Clinical and Imaging Features of Sporadic and Genetic Frontotemporal Lobar Degeneration TDP-43 A and B

Funding: This work was supported by National Institute on Aging, P01 AG019724, P30 AG062422, R01 AG062758, U01 AG045390, U19 AG063911, U24 AG21886, R01 AG059794. National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, U54 NS092089.

ABSTRACT

Objective

Certain frontotemporal lobar degeneration subtypes, including TDP-A and B, can either occur sporadically or in association with specific genetic mutations. It is uncertain whether syndromic or imaging features previously associated with these patient groups are subtype or genotype specific. Our study sought to discern the similarities and differences between sporadic and genetic TDP-A and TDP-B.

Methods

We generated individual atrophy maps and extracted mean atrophy scores for regions of interest—frontotemporal, occipitoparietal, thalamus, and cerebellum—in 54 patients with FTLD-TDP types A or B. We calculated asymmetry as the absolute difference in atrophy between right and left frontotemporal regions, and dorsality as the difference in atrophy between dorsal and ventral frontotemporal regions. We used ANCOVAs adjusted for disease severity to compare atrophy extent or imbalance, neuropsychological tests, and behavioral measures.

Results

For some regions, volumetric differences were found either between TDP subtypes (e.g., worse occipitoparietal and cerebellum atrophy in TDP-A than B), or within subtypes depending on genetic status (e.g., worse thalamic and occipitoparietal atrophy in C9orf72-associated TDP-B than sporadic TDP-B). While progranulin mutation-associated TDP-A and sporadic TDP-A cases can be strongly asymmetric, TDP-A and TDP-B associated with C9orf72 tended to be symmetric. TDP-A was more dorsal in atrophy than TDP-B, regardless of genetic status.

Interpretation

While some neuroimaging features are FTLD-TDP subtype-specific and do not significantly differ based on genotype, other features differ between sporadic and genetic forms within the same subtype and could decrease accuracy of classification algorithms that group genetic and sporadic cases.

1 Introduction

Frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD) refers to a group of pathologically heterogeneous neurodegenerative disorders that are characterized based on the presence of abnormal protein aggregates. FTLD with inclusions containing TAR DNA-binding protein-43 kDa (TDP-43, FTLD-TDP) is typically found in ~50% of patients [1]. Based on the morphology and distribution of the aggregates, FTLD-TDP is further classified into pathological subtypes, the most common being types A, B, and C [2]. The term ‘unclassifiable’ (TDP-U) is applied to patients who do not fit within a defined subtype or present with inclusions too sparse for classification.

Patients with FTLD-TDP subtypes show similarities to each other, but also differ with respect to their clinical syndromic presentations and in their clinical and neuroimaging findings within the same syndrome. For example, TDP-A often presents with behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia (bvFTD) but can also present with corticobasal syndrome (CBS), non-fluent variant primary progressive aphasia (nfvPPA), or an amnestic, multidomain, Alzheimer's Disease-type dementia (AD-D) [3]. Those with bvFTD due to TDP-A have been shown to have a dorsal pattern of atrophy with greater severity of volume loss compared to TDP-B, which often presents with bvFTD with or without motor neuron disease (MND) [4].

Certain FTLD subtypes can occur sporadically or in association with specific genetic mutations, with a family history observed in 30%–50% of those with the disease [5]. Clinical and neuroimaging findings associated with these genetic mutations have been described. For example, patients with progranulin (GRN) mutations have an asymmetric presentation [6], while those with a C9orf72 hexanucleotide repeat expansion can have thalamic [6] and cerebellar atrophy [6] and show greater occipitoparietal atrophy compared to sporadic bvFTD [6].

Currently, it is unclear whether the described associations are genotype or subtype specific; for example, is asymmetric atrophy specific to GRN mutation carriers, or is it more generally associated with TDP-A, including sporadic cases and those with C9orf72 expansions? These distinctions are valuable not only to uncover regional vulnerabilities that are pertinent to understanding the onset and spread of particular mutations and FTLD subtypes, but to improve the accuracy of approaches used to predict pathological diagnoses in vivo. For example, it would only be appropriate to group sporadic TDP-B and TDP-B-C9orf72 into the same category of a classification algorithm if they can both be identified by the same shared traits. While post-mortem neuropathological assessment remains the mainstay for diagnosing FTLD and distinguishing subtypes, neuroimaging holds promise as a non-invasive technique that can potentially provide crucial support in identifying signature profiles for each FTLD subtype during life.

This study aimed to determine the clinico-anatomical similarities and differences between sporadic and genetic forms of FTLD Types A (sporadic, GRN, C9orf72) and B (sporadic or C9orf72). We also considered TDP-U, though by definition we expected greater heterogeneity in this group. TDP-C was excluded as it is historically exclusively sporadic; however, the authors acknowledge recent discoveries are beginning to link TDP-C with Annexin A11 aggregation [7] and in some cases with ANXA11 mutations. We hypothesized that distinct patterns of atrophy would be observed within and between FTLD-TDP subtypes demonstrating subtype and mutation specific neuroimaging features.

