.309 | 0.435 |

| FedInspect×East | −1.315** | 0.672 | −1.403** | 0.677 |

| FedInspect×West | 1.219 | 0.807 | 0.434 | 0.790 |

| Farmer demographics | ||||

| Age | 0.028** | 0.012 | 0.036*** | 0.012 |

| College | −0.387 | 0.304 | 0.094 | 0.307 |

| PrivTreaty/Packer | −0.904* | 0.464 | −0.879* | 0.468 |

| Sole | 0.370 | 0.360 | −0.083 | 0.349 |

| HHInc | −0.001 | 0.002 | −0.003** | 0.002 |

| FullTimeBeef | −1.958** | 0.874 | −1.155 | 0.849 |

| FullTimeBeef×HHInc | 0.017* | 0.009 | 0.010 | 0.009 |

| Farmer attitudes | ||||

| RiskNewMkt | 0.212*** | 0.081 | 0.011 | 0.079 |

| BarrierForwardCont | 0.070 | 0.146 | −0.014 | 0.148 |

| BarrierCoopPrice | −0.187 | 0.161 | −0.093 | 0.162 |

| PremiumTCB | 0.357*** | 0.177 | 0.262 | 0.178 |

| Constant | −3.115** | 1.336 | −2.088 | 1.339 |

- Note: n = 428. Log likelihood = −411.388, log likelihood ratio test (34 df) = 69.38***. Percent correctly classified = 53.74. Mean variance inflation factor (VIF) = 1.81 and the maximum VIF = 3.5.

- *,**,***Statistical significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels, respectively.

In terms of farm characteristics, only the interaction variable FedInspect×East was significant in influencing producers’ preference to join a processing cooperative to market their TCB compared to selling finished cattle to a third party for slaughter. Meanwhile, AnimalUnits and FederalInspect×East were both found to influence a producers’ preference to sell TCB through a cooperative that markets beef to a third party compared to selling finished cattle to a third party for slaughter.

With regard to farmer demographics, Age, PrivTreaty/Packer, FullTimeBeef, and FullTimeBeef×HHInc were all found to influence producers’ preferences to join a processing cooperative to market their beef compared to selling finished cattle to a third party for slaughter. Age and PrivTreaty/Packer also impacted producers’ preferences to join a marketing cooperative to sell their TCB beef. Additionally, HHInc also had an impact on producers’ desire to market their beef through a marketing cooperative as opposed to selling finished cattle to a third party for slaughter.

Farmer attitudes only had an impact on farmers’ preference to join a processing cooperative compared to private contracting finished cattle to a third party for slaughter. If farmers had increased risk preferences (RiskNewMkt) and thought consumers would pay a premium for TCB (PremiumTCB) they were more likely to join a processing cooperative compared to private contracting finished cattle to a third party for slaughter.

4.3 Multinomial logit marginal effects

The estimated marginal effects for the multinomial logit model, which were calculated following Equation (4), are shown in Table 3.

| Private contract | Processing cooperative | Marketing cooperative | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marginal effect | Standard error | Marginal effect | Standard error | Marginal effect | Standard error | |

| Farm characteristics | ||||||

| AnimalUnits | 0.0002** | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.0002 | −0.0003 | 0.0002 |

| East | −0.052 | 0.058 | −0.007 | 0.070 | 0.059 | 0.070 |

| West | 0.078 | 0.065 | −0.157 | 0.098 | 0.079 | 0.093 |

| FedInspect | −0.039 | 0.054 | 0.012 | 0.067 | 0.027 | 0.067 |

| FedInspect×East | 0.183** | 0.083 | −0.075 | 0.108 | −0.108 | 0.108 |

| FedInspect×West | −0.112 | 0.098 | 0.206 | 0.129 | −0.094 | 0.126 |

| Farmer demographics | ||||||

| Age | −0.004*** | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.004** | 0.002 |

| College | 0.020 | 0.038 | −0.102** | 0.047 | 0.082* | 0.048 |

| PrivTreaty/Packer | 0.120** | 0.054 | −0.065 | 0.089 | −0.055 | 0.089 |

| Sole | −0.019 | 0.043 | 0.096 | 0.061 | −0.077 | 0.059 |

| HHInc | 0.0003 | 0.0002 | 0.0002 | 0.0003 | −0.0005* | 0.0003 |

| FullTimeBeef | 0.210** | 0.106 | −0.259* | 0.137 | 0.049 | 0.133 |

| FullTimeBeef ×HHInc | −0.002 | 0.001 | 0.002* | 0.001 | −0.001 | 0.001 |

| Farmer attitudes | ||||||

| RiskNewMkt | −0.015 | 0.010 | 0.046** | 0.013 | −0.031** | 0.013 |

| BarrierForwardCont | −0.004 | 0.018 | 0.018 | 0.024 | −0.014 | 0.024 |

| BarrierCoopPrice | 0.019 | 0.020 | −0.027 | 0.027 | 0.008 | 0.027 |

| PremiumTCB | −0.042* | 0.022 | 0.039 | 0.029 | 0.003 | 0.029 |

- Notes: n = 428.

