“Workman made noise in my room. Me kept my hands on my ears!” A diary study of spontaneous memories in 34- to 36-month-old children

Abstract

Memories of past events often come to mind spontaneously, that is, without any preceding goal-directed search process. Such memories (termed ‘involuntary’ in the adult literature) have been studied extensively in adults. However, little is known about how spontaneous recollections may appear in children's everyday lives. To date, only a single diary study has been conducted. We examined three-year-olds' (N = 51) spontaneous memories by means of parental reports in a diary study during a 2-week period. Specifically, we investigated (a) cues triggering spontaneous recall, (b) the emotions associated, and (c) potential dominance of recent events in the memories recalled. The results revealed that the most prominent cues triggering spontaneous recall were ‘objects’ (32%) and ‘something said’ (30.3%). The valence of the memories was primarily positive, and the age of the memories displayed a clear forgetting curve. Overall, the findings largely replicate the memory constraints identified in adults' involuntary recollections.

1 INTRODUCTION

When examining verbally reported memories of past events in young children, the predominant method is simply to ask the children direct questions concerning the events (Hayne et al., 2015). Young children often display difficulties responding to such questions (e.g., Dahl et al., 2015; Hjuler et al., 2023; Simcock & Hayne, 2002). Meanwhile, some scholars claim that establishing memory traces of experienced events is a late developmental achievement (e.g., Nelson & Fivush, 2004; Newcombe et al., 2007; Tulving, 2005). Hence, young children's difficulties responding to questions concerning past events (e.g., Dahl et al., 2015; Simcock & Hayne, 2002) may reflect a memory trace problem. However, to respond to questions concerning past events, more than a memory trace is needed. An effective search process for the relevant memory is also required. This intentionally initiated search leading to a memory report is conceived as strategic retrieval, also sometimes called voluntary, as opposed to involuntary, retrieval (Berntsen, 2009). For adults, the search process in strategic retrieval may be straightforward. However, for young children the search process by itself may be quite demanding, and studies assessing strategic recall (e.g., by using free-recall paradigms) have repeatedly found that performance improves with age from childhood to adolescence (e.g., Ghetti et al., 2011; Schwenck et al., 2007). Hence, young children's difficulties responding to direct questions concerning previously experienced past events may not necessarily reflect an encoding or storage problem but could also be caused by the additional cognitive load related specifically to the strategic search process per se.

At times memories of past events are retrieved spontaneously, that is, without involving a potentially cognitively demanding search process. Consider the following example (derived from the present study): A mother was buying groceries in a store together with her 3-year-old son. She asked him to find a carrot. The child smiled, grasped a carrot, and enthusiastically replied: “Are we going to the deer park again to feed the deer?” Two weeks earlier, the child had visited the deer park for the first time, feeding the deer with carrots. This example and the use of the word “again” illustrates a child recalling a previously experienced event, apparently without any deliberate retrieval effort, that is, the memory came to his mind spontaneously, presumably triggered by handling the carrot. Research on involuntary memories, the equivalent term used in the ‘adult’ literature, has shown that such memories are frequent in adults (Berntsen, 2012). Moreover, they are highly dependent on associative mechanisms when recalled (e.g., Berntsen, 1996, 2012) and characterized by brief retrieval time (e.g., Berntsen et al., 2013; Schlagman & Kvavilashvili, 2008). Because involuntary memories are primarily driven by associative processes, they are less dependent on prefrontal cortex, as evinced by brain-imaging studies conducted with adults (e.g., Hall et al., 2008; Hall et al., 2014). Involuntary recall therefore may precede strategic retrieval developmentally (Berntsen, 2009, 2012). However, surprisingly little is known about involuntary recall in children, and especially regarding to what extent children's involuntary recollections resemble those of adults.

During the past 25 years, involuntary memories in adults have been examined extensively (for a recent review, see Berntsen, 2021). This upsurge in research on involuntary memories in adults began with diary studies (e.g., Berntsen, 1996, 1998, 2009). The findings showed that involuntary recall is highly context dependent, that is, the retrieval is typically facilitated by cues in the ongoing situation, and that external cues (e.g., objects and surroundings) seem to be more frequent than internal cues (e.g., thoughts, emotions) (e.g., Berntsen, 1996; Berntsen & Hall, 2004; Mace, 2006; Schlagman et al., 2007). Further, involuntary recall is typically triggered by distinct cues, or distinct cue-constellations, specifically referring to central parts the to-be-remembered event (Berntsen, 2009, 2012). Mood at the time of retrieval may also affect the emotional valence of the memory (e.g., Blaney, 1986; Schulkind & Woldorf, 2005; Simpson & Sheldon, 2020). This is often referred to as the mood-congruent memory effect (e.g., Bower, 1981; Matt et al., 1992). In a diary study, Berntsen (1996) found that the emotional content of the participants' involuntary memories were congruent with the reported mood-state at retrieval. Several studies have also shown that the emotional content of the reported memories predominantly is positive (Berntsen, 2009), consistent with the positivity bias documented in autobiographical memories in adults (e.g., Berntsen, 2009; Walker et al., 2003). Finally, when the frequency of reported involuntary memories is analyzed as a function of their memory age (i.e., temporal distance to the remembered event), a standard forgetting curve (Ebbinghaus, 1885) has been identified, in terms of a marked dominance of memories for recent events followed by a steep decline that levels off with distance into the past (e.g., Berntsen, 2012, 2021; Berntsen & Hall, 2004).