2 Methods

2.1 Participants

We retrospectively identified patients evaluated at the UCSF Memory and Aging Center between May 1999 and August 2019 who had completed genetic testing and were determined at autopsy to have FTLD-TDP types A, B, or U. This resulted in 83 participants (41 female) aged 40–81 (M = 62.04, SD = 8.02) at presentation. Participants underwent a multidisciplinary evaluation, including a neuropsychological battery designed to assess memory, language, visuospatial abilities, and executive function [8]. As part of their multidisciplinary evaluation, participants received diagnoses of clinical syndromes according to accepted criteria in use at the time [9-15]. Additionally, the Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI) [16] and Clinical Dementia Rating scale sum-of-boxes (CDR-SB) [17] were also acquired as measures of behavioral symptom severity and functional impairment. All assessments were conducted within 3-months of their initial diagnosis. For patients evaluated at multiple time points, we selected the earliest point that included all required data. Informed written consent was acquired from participants or their authorized representatives in adherence to the protocols approved by the UCSF Committee on Human Research.

2.2 Genetic and Pathological Diagnosis

DNA was extracted from available blood or frozen tissue samples and screened for genetic mutations associated with autosomal dominant inheritance of FTD or Alzheimer's disease, using standardized methods previously described [18]. These included mutations in the genes APP, C9orf72, FUS, GRN, MAPT, PSEN1, PSEN2, and TARDBP, with additional screening available for TBK-1 in four patients. Postmortem neuropathological examinations, conducted in accordance with previously reported protocols [19, 20], involved the application of consensus diagnostic criteria to determine pathological diagnoses [21].

2.3 Image Acquisition

T1-weighted images were available for a subset of participants (n = 54), collected on one of three scanners—1.5 T (n = 16), 3 T (n = 33), and 4 T (n = 5)—based on the scanner in use at the time of their evaluation. We used the initial scan that passed quality control assessments following the participants' diagnostic evaluation (mean interval = 1.65 months, SD = 3.97 months, range = 0–23.5 months). The acquisition parameters have been previously published [4].

2.4 Atrophy Maps

The preprocessing phase encompassed segmentation into multiple brain tissues, as well as alignment and normalization to standard adult tissue probability map templates in Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) space, which are included with SPM12 (http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm/). Subsequently, we applied modulation and smoothing using an 8 mm full width at half maximum Gaussian kernel.

To assess voxel-wise atrophy, we utilized W-scores relative to a healthy control group to account for the effect of normal variation or nuisance covariates on volumes, following protocols as previously reported [4]. Each structural image underwent a comprehensive visual quality assessment to identify and address any excessive motion artifacts, and we carefully checked the quality of the transformation to the template space. To evaluate the fit accuracy, we employed the r2 coefficient of determination at each voxel.

In each voxel, multiple linear regression was conducted with age, sex, scanner type, and total intracranial volume as covariates, using the reference group. The healthy control group consisted of 383 cognitively normal controls assessed at the UCSF Memory and Aging Center. Patient W-scores were determined as the discrepancy between observed and expected gray matter volume, divided by the standard deviation in controls ([(observed—expected)/SD]). The parameters used for estimating expected and SD in participants were derived from the control group. W-scores exhibit a mean value of 0 and a standard deviation of 1, with scores below 0 indicating lower volume compared to controls.

2.5 Region of Interest Masks

We selected regions a priori based on potentially distinguishing features that have been described for each included subtype or genetic mutation. To compare volumes of these pre-selected regions, we derived mean W-scores for either individual regions of interest (ROIs) or masks composed of a combination of regions derived from the Brainnetome atlas [22] and automated anatomical labelling atlas 3 [23] for the cerebellum. We created a frontotemporal mask, akin to the one described in Sokolowski et al. (2023) [24], by extracting W-scores from brain regions commonly affected by atrophy in bvFTD. We delineated regions of interest encompassing the prefrontal and temporal cortices, insula, and striatum (nucleus accumbens, dorsal caudate, and putamen). Notably, we grouped frontotemporal cortical regions based on whether they are more often associated with a dorsal or ventral pattern of atrophy and divided the subcortical structures and insula into ventral (ventral insula, amygdala, nucleus accumbens) and dorsal (dorsal insula, dorsal caudate, and dorsolateral putamen) regions. Additional ROIs included the thalamus, cerebellum, and occipitoparietal regions (Table S1, S3).

2.6 Asymmetry and Dorsality Indices

Previous research observed differences in asymmetry across genotypes [6] and differences in dorsal or ventral predominance of atrophy across subtypes [4], therefore we included both measures in our analysis to further understand if these differences are genotype or subtype specific. We calculated an asymmetry index (AI) as the absolute value of the difference between mean W-scores for all voxels in the right and left frontotemporal regions only (excluding the thalamus, cerebellum and occipitoparietal regions). Larger AI indicates greater asymmetry. Additionally, we computed a dorsality index (DI) by subtracting the W-scores of dorsal minus ventral frontotemporal regions. A positive DI indicates ventral-predominant frontotemporal atrophy, while a negative DI indicates dorsal-predominant frontotemporal atrophy.