- TCB: Tennessee Certified Beef.

- *,**,***Statistical significance at the 10%, 5% and 1% levels, respectively.

4.3.1 Farm characteristics

In terms of farm characteristics, only AnimalUnits and FedInspect×East were significant in determining farmers’ preferences to sell finished cattle to a third party for slaughter (Private Contract). No farm characteristics were significant in explaining farmers’ preferences for either the processing cooperative or the marketing cooperative. For each additional 100 animal units (AnimalUnits) on a farm, the probability of a farmer selecting to sell finished cattle to a third party for slaughter increased by 2%. This finding is consistent with our hypothesis that as the number of animal units increased, we predicted producers would be more likely to sell finished cattle to a third party for slaughter than prefer to join a marketing or processing cooperative. A possible explanation for this is that as producers are larger, they have an easier time putting together a truckload of cattle to send to slaughter and would not need the help of a processing or marketing cooperative to market their TCB.

To interpret the significant marginal effect (ME) of FedInspect×East, the marginal effects for East, FedInspect, and FedInspect×East were added together to calculate an overall effect equal to 9.2% (MEEast+MEFedInspect + ME FedInspect×East = − 0.052 − 0.039 + 0.183 = 0.092). Thus, if farmers were located in East Tennessee in a county or adjacent to a county with a federally inspected slaughter facility, they were 9.2% more likely to prefer to sell finished cattle to a third party for slaughter, which is consistent with our hypothesis.

4.3.2 Farmer demographics

In terms of farmer demographics, several variables were significant in explaining farmers’ preferences for different marketing methods of TCB. Age was significant in explaining producers’ preferences for private contracting and marketing cooperative. For private contracting, the marginal effect on farmer age (AGE) was negative. As a farmer was an additional year older, the probability of the farmer selecting a private contract decreased by 0.4%. Meanwhile, if a farmer was an additional year older, they were 0.4% more likely to choose a marketing cooperative. This is opposite from our hypothesis that as farmers were younger they would be more likely to join a cooperative compared to private contracting.

Being college educated had an impact on producers’ selection of processing and marketing cooperatives. If a farmer was a college graduate (College) they were 10.2% less likely to choose a processing cooperative and 8.2% more likely to choose a marketing cooperative. We hypothesized that college graduates would be more likely to choose a cooperative to sell their TCB than through private contracting. If producers already sold freezer beef or sold cattle directly to a packer, they were 12% more likely to use private contracting to sell finished cattle for slaughter, a finding that is consistent with our hypothesized results. Every thousand dollars of income decreased a farmers’ probability of choosing a marketing cooperative by 0.05%. We hypothesized that farmers with higher incomes would be more likely to choose a cooperative to market their TCB.

If farmers received over half of their income from their beef operations (FullTimeBeef), they were 21% more likely to prefer to sell their cattle through a private contract and were nearly 26% less likely to choose a processing cooperative as their marketing structure. We hypothesized that full-time farmers would be less likely to prefer their cattle be sold through a private contract. However, this result could be related to the result we found for animal units: as a farmer is larger, perhaps the farmer is also a full-time beef producer and does not need the help of a cooperative to sell his or her beef. However, the interaction of FullTimeBeef×HHInc had a significant and positive marginal effect when evaluating household income at the sample mean. If the overall effect from household income and deriving at least half of household income from beef enterprises (HHInc, FullTimeBeef, and FullTimeBeef×HHInc) is calculated at the mean of household income, the overall effect is MEFullTimeBeef + MEFullTimeBeef×HHInc ×  + MEHHInc ×

+ MEHHInc ×  = -0.259 + 0.002*131.565 + 0.0002*131.565 = 0.0304 or an increase of 3.04%. Thus, assuming a full-time farmer had the sample average household income, they were 3.04% more likely to prefer a processing cooperative to market their beef cattle. It can be noted that the effects of greater household income and being full-time beef farmers are negative up to $117,727 (calculated as MEFullTimeBeef/[MEFullTimeBeef×HHInc+ MEFullTimeBeef×HHInc] = −0.259/[0.002 + 0.0002]). Thus, farmers who derive half of their household income from beef and have income >$117,727 are more likely to choose the processing cooperative to market their cattle, which is consistent with our hypothesized results.