When presented with careful instructions and illustrative examples, adults report whether they recalled their own memories involuntarily or not (e.g., Berntsen, 1996, 1998). However, this first-person perspective approach becomes a challenge when assessing ‘involuntary’ memories in children. Consequently, Krøjgaard et al. (2014) introduced an alternative term, namely spontaneous memories, operationalized as memories that are (i) verbally produced, (ii) socially unprompted, and (iii) typically environmentally cued. Following this, it was possible from an observer perspective (i.e., a coder) to assess whether the memory came to the child spontaneously.

Using an experimental paradigm, in which children were brought back to a highly distinct setting, where they previously had experienced an engaging event, Krøjgaard et al. (2017) succeeded inducing spontaneous memories in 35- and 46-month-old children. Importantly, studies based on this paradigm have highlighted the relevance of environmental cues in children's spontaneous recall (Hjuler et al., 2021; Jensen et al., 2022; Krøjgaard et al., 2017; Sonne et al., 2019, 2021, 2023; for recent review, see Krøjgaard et al., 2022). For instance, by means of looking-time analyses, Hjuler et al. (2021) showed that the specific box containing props from an experienced event appeared to serve as a memory cue for children who had spontaneous recollections at test.

However, these experimental studies do not inform us about the ways spontaneous recollections appear in the everyday lives of children; nor do they provide information about (a) the typical cues triggering spontaneous recall in a natural context, (b) their associated emotions, or (c) the temporal distribution of remembered events. Whereas few studies have documented incidents of spontaneous recollections as they appear in their everyday environment (Ashmead & Perlmutter, 1980; Hudson, 1990; MacDonald & Hayne, 1996; Nelson, 1989; Nelson & Ross, 1980; Todd & Perlmutter, 1980), to date only a single diary study (Reese, 1999) has systematically examined spontaneous memories in young children. In Reese's study, mothers of 25- to 32-month-olds reported on their children's spontaneous talk about personal past events over a specific period (from 1 day to 1 week). The results showed that spontaneous memories did occur frequently in young children's everyday life, that the memories were often triggered by physical, external cues, and that the emotional content was predominantly positive. However, it is still unclear what type of external cues typically trigger the memories, and no studies have examined whether children's spontaneous memories favor recent events and can be seen to follow a standard retention curve.

Insights into these questions may qualify, or maybe even challenge, the prevailing understanding that memories of past events are a late developmental achievement (e.g., Nelson & Fivush, 2004; Newcombe et al., 2007; Tulving, 2005). Further, relatively little is known about the impact of retrieval mechanisms in the developmental literature—in part for methodological reasons (e.g., Bauer, 2004; Lukowski & Bauer, 2014). Because very little is known concerning spontaneous retrieval as an alternative retrieval mechanism, results from diary studies on spontaneous retrieval may contribute to this literature. Furthermore, comparing results from young children to results obtained with adults may help disentangling to what extent spontaneous recall in young children demonstrate the same phenomenological qualities that have been documented in adults. Such congruence across age may imply that a spontaneous recollection is a developmental precursor to strategic retrieval prevalent in young children as some scholars have proposed (e.g., Berntsen, 2012). If, in contrast, the results reveal lack of congruence, then we may speculate, (a) whether we actually examine the same retrieval mechanism in children and adults, or (b) whether spontaneous recollections in children may be inherently different from adults' involuntary recollections. Finally, insights from diary studies on spontaneous memories in young children may have applied implications for forensic psychology by highlighting the importance of distinct cues, and by obtaining further knowledge on which cues may be most prominent for triggering memories.