2.7 Statistical Analysis

We categorized participants into different comparison groups, considering their FTLD-TDP subtype and genetic status, as well as grouping by the presence or absence of MND. We conducted ANOVAs and t-tests to assess differences across these groups for age, education, CDR-SB and CDR-Total. Accounting for differences in disease severity with the CDR-SB, we conducted ANCOVAs to compare the extent or imbalance of atrophy, neuropsychological test scores, and behavioral measures among these groups. To account for the effect of total atrophy on the degree of right/left and dorsal/ventral imbalance, we included frontotemporal atrophy as a covariate in the asymmetry and dorsality ANCOVAs. Subsequently, we performed post hoc tests on any significant findings resulting from three-group comparisons, while employing the Bonferroni method to address multiple comparisons. Categorical variables were compared by chi-square with post hoc comparison by z-tests with Bonferroni adjustment. All statistical analyses took place in R Statistical Software (v4.2.1) [25].

3 Results

3.1 Syndromic Diagnoses

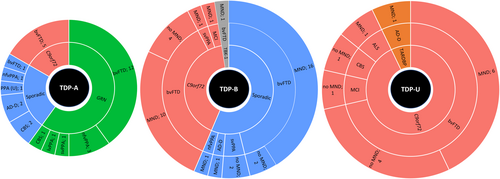

Eighty-three participants with TDP-A (n = 30), TDP-B (n = 39), or TDP-U (n = 14) were identified (Figure 1). We found no significant difference in distribution of syndromes (bvFTD compared to non-bvFTD) between TDP-A, TDP-B, and TDP-U (χ2 (df = 2, N = 83) = 5.88, p = 0.053). Within TDP-A, we found a significant difference in distribution of syndromes (bvFTD compared to non-bvFTD) between GRN, C9orf72, and sporadic, driven by the low frequency of bvFTD in sporadic cases (χ2 (df = 2, N = 30) = 9.76, p = 0.008). Post hoc tests were non-significant after correcting for multiple comparisons. No significant difference in distribution of syndromes (bvFTD compared to non-bvFTD) were found for TDP-B.

C9orf72 cases made up most of the TDP-U participants (13/14), almost half of TDP-B cases (16/39), and a minority of TDP-A cases (5/30). All 5 of the TDP-A-C9orf72 cases presented with bvFTD. People with TDP-A-sporadic rarely presented as bvFTD (1/7). No bvFTD cases with TDP-A developed MND. Of the TDP-A-nfvPPA cases, 3/4 were GRN carriers and 1 sporadic. TDP-B participants typically included MND in sporadic cases (18/22) and C9orf72 expansion carriers (12/16). MND was present in the one TBK-1 participant. All participants with TDP-U carried C9orf72 repeat expansions, except for 1 with a TARDBP mutation. TDP-U-C9orf72 was split between whether they developed MND (6/10) or not. The aim of this study was to compare sporadic and genetic forms of each FTLD-TDP subtype. Given that no TDP-U cases were sporadic, this subtype was generally excluded from further analysis. However, we included TDP-U cases for a specific comparison among C9orf72 repeat expansion to investigate whether atrophy patterns are similar among expansion carriers regardless of subtype or are distinct in TDP-U patients.

3.2 Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

Table 1 summarizes demographic characteristics, clinical variables, and the corresponding statistical differences between diagnostic groups. We found no significant differences for sex, years of formal education, CDR Total, nor CDR-SB score between TDP-A and TDP-B participants. Participants with TDP-A were significantly older at the time of their initial assessment at UCSF (M = 65) than those with TDP-B (M = 60). When controlling for CDR-SB score, we found TDP-A participants lived significantly longer from their first initial visit compared to those with TDP-B; however, no significant differences were observed for survival from age of onset.

| TDP-A | TDP-B | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | GRN | C9orf72 | Sporadic | All | C9orf72 | Sporadic | TBK-1 | |||||||||

| n | M (SD) | n | M (SD) | n | M (SD) | n | M (SD) | n | M (SD) | n | M (SD) | n | M (SD) | n | M | |

| Age | 30 | 65.07 (6.69)a | 18 | 64.06 (6.92) | 5 | 63 (2.92) | 7 | 69.14 (6.99) | 39 | 60.23 (8.45)a | 16 | 56.19 (9.01)b | 22 | 63.36 (6.9)b | 1 | 56 |

| Male (n) | 30 | 13 | 18 | 6 | 5 | 3 | 7 | 4 | 39 | 20 | 16 | 8 | 22 | 12 | 1 | 0 |

| Education (years) | 29 | 15.69 (3.24) | 17 | 15.88 (3.04) | 5 | 12.8 (3.35) | 7 | 17.29 (2.63) | 38 | 16.34 (3.02) | 16 | 15.56 (3.12) | 21 | 17.05 (2.89) | 1 | 14 |

| CDR total | 29 | 1.19 (0.84) | 17 | 1.15 (0.81)c | 5 | 2 (0.71)c | 7 | 0.71 (0.64)c | 39 | 1.51 (0.85) | 16 | 1.59 (0.76) | 22 | 1.48 (0.94) | 1 | 1 |

