How to accomplish mission-driven work for emergency medicine educators

Supervising Editor: Wendy C. Coates

INTRODUCTION

Emergency medicine (EM) educators have increased academic and clinical demands in addition to personal obligations.1 In the academic world, there is always another committee to be on and meeting to attend. Given the endless possibility of tasks to partake in, emergency physicians are often left with trying to navigate which opportunities to pursue that will lead them to the optimal career path while avoiding feeling overwhelmed. In this paper, we will explore practical strategies to stop doing everything, realize your mission as an EM educator, and put in place a plan to execute it.

KNOW YOUR MISSION

Goal getting

There is a strong connection between goal setting and success.2 Academia often discusses the benefits of setting goals, but often putting them into practice proves difficult. We are often told to set S.M.A.R.T. goals, making sure the goals are specific, measurable, achievable, realistic, and timely.3, 4 One strategy to make this more manageable is to consider dividing long-term goals into multiple shorter term goals5 and then devise a plan for sequential completion of the smaller goals and track the incremental progress (Figure 1).6

Begin by thinking about your individual values and priorities.7 A list of what is personally important is critical for setting accurate goals. Most emergency departments have mission statements; follow their lead and write your own mission statement. You should include not only your values and vision for your career but also those for your personal life. It may be necessary to consider external factors, such as requirements for promotion in your department. This will help guide your career goals to align with your institutional goals to ensure promotion. Only by knowing your values and mission can you “goal get,” actually obtain your goals, and not just “goal set.”

Prioritize

The mere urgency effect is when people choose to perform urgent tasks with short completion windows instead of important long-term tasks with larger rewards.8 That explains why when we sit down to write that scholarly paper, we are instead replying to emails and phone notifications. The literature is clear that prioritizing effectively is key to doing mission-driven work.4, 7, 9

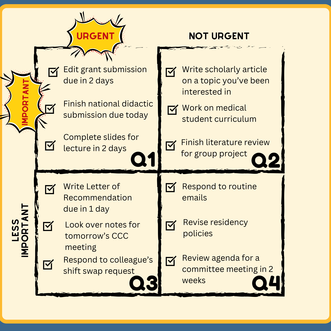

Prioritization requires thought and attention, processes that are some of the brain's most energy-hungry activities.10 The key to being productive is to intentionally devote time to important but less urgent tasks.5 These are the grant submissions due in 3–6 months or the lectures that got accepted at upcoming conferences months away. Prioritize based on importance, not just urgency. The Covey Time Management Matrix (Table 1) is a helpful way to organize tasks into quadrants based on importance and urgency.11, 12 Common examples for the EM educator have been included. Successful time management has been shown to enhance not only job performance but also well-being;13 emphasizing adapting the Covey Time Management Matrix can ultimate lead to greater fulfillment in mission-driven work.

|

Often people focus on Quadrant 1 (urgent and important) and Quadrant 3 (urgent and not important) tasks. However, it is important to set time aside for the quadrant two tasks, those that are not urgent but important, as they can provide balance and focus toward your mission as an EM educator.14 This is especially important to emergency physicians with variable schedules, where it is essential to plan ahead and prioritize. With a string of shifts coming up, it may be sensible to choose to work on a manuscript with an upcoming deadline instead of attending an optional meeting.

Consider spending 30 min a day on any Quadrant 2 tasks that are more than 30 days away. This will allow continued focus on important and not urgent tasks, while not being extremely burdensome on time.

EXECUTE YOUR MISSION

Learn where your time is going

Humans are poor at estimating how long it will take to complete a task, even if we have completed the task in the past.15 Often when sitting down to do nonclinical work, it can be easy to get distracted and focus can drift from the task at hand even without being aware of it. By doing a time audit, it is possible to make changes and prevent time-wasting activities.

There are several different ways to accomplish a time audit. One way is the traditional pen and paper (or notes on your computer) method. Keep an hourly time log of activities over 1 week.12 Alternatively, you can automate this with applications like RescueTime that run in the background on your devices and can do the time audit for you.14 A low-fidelity option is utilizing your iPhone's log of where your time is spent, which can be found in settings, under “screen time.” Many Android devices have similar features.