1.1 The present study

In the present study we wanted to expand on the knowledge regarding phenomenological characteristics of young children's spontaneous memories. By means of a structured diary method, spontaneous memories were registered in the children's everyday environment during a two-week period. We used a modified version of a procedure originally developed for examining involuntary memories in adults (Berntsen, 1996, 2001; Berntsen & Hall, 2004; Johannessen & Berntsen, 2010). More specifically, we investigated 34- to 36-month-old children's spontaneous memories in relation to (a) cues present at retrieval, (b) mood at retrieval and the emotional valence of the memory, (c) significance and rehearsal of the memory, and (d) the age of the memory. We chose this age group for two reasons: First, the children in the study should have sufficient verbal skills to be able to state their spontaneous recollections verbally. Second, previous experimental studies have shown that children in this age group do have spontaneous recollections (e.g., Hjuler et al., 2021; Krøjgaard et al., 2017; Sonne et al., 2019, 2020), and examining the same age range as in previous experimental studies allowed for direct comparison. Based on previous research showing that memories do occur spontaneously in young children in the presence of distinct cues (e.g., Krøjgaard et al., 2017; Nelson & Ross, 1980; Reese, 1999), we expected that the children would indeed have spontaneous memories during the period in which data were collected. Further, based on evidence from diary studies (e.g., Reese, 1999) as well as recent experimental evidence (Hjuler et al., 2021), we expected that physical cues would be most prominent in children's memory reports. Moreover, we expected children's spontaneous memories to behave in correspondence with adults' involuntary memories, but because this had not been explored in previous studies, the following predictions were tentative: Consistent with previous studies of involuntary memories in adults (Berntsen, 1996, 1998), the child's mood at the time of retrieval was expected to correlate with the valence of the memory recalled. Finally, as has been found in adults (Berntsen, 1996), we expected recent events to dominate.

2 METHOD

2.1 Participants

A total of 51 34- to 36-month-old children (27 girls, Mage = 35.19 months, SD = 0.58, range: 34.1–36.3 months) participated in the diary study. The participants were all healthy and full-term children recruited from the National Board of Health. They were predominantly Scandinavian Caucasian children living in families with middle to higher SES. The parents received a gift voucher of 500 Danish kr. ($75), and the children received a small LEGO building set for participating. An additional 11 children participated but were excluded from the analysis due to parents failing to follow instructions. Written and informed consent was obtained prior to participation. The study had been reviewed by the local ethics committee at the Center on Autobiographical Memory Research, Aarhus University.

2.2 Materials

The online diary questionnaire was based on the design and procedure developed by Berntsen (1996) for adults. When introduced to the diary study, the parents received a small notebook together with a manual of how to register the child's spontaneous memories in the 14-day period. In the notebook, the parents reported key aspects of the memory to assist them when filling out the online scheme later in the evening.

2.3 Design and procedure

Over a 2-week period, the parents were asked to register a maximum of two spontaneous memories per day that their child recalled, resulting in a maximum number of 28 possible spontaneous memories per child. Following Berntsen (1996, 1998), and based on experiences from four pilots, we chose a maximum of two memories per day to make it manageable for the parents. If the child had more than two recollections, the parents were asked to report the two first occurring. The day before the diary period started, the child and the parent(s) met with the experimenter in the lab for thorough instructions. For some participants, solely the mother or the father did the reporting, whereas for others both parents were involved in the process. Importantly, all parents involved in reporting the memories had to have participated in the instruction visit with the experimenter prior to the study. During the visit, the parents were carefully instructed about what qualified as a spontaneous memory, which included the following criteria; (1) it is uttered verbally; (2) it is unprompted, that is, it is not a result of a question asked by the parents themselves or by others; (3) it typically occurs as a result of something in the child's surroundings (an object, a person, a location, an action or something said) (cf., Krøjgaard et al., 2014). The parents received thorough information about how to complete the diary, using a modified version of the two-step procedure originally developed for adults (Berntsen, 1996). In addition, the parents received a detailed manual of how to complete each item in the notebook as well as in the online questionnaire, which they were asked to read carefully in advance. The manual also served as an aid to potential doubts when completing the diary. First, the memories were to be recorded in the notebook immediately after the memory occurred. Second, in the evening the same day they should be registered and elaborated upon in an online diary questionnaire using Qualtrics (see below for details).

The rationale for applying the two-step procedure adapted from Berntsen (1996) was multifaceted. First, we took our departure point in an already well-established method which uses the same two-step procedure including a notebook with keyword phrases rating scale questions to be answered immediately at the time of retrieval to reduce the need for retrospection when filling in a more extensive memory questionnaire answered later the same day. Second, because parents of young children typically have a relatively busy life, we found it necessary that the parents were given the opportunity to complete the elaborated, online questionnaire in the evening when they probably would experience fewer disturbances. In order to assess the productive vocabulary of the children, the parents also received an e-mail with a link to an electronic version of the Danish MacArthur-Bates Communicative Development Inventory: Words and Sentences (CDI) (Bleses et al., 2008), which they completed before the beginning of the diary.

2.3.1 The notebook

The notebook served as a reminder when completing the online questionnaire later in the evening. The parents were asked to have the notebook nearby whenever they were together with their child during study participation. The notebook was relatively small (i.e., 7.4 × 10.5 cm) and could therefore easily be kept in a pocket during the diary period. When a spontaneous memory occurred, the parents should note the following information in the notebook: (1) date and time; (2) where the memory occurred; (3) the child's mood (rated on a five-point scale from very negative to very positive); (4) a literal reproduction of the child's statement; (5) number of words used; (6) possible cues triggering the memory (e.g., if a ‘teddy’ seemed to have triggered the memory, parents would write ‘teddy’ in the notebook, which would be classified in the pre-defined category as ‘objects’ in the online questionnaire, whereas ‘driving by a theme park’ would be classified in the pre-defined category as ‘location’ and ‘behaving badly’ would be classified in the pre-defined category as ‘theme’); (7) which event the child was reminded of (the original event) and; (8) whether the emotional valence of the event was positive or negative (rated on a five-point scale from very negative to very positive). All aspects should be noted immediately when the memory occurred to reduce retrospection.