| CDR-SB | 29 | 6.72 (4.71) | 17 | 6.62 (4.44) | 5 | 10.6 (3.9) | 7 | 4.21 (4.59) | 39 | 8.21 (4.18) | 16 | 8.78 (3.64) | 22 | 7.84 (4.66) | 1 | 7 |

| Age of onset | 29 | 60.52 (6.29)a | 17 | 59.53 (5.46) | 5 | 57 (3.54) | 7 | 65.43 (7.46) | 33 | 53.74 (11.2)a | 16 | 46.75 (12.52)b | 22 | 58.82 (7.13)b | 1 | 54 |

| Survival years from first visit | 29 | 4.31 (2.89)a | 17 | 4.3 (3.31) | 5 | 4.34 (2.27) | 7 | 4.29 (2.5) | 39 | 2.52 (2.48)a | 16 | 2.15 (1.91) | 22 | 2.85 (2.86) | 1 | 1.29 |

| Survival years from age of onset | 29 | 9.35 (4.96) | 17 | 9.53 (5.91) | 5 | 11.23 (2.81) | 7 | 8.41 (1.61) | 39 | 9.53 (6.77) | 16 | 12.05 (8.62) | 22 | 7.97 (4.56) | 1 | 3.59 |

| NPI delusions | 26 | 0.54 (1.75) | 17 | 0.35 (1.06) | 4 | 2 (4) | 5 | 0 (0) | 35 | 1.74 (3.69) | 15 | 0.67 (2.09) | 19 | 2.37 (4.46) | 1 | 6 |

| NPI hallucinations | 26 | 0.27 (0.87) | 17 | 0.29 (0.99) | 4 | 0.5 (1) | 5 | 0 (0) | 34 | 0.24 (0.55) | 15 | 0.13 (0.35) | 18 | 0.28 (0.67) | 1 | 1 |

| NPI agitation | 26 | 1.65 (2.91) | 17 | 1.94 (3.29) | 4 | 0 (0) | 5 | 2 (2.55) | 34 | 3 (3.61) | 15 | 3.4 (3.62) | 18 | 2.83 (3.71) | 1 | 0 |

| NPI depression | 25 | 2 (2.71)a | 17 | 2.29 (3.02) | 3 | 0 (0) | 5 | 2.2 (2.05) | 34 | 0.65 (1.67)a | 15 | 0.93 (2.22) | 18 | 0.44 (1.1) | 1 | 0 |

| NPI anxiety | 25 | 2.52 (3.31) | 17 | 2.88 (3.35) | 4 | 2 (4) | 4 | 1.5 (3) | 34 | 1.94 (3.35) | 15 | 1.73 (2.81) | 18 | 1.89 (3.77) | 1 | 6 |

| NPI euphoria | 26 | 1.69 (3.15) | 17 | 2.59 (3.61) | 4 | 0 (0) | 5 | 0 (0) | 34 | 3.62 (4.19) | 15 | 3.8 (4.39) | 18 | 3.44 (4.26) | 1 | 4 |

| NPI apathy | 25 | 6.44 (4.64)a | 17 | 6.53 (4.64)d | 3 | 10.67 (2.31)d | 5 | 3.6 (4.1)d | 34 | 8.88 (2.84)a | 15 | 9.07 (2.91) | 18 | 8.56 (2.81) | 1 | 12 |

| NPI disinhibition | 26 | 3.88 (4.06) | 17 | 4.06 (3.91) | 4 | 4 (4.62) | 5 | 3.2 (5.02) | 34 | 5.35 (3.95) | 15 | 5.6 (3.52) | 18 | 5.44 (4.27) | 1 | 0 |

| NPI irritability | 26 | 1 (2.12) | 17 | 1.18 (2.21) | 4 | 0 (0) | 5 | 1.2 (2.68) | 34 | 2.56 (3.98) | 15 | 2.53 (3.96) | 18 | 2.72 (4.17) | 1 | 0 |

| NPI aberrant motor behavior | 26 | 3.77 (4.42)a | 17 | 3.94 (4.56) | 4 | 4.25 (5.44) | 5 | 2.8 (3.9) | 34 | 6.68 (4.28)a | 15 | 5.8 (4.78) | 18 | 7.44 (3.91) | 1 | 6 |

| NPI sleep changes | 25 | 2.68 (3.11) | 17 | 2.41 (3.26) | 3 | 4.67 (1.15) | 5 | 2.4 (3.36) | 34 | 2.24 (2.97) | 15 | 0.67 (1.8)b | 18 | 3.5 (3.24)b | 1 | 3 |

| NPI eating behavior | 26 | 4.5 (4.37)a | 17 | 5.29 (4.47) | 4 | 5.25 (5.12) | 5 | 1.2 (1.64) | 34 | 6.71 (4.41)a | 15 | 5.4 (4.72) | 18 | 7.72 (4.1) | 1 | 8 |

- Abbreviations: CDR-SB, clinical dementia rating scale sum of boxes; M, mean; NPI, neuropsychiatric inventory; SD, standard deviation.