The most important step of this process is to self-reflect and analyze how your hours were spent.12, 16 When reviewing your logged hours, note when and for how long you were most productive as well as tasks that took longer than you expected.17 For EM educators, it is especially important to analyze how much time you spent on low-return work, work that is a support task and not goal-getting (e.g., email, unnecessary meetings). Consider how you can cut the time spent on these (e.g., outsourcing meeting scheduling or email replies to an administrator). By tracking your time, you can discover when you are the most productive, minimize low-return tasks, and optimize your schedule.18

Start your day with the most important task to accomplish

Willpower and decision making are limited resources.19 A single act of self-control impairs subsequent attempts at self-control given that willpower is finite. Therefore, prioritize the most difficult, urgent, and important work during the most alert and productive times.9 The willpower to work on a paper or grant is likely to be much higher early in the day than after lunch. Most people are at their highest cognitive capacity in the mornings.5 Use the mornings, or the time identified as your most productive based on your time audit, to schedule difficult tasks given the likely higher willpower reserve to accomplish them.17

Calendar your day, week, and month

Nir Eyal, the author of Indistractable, wrote “You can't call something a distraction unless you know what it's distracting you from.”20 Calendaring is giving each task a date and time on your calendar instead of having the task sit on a “to-do” list. By planning in advance on your calendar, which is often muddled by various shift times, conferences, and meetings, a specific time to focus on important tasks you can make sure daily you are accomplishing mission-driven work. A survey of over 14,000 physicians showed that one of the main causes of burnout was “spending too many hours doing work.” By calendaring your day, you can be more efficient with your work and ultimately reduce your risk of burnout.21

Make a plan for each day

It is important that each day has a plan.9, 16, 22 One of the experts at mission-driven work, Cal Newport, author of Deep Work, suggests scheduling every minute of your day and making sure your plan is written down.23 Some articles in the medical literature also recommend time blocking, grouping similar activities together, such as meetings, interviews, and writing blocks.1 Make sure you have Quadrant 2 activities, those important, long-term items, in your daily plan.5 For EM educators, this may be having a 30-min time block to write every day or a 3-h block of time carved out during a nonclinical work day. It is also important to schedule downtime for rejuvenation, so put in your calendar sabbatical and vacation time as well.17 Each day should end with reviewing and preparing for the next day.

Plan your week and month

Single-day planning can be reactionary and has the potential to shunt your attention toward “urgent” but less important activities.5 This allows the “tyranny of the urgent” to shift your focus to your daily priorities and away from bigger goals.1, 24 Longer-term planning is needed to be more proactive and have a bigger vision.9 Planning for the month or year can be too vague, making weekly planning often the sweet spot.25 For EM educators, weekly planning can help us keep focus during our academic days planned around our shift schedules.

CONCLUSION

Once we have solidified our mission, we need to put in place a plan to execute it (Figure 1). By time auditing, it is possible to know where time is spent and prevent time wasters. Actualizing our mission means planning not only our day but your week or longer in advance. Given our irregular schedules as emergency physicians, this step is essential. Incorporating these practical strategies can help emergency medicine educators avoid becoming overwhelmed and stay focused on their mission-driven work.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Jennifer Kanapicki Comer: article concept and design, extensive literature search with tremendous help from Graduate/Clinical Education Librarian, Christopher Stave, MLS, analysis and interpretation of the articles found in the extensive review, drafting of the manuscript, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. Julie Cueva: analysis and interpretation of articles found in the literature review, drafting of the manuscript and review of the revisions. Lauren McCafferty: analysis and interpretation of the articles found in the literature review, drafting of the manuscript, and review of revisions. Julio Silvestre; s, analysis and interpretation of the articles found in the literature review, drafting of the manuscript, and review of revisions. Miguel Reyes: analysis and interpretation of the articles found in the literature review, drafting of the manuscript, and review of revisions. Bavani Naicker: analysis and interpretation of the articles found in the literature review, drafting of the manuscript, review of revisions. Michael Gottlieb: expert advice on article concept and design, analysis and interpretation of the articles found in the literature review, drafting of the manuscript, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. Benjamin Schnapp: expert advice on article concept and design, analysis and interpretation of the articles found in the literature review, drafting of the manuscript, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.