2.3.2 The online questionnaire

Every evening during the two-week diary period, the parents received a text message as a reminder to fill in the online questionnaire. Access to the online questionnaire was provided via a link. The exact date and time of each participant's recordings was automatically registered in the Qualtrics database. Hence, the experimenter could monitor that all parents followed the instructions by completing the diary on spontaneous memories for each respective day. In addition, if the child did not have any spontaneous memories on the respective day, parents were obliged to answer the first question, stating: “Has your child had any spontaneous memories today?” If the answer was “no”, they were told to close the browser. If the answer was “yes”, they automatically continued to the online questionnaire. All included parents complied with the instructions.

The data used in the analysis was based solely on the responses to the online questionnaire, which was substantially more detailed than the notebook. All potential spontaneous recollections reported by the parents in the online questionnaire were carefully screened to ensure that these recollections qualified as genuine spontaneous memories, and only eligible spontaneous collections were included in the final data set (see Section 2.4 for details). In addition to the parameters mentioned in relation to the notebook, the parents were also asked to answer the following questions: (Q1) “Are you certain that your child has actually experienced the event reported?” (answered with “yes”, “no” or “do not know”); (Q2) “What cue(s) do you think triggered your child's memory?” which in the online questionnaire was answered with one or more of the following pre-defined cue-categories adapted from Reese (1999); (a) person; (b) location; (c) object (e.g., a toy, a vegetable); (d) theme (e.g., being in a specific mood, Christmas-themes); (e) action (e.g., playing, going for a walk); (f) something said (e.g., a conversation); (g) none. (Q3) “How old is the memory? Please report approximately how much time has passed since the remembered event took place”; (Q4) “Has your child previously talked about the remembered event?” (rated on a five-point scale from never to very often); and (Q5) “Do you consider the remembered event to be an important or unimportant experience in your child's life?” (rated on a five-point scale from unimportant to very important). Finally, the parents were asked to report the number of hours spent with their child on the specific day. For the days where parents reported spontaneous memories, they spent on average 8.5 h (SD = 3.67, range: 1.5–24.0) together with their child.

2.4 Coding of spontaneous memories

Because we could not know what was actually going on in the children's minds when uttering something spontaneously, and for obvious reasons could not ask the children whether they came to think of the event spontaneously or not, we considered it necessary to code the memories reported by the parents based on predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Every memory reported in the online survey was coded for its validity regarding whether it fulfilled the criteria of a spontaneous memory as defined here.

2.4.1 Inclusion criteria

Every spontaneous memory included in the analysis had to fulfill the following criteria adapted from Krøjgaard et al. (2014): (a) It is verbalized by the child; (b) It is unprompted, that is, it is not a result of a question from others; (c) It refers to a specific situation which can be both unique at a specific time (e.g., driving a train for the first time) or continuous over a specific period (e.g., opening a window in the Advent calendar every morning before Christmas). Additionally, spontaneous memories of previous conversations were included. For instance, a child had a memory about a story that his mother had told about his grandfather falling out of a boat when fishing with some friends some years ago, stating, “Grandpa fell out of the boat. Then they saved him”.

When assessing the validity of each spontaneous memory, we specifically included the following information from the online questionnaire; (i) the situation where the memory occurred, (ii) the child's utterance/spontaneous memory, (iii) the description of the original event, and, (iiii) whether the parent was certain that the event had actually occurred (yes/no/do not know). Out of the total of 698 ‘spontaneous’ memories reported in the online diary 7.0% (n = 49) answered ‘no’ and 4.7% (n = 33) answered ‘I do not know’ to the question “Is the memory about a past specific situation experienced by the child?” These memories were excluded for further coding and analyses. Subsequently, those who answered the question with a ‘yes' were asked “How certain are you that the event has actually happened?” where 0.3% (n = 2) answered that they were ‘uncertain’ and 0.4% (n = 3) answered that they were ‘very uncertain’. These five memories were also excluded. Hence, a total of 87 memories were excluded from the analysis.

2.4.2 Exclusion criteria

- Semantic ‘mind-pops’ (Kvavilashvili & Mandler, 2004): Referring to factual knowledge (e.g., utterances such as “I will soon start daycare” or “you like pineapple mom!”).

- Spontaneous preferences: For instance, a child said: “I want to watch Peppa Pig on TV!”

- Situations where the child solely uttered a description of something present: A child said: “I can turn the TV on with the remote control”,

- Habits and rituals: For instance, when getting a diaper changed, a child stated: “I lift my bottom like this when Sally changes my diaper in day care.”