= -0.259 + 0.002*131.565 + 0.0002*131.565 = 0.0304 or an increase of 3.04%. Thus, assuming a full-time farmer had the sample average household income, they were 3.04% more likely to prefer a processing cooperative to market their beef cattle. It can be noted that the effects of greater household income and being full-time beef farmers are negative up to $117,727 (calculated as MEFullTimeBeef/[MEFullTimeBeef×HHInc+ MEFullTimeBeef×HHInc] = −0.259/[0.002 + 0.0002]). Thus, farmers who derive half of their household income from beef and have income >$117,727 are more likely to choose the processing cooperative to market their cattle, which is consistent with our hypothesized results.

4.3.3 Farmer attitudes

With respect to farmer attitudes, only risk attitudes (RiskNewMkt) and producers’ agreement that they would receive a premium for TCB (PremiumTCB) impacted preferred marketing structure. As farmers were more likely to believe consumers would pay a premium for TCB, they were 4.2% less likely to prefer to sell their beef through a private contract. This is somewhat consistent with our hypothesis that farmers would be more likely to prefer a marketing cooperative to market their TCB as they more strongly agreed that TCB would garner a premium. Being willing to take on risks to find new markets (RiskNewMkt) had a significant and positive marginal effect on a farmers’ probability of choosing a processing and marketing cooperative. If a farmer was very willing to take on such risks (a value of 10), this increased their probability of choosing a processing cooperative as their preferred marketing method by 46% and decreased their likelihood of choosing a marketing cooperative by 31%. This is consistent with the hypothesis that a processing cooperative may be viewed as the riskiest marketing structure option by the producers.

4.4 Quantity of TCB farmers would supply across market arrangements

In addition to asking farmers about their preferred marketing structures for selling local beef, farmers were also asked how much beef they would supply through each marketing channel. Farmers selecting to sell finished cattle to a third party for slaughter would supply, on average, 94,887 pounds of beef per farm. Meanwhile, farms with a preferred marketing structure of processing cooperative were willing to supply, on average, 50,109 pounds of beef, and those choosing a marketing cooperative were willing to supply 52,677 pounds of local beef. This is consistent with our model results that larger farms were more likely to prefer to sell finished cattle to a third party for slaughter (Table 3). Hence, although the majority of farmers would prefer to sell their local beef through cooperatives (Table 1), the quantity of beef per farm they would sell is smaller than for those preferring private contracts.5 When the total quantities of beef were calculated for each type of marketing arrangement across all farms, about 37.14% of the total pounds were estimated to originate from those preferring processing cooperatives, 33.82% from those preferring marketing contracts, and 29.03% from those preferring private contracting.

Dalton, Holland, and Hubbs (2007) surveyed federally inspected facilities that can accept cattle for immediate slaughter in Tennessee and found that respondents slaughtered, on average, 886 head per facility and 7,976 head cumulatively across all facilities. Capacity, however, averaged 3,121 head per plant. Pepper et al. (2016) updated the Dalton et al. (2007) survey and found that for all 13 Tennessee federally inspected facilities cited as accepting cattle for immediate slaughter (including respondents and nonrespondents), this would be around 40,573 head capacity across all facilities and about 11,518 head slaughtered per year. The number of pounds that farmers preferring private contracts would supply was 94,877 pounds per farm annually, with 71 farms choosing this alternative or 6,736,977 pounds across the 71 farms. Assuming 1,300 pounds liveweight per animal, this is about 5,182 head supplied through private contracts. Using the same calculation for marketing cooperatives this results in 6,630 head, and 6,037 head for processing cooperatives, respectively. Hence if the total capacity across the 13 facilities is 40,473 head, with 11,518 head slaughtered per year, it appears that there is likely sufficient existing slaughter capacity in Tennessee to accommodate groups of farmers selling via these marketing arrangements. In particular, selling through private contracts and selling through marketing cooperatives could potentially be accommodated through existing facilities.

5 CONCLUSIONS

In accordance with increased consumer demand for local foods, there has been an increase in the sale of local foods (Packaged Foods, 2015). While previous literature has examined consumer preferences for local foods (e.g., Carpio & Isengildina-Massa, 2009; Costanigro et al., 2011; Dobbs, et al., 2016; Gracia et al., 2014; Loureiro & Hine, 2002; Merritt et al., 2018; Onozaka & Mcfadden, 2011), research is needed that examines farmers’ preferences for marketing local foods. Therefore, Tennessee cattle farmers’ preferences for marketing a local beef product was examined. While no state branding program is currently available in Tennessee, research has found that there is an interest from consumers to purchase TCB (Dobbs, et al., 2016; Merritt et al., 2018) and an interest by producers to sell TCB (McLeod et al., 2018). Furthermore, Tennessee currently has no beef marketing or processing cooperatives. Therefore, it is important to determine what type of marketing arrangement cattle farmers might prefer, what influences these preferences, and the quantity of TCB that might be supplied through these marketing arrangements.