- a p < 0.050 between TDP-A and TDP-B.

- b p < 0.050 between TDP-B-C9orf72 and TDP-B-Sporadic.

- c p < 0.050 main effect of gene within TDP-A ANCOVA. Post hoc p < 0.050 (Bonferroni corrected) between C9orf72 and sporadic.

- d p < 0.050 main effect of gene within TDP-A ANCOVA. Post hoc NS after Bonferroni correction.

We compared functional measures and NPI scores between groups (Table 1). Notably, hallucinations and delusions, which have been described as occurring in FTLD-TDP and these genetic mutations, were infrequent across both subtypes, with no significant differences between genetic and sporadic cases within each subtype (Table 1).

We compared performance between diagnostic groups on a battery of neuropsychological assessments including memory, language, visuospatial abilities, and executive function (Table S2). Notably, we observed no differences between TDP-A and TDP-B participants across all assessments.

To investigate any differences within bvFTD specifically, we ran the same analysis limiting only to bvFTD participants (Table S3).

3.3 Imaging Analysis

Atrophy analyses included 54 participants (25 female) aged 45–81 (M: 62.30, SD: 7.54) who had brain imaging and CDR-SB data. We ran three main comparisons: TDP-A vs. TDP-B; 3 × 1 ANCOVA for C9orf72, GRN, and sporadic within TDP-A; and TDP-B-C9orf72 vs. TDP-B-sporadic. Because there was only one case with a TBK-1 mutation within subtype TDP-B, this was excluded from all within TDP-B comparisons.

Certain differences between FTLD-TDP subtypes may reflect differences in the frequency of syndromes between genetic and sporadic groups, therefore we ran additional analyses limited only to those with a bvFTD syndrome (40 participants, 23 male, aged 45–81; M = 60.7, SD = 7.45). After applying this restriction, there was only one remaining TDP-A-sporadic participant, precluding statistical comparisons. Direct comparisons for TDP-A bvFTD participants were therefore limited to TDP-A-GRN versus TDP-A-C9orf72.

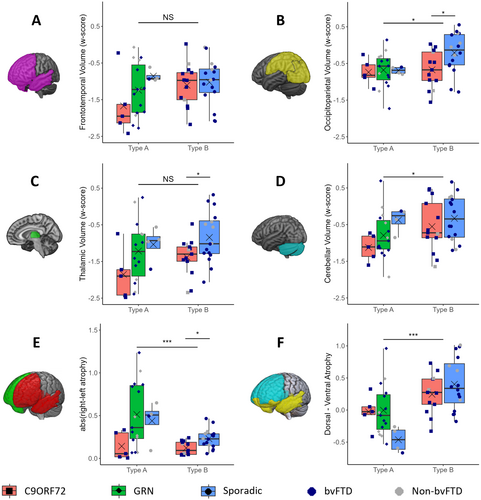

3.4 Frontotemporal

Frontotemporal volume loss was not significantly different between TDP-A and TDP-B participants when controlling for disease severity using CDR-SB (p = 0.145) (Figure 2A). While mutation carriers within TDP-A had greater overall atrophy, particularly C9orf72 carriers, these differences were non-significant (p = 0.121). We found no significant difference between genetic and sporadic groups within TDP-B (p = 0.686).

No significant differences were found when limiting to bvFTD cases only (Figure S1A).

3.5 Occipitoparietal

Participants with TDP-A presented with greater occipitoparietal atrophy compared to those with TDP-B (p = 0.027) (Figure 2B). This appears to be driven by the relative lack of occipitoparietal atrophy in sporadic cases within TDP-B, supported by TDP-B-sporadic cases showing significantly less atrophy than TDP-B-C9orf72 (p = 0.025).

When limiting to bvFTD only, these same patterns were observed; however, the differences were no longer significant (p = 0.088 and p = 0.111, respectively) (Figure S1B).

3.6 Thalamus

We found no significant difference between thalamic atrophy in TDP-A patients compared to TDP-B (p = 0.099) (Figure 2C). Sporadic cases presented with the least atrophy in both subtypes. No significant differences were found within TDP-A (p = 0.114), with a significant difference observed within TDP-B when comparing C9orf72 cases to sporadic (p = 0.029).

When limiting to bvFTD cases, TDP-A participants presented with significantly greater thalamic atrophy compared to TDP-B (p = 0.041). Sporadic TDP-B bvFTD cases again showed less atrophy than bvFTD TDP-B C9orf72 participants; however, this was not significantly different (p = 0.163) (Figure S1C).

3.7 Cerebellum

TDP-A participants overall presented with significantly greater cerebellar atrophy than those with TDP-B (p = 0.037). Across both TDP-A and TDP-B participants, C9orf72 carriers displayed more atrophy than others with the same subtype; however, these differences were not significant within TDP-A (p = 0.165), nor within TDP-B (p = 0.372) (Figure 2D).

Limiting to bvFTD cases only, the significant difference between TDP-A and TDP-B participants was still observed (p = 0.010) (Figure S1D).