- Utterances specifying whom gave the child a specific gift: For instance, a child holding a book said: “Grandma gave me this book” was not included in the analysis. This was done to rule out the possibility that the memory was based on semantic information only. However, spontaneous utterances about receiving a gift referring to a special, unique situation, were included in the analysis (e.g.,” The lady in the store gave me this sticker, because she thought I was cute”).

- Utterances involving more than one general situation: For instance, a child said; “We play a jumping-game in my day care and at the gymnastics”.

The following example illustrates a valid spontaneous memory reported by a parent: (i) Situation: “My daughter and her dad are driving while passing a farm where there's a loud noise from inside”, (ii) Child's spontaneous memory:” It is noisy inside there. Workman made noise in my room. Me kept my hands on my ears!” (iii) Original event: “There was a workman who sanded the floor at her room some time ago. She thought it was too noisy and a bit scary at the time.” The example demonstrates a 34-month-old girl who was spontaneously reminded of when a carpenter was renovating here room.

We chose a relatively conservative strategy, as we wanted to diminish the risk of including memories where the parents might have misunderstood parts of the definition of a spontaneous memory. Thus, if in doubt, the memory was excluded from the analysis. Table 1 illustrates selected examples of recollections coded as valid spontaneous memories.

| Questions and answers included when coding the memories | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| “Describe the situation in which the memory occurred” | “What did your child say when recalling the memory?” | “Which event/situation was the child reminded of?” | Cue(s) | |

| 1 | He is playing with LEGO | “Is that my cat from the university?” | That he got the LEGO including the cat when we visited the university | Object |

| 2 | My daughter and I were playing with some toys that she rarely plays with. Suddenly she finds a toy in the very bottom of the box that her grandmother gave her some time ago. (I am aware that it could be questioned whether this was actually a spontaneous memory or not, but the situation and the object were both very distinct, and something we have not talked about before) My daughter broke her leg in 2017. Her grandmother visited and gave her a gift. The figure which she just found in the box | ”Oh! Grandma gave this to me when I broke my leg. Then grandma gave it to me. A present!” | Her grandmother gave her a present because she unfortunately broke her leg | Object |

| 3 | My daughter had just finished her breakfast and her father was about to brush her hair. They talked about that the hair was not too messy and that it could easily be brushed | ”Now the hair is not red anymore. There is no more beetroot in it after washing it” | She got beetroot in her hair while eating lunch last Sunday. She had a shower at night and got her hair washed | Action something said |

| 4 | Him and I watched TV. Then Garfield came | ”Where is the red brush now?” | When we saw an episode of Garfield where he hid another character's red brush | Theme person |

| 5 | We were in the kitchen and she says that she wants to listen to Christmas music. Then she walks to the door and says “hohoho” | “Santa in the door” | Attending the music class last time, she was introduced to a new song which she obviously came to think of | Theme action |

| 6 | Mom and Dad were there and we talked about some friends that would come visit the next day | ”I will not have my hair cut, right?” | One of our friends who would visit is a hairdresser and she cut his hair last time they visited | Person something said |

| 7 | My son and I enter a grocery store. I tell him to grab a bag of carrots. He smiles happily as the memory comes to his mind | “Are we going to the deer park again to feed the deer?“ | “After the first visit at the University, we went to the deer park and brought carrots to feed them” | Object |

| 8 | We were going downstairs to change her diaper and then it came | “Grandma fell on her ass” | My mother came visit and fell downstairs hitting her ass and getting a very big bruise | Location |

| 9 | He was standing peeing at the toilet. I, mom was there too | That one fell down! And my willie and my hands got hurt | The previous night he was standing peeing and the toilet seat snaped shut | Object action |

Two independent coders coded the data. One primary coder coded all the material, and a secondary coder re-coded 20% of the randomly selected material. Interrater agreement was in the acceptable range: 86.4%, κ = 0.688, p < .001. Disagreements were solved by discussion. Out of the total of 698 ‘spontaneous’ memories reported in the online diary, we ended up with 479 valid spontaneous memories to be included in the analysis after the coding procedures.

3 RESULTS

Fifty-one parents successfully completed the online diary by following the procedure of recording their child's spontaneous memories (if any) each day over the two-week period. Overall, the children produced valid spontaneous memories with a mean of 9.02 (SD = 5.58) memories out of a maximum of 28 during the two-week diary period. A Spearman correlation analysis showed a significant positive association between the child's productive vocabulary and the number of spontaneous memories produced rs(49) = .297, p < .005.

The statistical analyses will be presented in the following order: (1) Cues present at retrieval: We analyzed which cues had triggered spontaneous memories by calculating the proportion by which each kind of cue had triggered spontaneous memories for each child and conducted an analysis by means of a one-way repeated measures ANOVA. (2) Memory valence, mood, significance, and rehearsal: We examined a possible effect of current mood on memory valence (i.e., mood congruency) by a pooled within-subjects single model multiple regression analysis. Moreover, we ran a Spearman's Rho correlation to examine the relation between the significance and rehearsal of the remembered events. (3) Age of the memory recalled: For age of the events recalled, we calculated the percentages by which the memories had occurred within the last day, the last week, the last month, and the last year. Further, a potential dominance of recent events was examined by calculating a power function fit illustrating the retention time of the memories recalled spontaneously.