It was discovered that farmers were most interested in marketing branded beef through a cooperative rather than through private contracts. This is a fascinating result considering no beef marketing cooperatives currently exist in Tennessee. Furthermore, Tennessee currently only had two agricultural marketing cooperatives as of 2016 (USDA Rural Development, 2016)6 However, it should be noted that participants were not given information about the upfront investment costs of a processing cooperative before the survey. This is a limitation of the study and future research should state marketing arrangement investment costs before having producers select their preferred marketing arrangement.

It was found that private contracts tended to be preferred by farmers with larger herd sizes, farms located in East Tennessee near a federally inspected slaughter facility, younger farmers, farmers whose primary income originated from beef enterprises, and farmers who were already selling freezer beef or beef directly to slaughter facilities through private contracts. This suggests that these farmers may have larger operations and in some cases may already be selling into retail or slaughter markets directly. As farmers were more likely to consider TCB a product that would garner a premium, they were less likely to prefer to private contract their fed cattle to a slaughter facility.

As farmers had more education and were a full-time beef producer, they were less likely to prefer to join a processing cooperative. However, farmers who were full-time beef producers who had household income greater than $117,727 were more likely to prefer the processing cooperative to market their cattle. As farmers were more willing to take on risks to find new marketing outlets, they were also more likely to prefer to join a processing cooperative. Finally, farmers who were older, more educated, and had lower household incomes were more likely to prefer to join a marketing cooperative. As farmers were riskier in finding new marketing outlets, they were less likely to prefer to join a marketing cooperative.

While this study provides insights into the types of marketing arrangements that farmers might prefer to sell TCB, many questions remain. For example, a processing cooperative would require significant upfront investment. Additional research could examine the terms and specifications of contracts and influences on amounts farmers might be willing to invest in a processing cooperative. Furthermore, the use of a self-reported survey, as in this study, is a limitation considering farmers may state they are willing to join a certain marketing structure, but their actions may differ from what they self-report. Future research should also examine farmers’ preferences for marketing products other than beef and how these marketing preferences vary by commodity and location.

APPENDIX A

The survey question participants were asked for the dependent variable is below. The first two responses were combined to form the “sell finished cattle by contract or broker to third party for slaughter” option. The third response was the “farmer cooperatively owned processing facility” option and the fourth response was the “farmer marketing cooperative that markets beef to a third party” option. The “other” option responses were omitted from analysis and accounted for less than four percent of observations.

- 1.

A third party (for example through a Private Party or Corporation) and I would sell my finished cattle by contract to that third party directly for slaughter

- 2.

A third party (for example through a Private Party or Corporation), and I would sell my finished cattle through a broker to that third party for slaughter

- 3.

A farmer cooperatively owned processing facility of which I would be a member or investor

- 4.

A farmer marketing cooperative of which I would be a member that markets our beef to the third party

- 5.

Other, please describe:_____________________________________

Biographies

Karen L. DeLong is an Assistant Professor of Agricultural and Resource Economics at the University of Tennessee, [email protected], 302 Morgan Hall, 2621 Morgan Circle, Knoxville, TN 37996. She earned her PhD in Business Administration (Agribusiness) from the W. P. Carey School of Business at Arizona State University, her MS in Agricultural, Food and Resource Economics at the Michigan State University, and a BS in Math and Economics at the Western Michigan University. Her current research interests include agricultural and food policy, international trade, livestock economics, and experimental economics.

Kimberly L. Jensen is a Professor at the Department of Agricultural and Resource Economics, The University of Tennessee, [email protected], 302 Morgan Hall, 2621 Morgan Circle, Knoxville, TN 37996. Dr Jensen holds a PhD in Agricultural Economics from the Oklahoma State University (1986), an MS in Agribusiness from the Arizona State University (1983), and a BS in Bio-Agricultural Sciences from the Arizona State University (1981). Her research interests include consumer preferences and willingness to pay for food and fiber products, farmer willingness to adopt new products and practices, agribusiness development, and bioenergy markets analysis.

Andrew P. Griffith is an Associate Professor at the Department of Agricultural and Resource Economics, The University of Tennessee, [email protected], 314 Morgan Hall, 2621 Morgan Circle, Knoxville, TN 37996. Dr Griffith holds a PhD in Agricultural Economics from the Oklahoma State University (2012), an MS in Agricultural Economics from the University of Tennessee (2009), and a BS in Agriculture from the Tennessee Tech University (2007). His research interests include livestock marketing, price risk management, production economics, farmer willingness to adopt new production and marketing strategies, and consumer and retail willingness to pay.

Elizabeth McLeod holds an MS in Agricultural Economics from the University of Tennessee (2017) and a BS in Applied Economics and Statistics from the Clemson University (2015). She is currently working for the USDA as an Agricultural Economist in the Risk Management Agency in Kansas City.

is (Greene,

is (Greene,