3.8 Asymmetry

Overall, participants with TDP-A presented with significantly more asymmetry (absolute) than those with TDP-B (p < 0.001) (Figure 2E). TDP-A participants with GRN often showed pronounced asymmetry, including the most extreme cases, but also the greatest variance. Sporadic TDP-A cases also presented with asymmetry, whereas C9orf72 cases presented with the most symmetrical atrophy across both subtypes. No significant effect was found for gene within TDP-A (p = 0.103) while we observed significantly lower asymmetry in TDP-B-C9orf72 participants compared to TDB-B-sporadic (p = 0.004).

When limiting to bvFTD only, the significant difference between TDP-A and TDP-B remained (p = 0.005). Within TDP-A participants with bvFTD, GRN cases demonstrated non-significantly greater asymmetry compared to C9orf72 cases (p = 0.057). Within TDP-B cases, C9orf72 were again significantly more symmetric than TDP-B-sporadic (p = 0.029) (Figure S1E).

3.9 Dorsality

We observed a significantly greater degree of dorsal atrophy in people with TDP-A, as compared to TDP-B (p < 0.001). Although sporadic participants showed a greater degree of dorsal atrophy than GRN and C9orf72 in TDP-A participants, we found no main effect of gene status (p = 0.099) (Figure 2F). No significant difference was observed between TDP-B-C9orf72 and TDP-B-sporadic participants (p = 0.249).

When limiting to bvFTD only, TDP-A participants again showed a significantly greater degree of dorsal atrophy compared to TDP-B participants (p = 0.048) (Figure S1F).

3.10 Motor Neuron Disease

Within our cohort of participants identified with either TDP-A or TDP-B, only those with TDP-B had MND. In our cohort, bvFTD participants were the only subtype in TDP-B with enough participants to perform statistical analysis. Controlling for CDR-SB, although bvFTD TDP-B participants with MND had marginally less atrophy in frontotemporal regions (M: −1.1; SD: 0.59; n = 20) compared to bvFTD TDP-B participants without MND (M: −1.37; SD: 0.37; n = 4), this was not significantly different (p = 0.355). Within C9orf72 carriers, we observed bvFTD TDP-B MND participants had a similar degree of atrophy (M: −1.1; SD: 0.68; n = 8) compared to those without MND (M: −1.19; SD: 0.32; n = 3, p = 0.815). Within sporadic cases, bvFTD TDP-B participants with MND showed less atrophy (M: −1.11; SD: 0.58; n = 11) than the one case without MND (M: −1.91; n = 1) which precluded statistical analysis.

3.11 Additional Analyses

We compared TDP-A, TDP-B, and TDP-U for C9orf72 repeat expansion carriers to determine if the atypical pattern of TDP-43 pathology in the TDP-U patients is associated with distinct patterns of atrophy. Although we found no significant main effect of subtype (A, B, or U) across all six ROI comparisons, including when limiting to bvFTD only, TDP-A again showed the greatest degree of dorsality compared to both TDP-B and TDP-U. Furthermore, TDP-U presented with predominantly symmetric frontotemporal atrophy, similar to both TDP-A and TDP-B. TDP-U patients exhibited greater frontotemporal, thalamic, and cerebellar atrophy compared to TDP-A patients, with a degree of variability similar to that seen in TDP-B patients. Occipitoparietal atrophy was similar across all three subtypes (see Figure S2).

We compared TDP-A-sporadic (n = 4) and TDP-B-sporadic (n = 16) solely to ensure subtype specific findings were not disproportionately influenced by mutation carriers. Congruent with our earlier findings, we found no significant difference between TDP-A-sporadic and TDP-B-sporadic for both frontotemporal volume (p = 0.567), and thalamic atrophy (p = 0.609). Furthermore, TDP-A-sporadic again presented with significantly more frontotemporal asymmetry (p = 0.017), and a significantly greater degree of dorsality (p < 0.001) compared to TDP-B-sporadic. Conversely, the removal of mutation carriers with high cerebellar atrophy resulted in the loss of a significant difference between TDP-A-sporadic and TDP-B-sporadic in cerebellar volume (p = 0.890). Although TDP-A-sporadic presented with greater occipitoparietal atrophy, this was no longer significantly different (p = 0.103), likely due to insufficient power. As only one TDP-A-sporadic presented with bvFTD, we were unable to limit to bvFTD only comparisons.

4 Discussion

In this study, we investigated the clinical and neuroimaging features of a cohort of patients with autopsy-confirmed FTLD-TDP types A, B, and U. We identified distinct patterns of regional atrophy, asymmetry, and dorsality across genetic and sporadic variants of FTLD, indicating that both FTLD subtype and genotype influence the pattern of neurodegeneration. Independent of genetic status, TDP-A presented with more dorsal-predominant frontotemporal atrophy and greater atrophy than TDP-B in the cerebellum and occipitoparietal regions. Symmetry appears to be a specific feature of C9orf72 mutations, present across subtypes, whereas GRN carriers show a high degree of asymmetry on average, but also notable variability. Within TDP-B, preservation of occipitoparietal regions is suggestive of sporadic disease. Furthermore, greater thalamic atrophy is observed to a greater degree in those with genetic mutations, regardless of subtype. These results suggest that genetic status needs to be considered when using clinical and imaging features to predict pathological diagnosis.