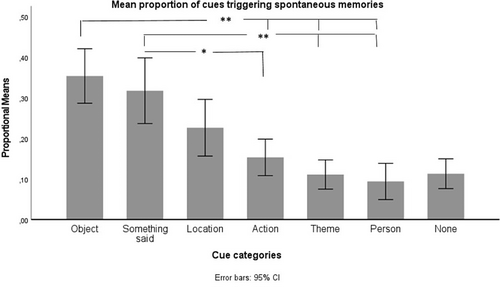

3.1 Cues

Potential cues for triggering the spontaneous memories were pre-categorized in the questionnaire. Given that a single memory could in principle be triggered by several cues, we calculated the proportion by which each cue-category had triggered spontaneous memories for each child: Proportion of the specific cue = Total N of the specific cue/Total N of memories generated by the child. Proportions were used to control for the fact that the children generated different numbers of memories. A one-way repeated measures ANOVA with a Greenhouse–Geisser correction with cue-category (person, location, object, theme, action, something said, and none) as the within-subjects factor and the mean proportions of spontaneous memories as the dependent variable, showed an effect of cue: F(3.7, 185.1) = 13.23, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.209. Bonferroni post-hoc analyses revealed that the cue-categories “objects” and “something said” were the main triggers of spontaneous memories (see Figure 1). With the exception of “location” (18.8%), both “objects” (32%) and “something said” (30.3%) triggered spontaneous memories significantly more frequently, than the remaining cue-categories combined.

3.2 Phenomenological characteristics

3.2.1 Emotional valence and mood congruency

Both mood (rated for the retrieval situation) and valence (rated for the remembered event) had been reported on 5-point-likert scales (cf. Section 2.3.2). As expected, the emotional valence of the remembered events was primarily rated as positive, M = 3.71, SD = 1.25. Likewise, mood at retrieval was also rated overall positive M = 4.18, SD = .82.

Consistent with a mood congruence effect, we observed a positive correlation between ratings of mood at retrieval and valence of the remembered events, N = 479, r = 0.284, p < 0.001. However, because the 479 individual memories were clustered around the 51 children, they could not legitimately be viewed as independent observations. Following previous diary studies (e.g., Berntsen & Hall, 2004), we therefore conducted a single model multiple regressions analysis in which each subject variable was dummy-coded and included as independent variables in the analysis (the number of dummy coded variables was N-1). The independent variables were mood at retrieval plus 50 dummy-coded variables to partial out participant variance, and the dependent variable was the emotional valence of the remembered events. With this method, each memory could be legitimately treated as an independent observation (Cohen & Cohen, 1983; Thompson, 1996). The analysis showed a clear association between the mood at the time of retrieval and the valence of the memory recalled, F (51, 410) = 2.638, p < .001, with an R2 of 0.247.

3.2.2 Memory significance and rehearsal

A Spearman's Rho correlation was conducted to assess the relation between memory significance (M = 2.45, SD = 1.43) and memory rehearsal (M = 2.14, SD = 1.20). The analysis was based on mean ratings calculated for each child. We found a significant positive correlation between memory significance and rehearsal, N = 51, rs = 0.409, p < .01, indicating that children whose remembered events were rated as more important, generally brought up memories more frequently compared to children with less personally important events, according to parents' ratings, or it might indirectly reflect that parents who reminisce more frequently with their children, place a higher value on memories in general, and thus rate memories as more important.

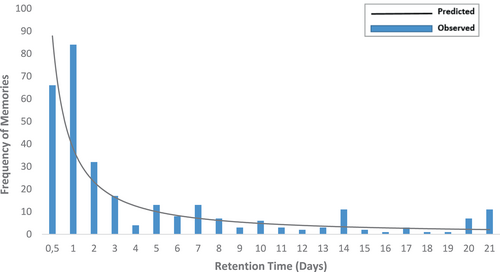

3.2.3 Dominance of recent events

As expected, a clear dominance of recent events was found (see Figure 2). About one third (33.9%) of the memories were about events that had taken place within the last 24 h, 53.5% were dealing with events from within the last week, 72.5% from within the last month, and 99.3% from within the last year. Figure 2 provides memories reported as being 0–21 days old (which accounted for 67.3%). The observed data fitted the power function formula: frequency = 87.815 (days +1)−1211, where the exponent denominates the retention gradient. The function accounted for 64% of the variance. As evident in Figure 2, there is a clear peak at 7, 14 and 21 days, probably suggesting that the parents may have rounded off to entire weeks when reporting the age of the event, thus adding noise to the estimated retention time.

4 DISCUSSION

Whereas involuntary or spontaneous recollections have been studied extensively in adults, surprisingly little is known from a scientific perspective regarding spontaneous recollections in young children. In particular, we know close to nothing concerning how spontaneous memories appear in children's everyday surroundings as to date only a single diary study has been conducted addressing this issue (Reese, 1999). The present study aimed at addressing this gap in the literature by conducting a comprehensive diary study with a dedicated focus on the spontaneous recollections as they were reported by carefully instructed parents of 51 34- to 36-month-old children.

Although hitherto largely neglected in the scientific literature, the results from the present study suggest that spontaneous recollections may be a prominent part of young children's mental life. This implies that when considering mechanisms of retrieval and their consequences (cf. Bauer, 2004), spontaneous retrieval probably calls for more attention than it has previously been granted. For instance, in many scholarly accounts, retrieval is assumed to be closely tied to the involvement of prefrontal cortex (cf. Bauer, 2004; Lukowski & Bauer, 2014). Whereas this is the case when considering strategic retrieval, it is probably not the case, or at least less important, when considering spontaneous recall (Hall et al., 2008; Hall et al., 2014).

The results from the present study showed that the young children's spontaneous memories shared many of the same phenomenological characteristics as has been documented in adults regarding (1) cues, (2) memory valence and mood congruency, and (3) dominance of recent events. Consistent with previous studies showing that external cues are indeed central in spontaneous memory recall (e.g., Hjuler et al., 2021; Reese, 1999), we found that the most prominent cue was ‘objects’. Moreover, ‘something said’ was also found to be an essential memory-cue, highlighting the important role of parent–child reminiscing (e.g., Farrant & Reese, 2000; Fivush, 2019) and social aspects of narrating about the past (e.g., Bluck et al., 2005; Nelson, 1993). The present study was the first to examine a possible association between the spontaneous memory recalled and the child's mood at the time of retrieval. Consistent with findings in adults (e.g., Berntsen, 1996; Blaney, 1986), we found a congruency between the current mood at retrieval and the emotional content of the memories. In line with Reese (1999), and the adult literature on autobiographical memory (Walker et al., 2003), the valence of the children's spontaneous memories was primarily positive, possibly reflecting a positivity bias. Finally, our results illustrated a clear dominance of recent events in the age of the memories in that most of the events had taken place within the last day.

Overall, the results from the present study show that besides being prevalent in young children's everyday lives, spontaneous memories also seem to share many of the same phenomenological characteristics that have been found in adult's involuntary memories. Together with the results obtained by Reese (1999), these results may suggest that spontaneous recall is likely to be an early developmental achievement, at least up and running early in the third year of life. The observed similarities between children's and adults' spontaneous/involuntary memories support the assumption that spontaneous recall may constitute a basic mode of remembering that is established relatively early in life, as suggested by Berntsen (2009, 2012). Although the data obtained here do not provide conclusive evidence is this regard, the findings from the present study are at least consistent with the assumption that spontaneous recollections appear early in life. This view is further supported by the results from previous studies showing that young children typically recall more details when their recall is spontaneous (i.e., in settings based on associative processes dependent on salient characteristics in their surroundings), relative to when they are explicitly asked to recall a specific memory (Todd & Perlmutter, 1980). Considering the fact, that children begin to verbally refer to past events from the second year of life (e.g., Fenson et al., 1994), spontaneous memories might be occurring in even younger children than the children assessed in the present study. In fact, very recent evidence supports this prediction, as Jensen and colleagues successfully induced spontaneous recollections in an experimental setting in two-year-olds by exposing them to unique cue-constellations (Jensen et al., 2023). Thus, future studies should assess both younger and older age-groups to expand on the knowledge regarding spontaneous memories across different ages.

The results from recent experimental studies in which spontaneous and strategic retrieval were compared across age groups have documented a striking interaction between age and retrieval mode. When recalling previously experienced events spontaneously, 35-month-olds and 46-month-olds performed at the same level. In contrast, the 46-month-olds systematically outperformed the 35-month-olds when directly asked to recall information about the same event (Jensen et al., 2022; Krøjgaard et al., 2017; Sonne et al., 2020, 2021; see also Caza & Atance, 2019; Martin-Ordas et al., 2017). Applying the same experimental paradigm, Hjuler et al. (2021) found that salient ‘objects’ present in the lab (two unique and distinct boxes) seemed to be the main triggers of spontaneous recall of the past experienced event.