The most common presenting syndrome across all FTLD-TDP subtypes was bvFTD; however, 40% of TDP-A cases displayed alternative syndromes such as AD-D, CBS, nfvPPA, lvPPA, and svPPA, reflecting the varied clinical spectrum reported in GRN carriers [26], as well as a notably low frequency of bvFTD in sporadic cases (1/7). All GRN mutation carriers presented with TDP-A pathology. More than half of TDP-B cases were sporadic (22/39), with the remainder having C9orf72 expansions and one TBK-1 mutation. While generally associated with TDP-B or less often TDP-A, nearly as many C9orf72 expansion carriers were unclassifiable according to the TDP schema as were found to have TDP-B. MND was present in over half (8/14) of TDP-U cases, and in the majority of TDP-B (31/39), regardless of genetic status, but was absent in TDP-A patients.

Prior studies have shown greater frontotemporal atrophy in TDP-A than TDP-B [4, 27, 28]. Although these subtype comparisons were non-significant in this study, we observed greater atrophy in genetic forms of TDP-A than B, particularly when limiting to those with bvFTD. GRN carriers have a fast rate of atrophy during the symptomatic phase [29]; by selecting their first scan we may not have captured the severity of atrophy they would display later in the disease course. Despite prior studies reporting C9orf72 carriers with bvFTD and minimal atrophy [30], we did not find a difference in frontotemporal volume between mutation carriers and sporadic TDP-B. In previously reported low-atrophy C9orf72 carriers, symptoms may correlate with C9orf72-specific pathological features, including RNA foci, dipeptide inclusions, and TDP-43 dysfunction, whereas on average, those with C9orf72-related TDP-B in this study may be assessed at a stage of TDP-43 aggregation. While frontotemporal atrophy is a hallmark of all forms of FTLD, we found atrophy outside of frontotemporal areas was helpful in distinguishing subtypes; as TDP-A demonstrated greater cerebellar and occipitoparietal atrophy (and thalamic atrophy in bvFTD) compared to TDP-B. Increased cerebellar atrophy in TDP-A concurs with previous research demonstrating cerebellar atrophy is associated with TDP-A pathology [6]. Recent research suggests cerebellar structural involvement may serve as a useful marker in C9orf72-related disorders, with greater atrophy in genetic than sporadic cases [31]. We observed C9orf72 cases had higher cerebellar atrophy (across both subtypes), followed by GRN mutations, with sporadics showing the least atrophy regardless of subtype; however, these differences were non-significant, perhaps reflecting lack of power. GRN carriers presented the most striking and varied atrophy in this region indicating cerebellar atrophy is not specific to C9orf72-related disorders but may be associated with both genetic mutations.

Both GRN and C9orf72 carriers are associated with small volumes in posterior regions [6, 32]. In the current study, TDP-A mutation carriers presented with similar atrophy to sporadic. Within TDP-B, sporadic cases showed markedly less atrophy than C9orf72 carriers, who had similar atrophy to TDP-A mutations. Our findings reveal preservation of the occipitoparietal regions is suggestive of TDP-B-sporadic pathology compared to other included subtypes and mutations.

Numerous studies have observed thalamic atrophy in C9orf72 carriers compared to noncarriers [32-35]. In our cohort, within both subtypes, C9orf72 carriers presented with more thalamic atrophy than sporadic cases, which was significant within TDP-B. Thalamic atrophy was also often present in GRN carriers supporting research demonstrating thalamic atrophy is not unique to C9orf72 carriers [36] but may reflect greater subcortical atrophy in these genetic variants.

We observed distinct signatures of frontotemporal asymmetry. TDP-A is often associated with asymmetry of the frontal, temporal, and parietal lobes [37]. Early research suggested asymmetry might be specific to TDP-A pathology [27]; however, subsequent studies have reported greater asymmetry in GRN carriers compared to other FTLD mutations, suggesting genetic mutation specificity [6, 38]. Our observations indicated greater asymmetry in TDP-A compared to TDP-B, primarily due to higher levels of asymmetry in GRN and sporadic cases. Consistent with previous research, GRN carriers displayed the highest levels of asymmetry but also the largest variability [39], highlighting heterogeneity in lateralization. Notably, our observations indicate that absence of asymmetry does not preclude a GRN mutation. While this study would not capture longitudinal changes in atrophy, variability in the degree of asymmetry may be attributed to shifts in hemispheric atrophy over time, supported by early work observing increased asymmetry with disease progression in GRN carriers [40]. The pathological mechanism driving the asymmetry remains unclear; however, it is possible that TDP-43 proteinopathy induced by GRN mutations interacts with pre-existing brain asymmetries, exacerbating structural perturbations [41]. Although TDP-B showed greater symmetry overall, this was significantly more pronounced in C9orf72 compared to sporadic cases (including when limited to bvFTD). This, alongside the symmetrical presentation found in TDP-A-C9orf72 mutations, suggests symmetry is a C9orf72 feature rather than specifically TDP-B, corroborating previous research demonstrating symmetric frontal, temporal and parietal atrophy associated with this mutation [6].