In these experimental studies, however, the context was predefined, and the social interaction between the child and the parent was almost absent by design, as the parents were instructed not to say anything during the test-session, resulting in an almost non-interactive setting. Moreover, due to the controlled setting, the cues to potentially trigger spontaneous memories were not only predefined, but also relatively sparse. In contrast, in the present diary study, the context for triggering spontaneous recollections was not only richer, but also mirrored each individual child's familiar, daily life context. Further, the parent was present when registering the memories, facilitating everyday social interaction—in stark contrast to the silencing experimental setup. Interestingly, this difference was directly reflected in the results as we found that ‘something said’ occurred as a memory cue in 30.3% of all instances of spontaneous recall, almost at the same level as ‘objects’, and hence the second most prevalent cue overall. Note that this effect would not be identifiable in the aforementioned experimental paradigm where parents were prohibited engaging in conversations with their child during the testing period. Thus, the results from the present diary study directly demonstrate the importance of ‘something said’ as a prominent memory cue—even in situations where ‘something said’ is not a direct question or similar (if it had been, the memories would not have counted as spontaneous). Furthermore, diary studies allow the reporting of a variety of memories referring to different time points in the past, which enables a systematic analysis of their temporal distribution. Similar data concerning temporal distribution would be difficult to collect in experimental designs. Hence, it could be argued, that diary studies and experimental studies complement one another and when combined provide a more complete understanding of children's spontaneous memories than any single approach.

Contrary to our findings, the frequency of ‘verbal cues’ triggering spontaneous recall in Reese's (1999) study was minor. One tentative explanation might be the children's different ages and corresponding language skills. Whereas the children in Reese's (1999) study were 25- to 32- month-olds, the children in the current study were 34- to 36-month-olds, making the children in the present study more prone to engage in language-interactions characterized by dialog. This interpretation is supported by the positive association between the child's productive vocabulary and the number of spontaneous memories produced in the present study. Another possible explanation might be, that whereas the parents of the children in the present study primarily came from middle- to high-SES homes, half of the mothers in Reese's (1999) study did not have any tertiary education. Thus, since vocabulary is associated with parents SES (Hart & Risley, 1995), the children in the present study might simply be more verbally skilled for their age compared to the children in Reese's (1999) study.

A clear advantage of the present diary study is the way in which spontaneous recollections were captured in the child's everyday environment, with the presence of a multitude of potential cues. What might seem important from an adult perspective in a specific situation may not necessarily be interesting from children's view—and vice versa. By keeping record of the children's spontaneous memories as they occur in their everyday environment, the child itself is in charge of “what to pay attention to”.

One obvious limitation of the present study is the reliance of parents' reporting. The children may have had spontaneous memories that were unnoticed by their parents, and the reporting of the parents may have been biased to notice some memories rather than others. For example, fluctuations in the parents' motivation, both between parents and across study time (Nelson & Ross, 1980) may have influenced their reporting. Since we have no reason to assume that the children's spontaneous recollections varied systematically across the diary period, the somewhat skewed distribution of reported spontaneous memories across the two-week diary period may reflect that the parents were highly motivated during the first and last days of the diary period, whereas their motivation may have decreased halfway. Although we cannot rule out that the memories reported might, at least to some extent, have reflected the parents' focus and their subjective interpretations, we attempted to diminish these factors by (i) giving the parents detailed, manualized instructions prior to participation, and (ii) by coding the reported recollections using a highly conservative coding manual. A further limitation that needs to be considered is that we cannot rule out that some of the recollections reported were in fact a result of a preceding deliberate search process, and thus in nature a voluntary recollection. Obviously, neither the three-year-olds, nor their parents, are capable of making these distinctions with absolute certainty. On a related note, the number of reported spontaneous memories might have been underestimated, as they had to be verbally voiced by the child to be reported. It is well known that adults often have spontaneous memories without verbally uttering them (Berntsen, 2009).

The results from the present study highlight that young children's spontaneous memories are typically facilitated by contextual details reminding them of a previous, similar situation. This may have important practical implications. In forensic contexts, the child is typically asked about a previously experienced event in a setting that is different (i.e., court, police station, child house depending on the policy) from where the original event occurred and often has happened a while ago and therefore may require specific cues to be remembered. Although legal arguments for such policy certainly exist, the ensuing impairment of the contextual cues is not ideal from a memory perspective: The child's opportunities for spontaneous recall are seriously hampered, and the mnemonic abilities are thereby restricted to strategic recall which, as opposed to spontaneous recall, requires a top-down strategic search process, which matures later in the ontogenesis.

In conclusion, the results from the present study show that spontaneous memories are prevalent in young children's everyday lives, and that young children's spontaneous memories largely replicate the memory characteristics prevalent in adult's involuntary recollections. Last, but not least, the present study testifies how a structured diary method can provide unique and novel insights concerning young children's spontaneous recollections (i.e., ‘something said’ as a key cue; the temporal distribution), that would be very difficult to obtain by means of experimental methodology. Hence, both diary studies and experimental studies seem to be important and complementary approaches when examining young children's spontaneous memories—a fascinating, yet hitherto largely overlooked phenomenon in the developmental literature.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by the Velux Foundation (VELUX 10386) and the Danish National Research Foundation (DNRF 89). We would like to thank Cecilie Kousholt and Daniel Munkholm Møller for assisting with the diaries and Marie Nymand for coding the data. Also, we would like to thank the children who participated, and their parents for letting them participate.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors have no financial or personal relationships with other people or organizations that could inappropriately influence/bias our work. The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.