Increased dorsality in TDP-A compared to TDP-B cases is supported by research observing significant atrophy in dorsal regions in TDP-A [4, 28, 42]. Whitwell et al., (2012) reported atrophy in GRN mutation carriers typically affects more dorsal frontal and temporal regions [6]. We found, within TDP-A, both C9orf72 and GRN carriers displayed similar dorsality; however, GRN again demonstrated the largest variability. Sporadic TDP-A cases presented with pronounced dorsality, although no significant effect of genotype was found. Regardless of mutation status, TDP-B displayed slightly more ventral-predominant atrophy than TDP-A, consistent with prior work showing that most often there is an intermediate balance of dorsal-ventral atrophy in this subtype [24]. TDP-A inclusions are often cytoplasmic, leading to dysregulation of RNA metabolism, particularly in neurons responsible for cortico-cortical connections [43], which may explain the preferential dorsal atrophy. The upper cortical layers (II/III), which are heavily involved in dorsal cognitive networks, are especially vulnerable in TDP-A.

While the presence or absence of MND can have a striking effect on prognosis and disease course, the association of MND on extra-motor atrophy remains unclear [44]. Greater atrophy in prefrontal and temporal regions has been reported in bvFTD compared to ALS and FTD-ALS patients [45]. Although we found a trend towards less atrophy in those with MND, no significant differences were observed, supporting previous research that reported no differences between bvFTD and FTD-ALS patients for any brain region [46]. Studies showing less atrophy in those with FTD-MND may also compare to an FTD group of mixed pathological diagnoses, including subtypes with greater atrophy.

The presence of psychosis has shown potential at differentiating FTLD-TDP from tau pathology [4, 47]. Severe psychotic symptoms have been suggestive of a genetic abnormality [48] and are common in C9orf72 carriers, with rates up to 50% [49]. Additional research found TDP-B pathology to be more common in non-C9orf72 carriers with psychosis than without, suggesting that the presence of psychotic symptoms is more strongly associated with FTLD-TDP type B pathology than with the C9orf72 mutation [50]. Although we found TDP-B-sporadic scored slightly higher on hallucinations and delusions from the NPI than TDP-B-C9orf72 carriers, this difference was non-significant. Overall, we did not find evidence to support a specific association between psychotic symptoms and TDP-B pathology. In this cohort, hallucinations and delusions were infrequent across both subtypes, with no significant effect of mutation status. While the low rate and severity of psychotic symptoms compared to prior studies may suggest insensitivity of the NPI for these features, this study found no differences according to genetic status, suggesting these features may be related to pathological diagnosis.

One of the limitations of our study is the small sample size in certain groups, which reduced power and precluded statistical analysis for some combinations of subtype, genotype, and syndrome. Another limitation is the data collection timeframe from 1999 to 2019, which resulted in missing data or evolution in some clinical measures. Despite this, our research sample, from a large FTD center drawing from 20 years of study, adds valuable insight into the varied neuroimaging signatures that may help predict underlying pathology and presence of genetic mutations in FTLD.

Overall, our study demonstrated that genetic mutation status significantly influences some, though not all, clinical and neuroimaging features of FTLD-TDP types A and B, highlighting the need to account for both pathological subtype and genetic status in future classification approaches. Further research is needed to explore the underlying mechanisms driving the observed differences, in order to understand how sporadic and genetic forms interact with selective regional vulnerability to result in distinct patterns of neuroanatomic atrophy within the same TDP-43 subtypes.

Author Contributions

S.C.: writing – original draft, writing – review and editing, visualization, validation, software, investigation, methodology, formal analysis, data curation. R.S.: writing – review and editing, visualization, validation, investigation, formal analysis, data curation. A.R.K.R.: writing – review and editing, validation, resources, data curation. A.S.: writing – review and editing, resources, data curation. N.G.C.: writing – review and editing, resources, data curation. D.L.: writing – review and editing, resources, data curation. A.L.L.: writing – review and editing, resources, data curation. E.M.R.: writing – review and editing, resources, data curation. Y.C.: writing – review and editing, resources, data curation. S.S.: writing – review and editing, resources, data curation. L.T.G.: writing – review and editing, resources, data curation. D.H.G.: writing – review and editing, resources, data curation. M.L.G.T.: writing – review and editing, resources, data curation. J.H.K.: writing – review and editing, resources, data curation. H.J.R.: writing – review and editing, resources, data curation. B.L.M.: writing – review and editing, resources, data curation. W.W.S.: writing – review and editing, resources, data curation. D.C.P.: writing – review and editing, visualization, validation, supervision, methodology, funding acquisition, conceptualization, investigation, formal analysis.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the invaluable contributions of the study participant and families as well as the assistance of the support staffs at each of the participating sites. This work was supported by the National Institute of Aging (U19 AG063911, U01 AG045390, P01 AG019724, P30 AG062422, U24 AG21886, R01 AG062758, and R01 AG059794) and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (U54 NS092089).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.