Interaction between riluzole treatment and dietary glycemic index in the disease progression of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

Abstract

Objective

We examined whether riluzole treatment modifies the associations between the dietary glycemic index (GI) and load (GL) and disease progression in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS).

Methods

Sporadic ALS patients in the Multicenter Cohort Study of Oxidative Stress who completed a baseline food frequency questionnaire were included (n = 304). Interactions between baseline riluzole treatment and GI/GL on functional decline and tracheostomy-free survival were examined using linear regression and Cox proportional hazard models adjusted for covariates. Age, sex, disease duration, diagnostic certainty, body mass index, bulbar onset, revised ALS functional rating scale (ALSFRS-r) total score, and forced vital capacity, from baseline were included as covariates.

Results

Baseline higher GI and GL were associated with less decline of ALSFRS-r total score at 3-month follow-up in the riluzole treatment group (RTG) but not in the no-riluzole group (NRG). When quartile groups were used, GI second [β = −1.9, 95% CI (−4.1, −0.2), p = 0.07], third [β = −3.0, 95% CI (−5.1, −0.8), p < 0.01] and fourth [β = −2.2, 95% CI (−4.3, −0.01), p < 0.05] quartile groups were associated with less ALSFRS-r decline at 3-months compared to the first quartile group (GI < 47.2) among the RTG. Similarly, GL fourth quartile group (GL > 109.5) was associated with less ALSFRS-r decline at 3 months compared to the first quartile group [β = −2.6, 95% CI (−4.7, −0.5), p < 0.05] among the RTG. In NRG, no statistically significant differences in ALSFRS-r decline were found among GI/GL quartile groups.

Interpretation

High dietary GI and GL are associated with a slower functional decline only among ALS patients taking riluzole.

Introduction

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a neurodegenerative disease affecting upper and lower motor neurons. ALS participants taking riluzole, an inhibitor of neuronal excitability,1 demonstrated prolonged survival and slower muscle strength decline in the first controlled trial by Bensimon et al.2 A survival benefit was confirmed in the subsequent trial by Lacomblez et al.3 Another trial enrolling patients with advanced disease or older age did not find survival or functional benefits with riluzole treatment, however, the sample size was small.4 Meta-analysis of these 3 trials indicated around 3 months of survival benefit and around 17% slower rate of functional decline measured by the Norris scale.5

We recently reported that ALS patients consuming higher glycemic index (GI) and glycemic load (GL) diets had slower functional decline and longer survival.6 GI reflects the rapidity of breakdown and absorption into the circulation of a carbohydrate compared to glucose while GL reflects both GI and the amount of carbohydrate in the diet (see Methods). The subsequent letter to the editor by Benjamin Brooks raised a question about riluzole treatment and the association between GI/GL with disease progression.7 This is an important question, given that riluzole is used by the majority of ALS patients in the United States and Europe.8, 9 Furthermore, the interaction between riluzole and glucose metabolism has been suggested previously in other neurodegeneration models.10-12 Thus, we examined whether the associations between dietary GI/GL and disease progression are altered by riluzole treatment.

Methods

Participants enrolled in the ALS Multicenter Cohort Study of Oxidative Stress (COSMOS) study with sporadic ALS diagnosis (revised El Escorial13 or Awaji criteria14) and baseline Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ) (n = 304) were included in this study. IRB approval and written or verbal consent were obtained.

Demographic, neurological, and dietary data were used consistent with the previously published study.6 Age, sex, race, ethnicity, onset region, and El Escorial diagnostic certainty at enrollment were extracted. Clinical assessments were performed at enrollment and each follow-up including height, weight, body mass index (BMI), medication intake, survival status, revised ALS functional rating scale (ALSFRS-r)15 scores, and percentage forced vital capacity (FVC). Survival was further ascertained with the National Death Index search. Self-administered Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ) as described previously was used to assess usual eating habits in the past 6 months at baseline and 6, 12, 24 months follow-up visits.6 Average daily GI and GL were calculated by NutritionQuest based on Block FFQ-reported food items and corresponding values from the published international table of GI and GL.16 GI is a measure of the blood glucose-raising potential of the food compared to glucose. GI values range from 0 to 100, with pure glucose assigned a score of 100. The average daily GI among the elderly adult population in one study was around 56.17 GL is obtained by multiplying the GI by the amount of carbohydrate consumed and dividing by 100. Baseline GI/GL values were used to minimize missing data; baseline and 6-month follow-up GI/GL showed moderately strong correlations.6

Statistical analyses

Demographics, clinical characteristics, and nutrient intake

The baseline variables were summarized and compared between participants with baseline riluzole treatment (RTG) and those without riluzole treatment (NRG). Two-sample t-tests were used for continuous variables and the chi-square tests were used for the categorical variables.

Covariates

The following baseline variables were included in the adjusted linear regression and Cox regression: age; sex; disease duration (weakness onset to enrollment); definite ALS (vs probable and possible ALS); bulbar onset; and BMI. Baseline ALSFRS-r total score and FVC were also included as covariates to adjust for baseline functions.18, 19

Primary analysis

ΔALSFRS-r(0–3), baseline to 3-month change of ALSFRS-r total score, was used as the primary outcome in order to minimize participant dropouts and cross-over between groups. First, the association between riluzole treatment with functional decline was examined with a multivariable linear regression model with ΔALSFRS-r(0–3) as a dependent and riluzole groups as an independent variable, adjusted for covariates. Next, we added baseline GI/GL and the interaction with the riluzole groups. Finally, the associations between GI or GL and ΔALSFRS-r(0–3) were examined separately in RTG and NRG, adjusted for covariates. Dose–response relationships were examined using GI or GL quartile groups: GI first quartile (30.3–47.2); second quartile (47.2–49.7); third quartile (49.7–52.0); fourth quartile (52.0–61.7); GL first quartile (3.5–59.5); second quartile (59.5–80.6); third quartile (80.6–109.5) and fourth quartile (109.5–284.9).

Longitudinal modeling of the functional decline

The effect of baseline GI and riluzole group on trajectories of ALSFRS-r over time (0-, 3-, 6-, 12-, 18-, and 24-months) were examined using linear mixed effect regression. We included time, riluzole group, baseline GI or GL, time x GI or GL interaction, and covariates as fixed effects. We included subject-specific random intercepts and random slopes of time. We next performed the analysis stratified by the riluzole group to quantify the effect of baseline GI or GL on the trajectories of ALSFRS-r.

Survival analysis

Cox proportional hazard models (Cox PH) were used to determine whether the associations between GI/GL and tracheostomy-free survival differed by riluzole group, adjusted for covariates. The proportional hazard assumption was tested using the scaled Schoenfeld residuals.

ALSFRS-r and survival combined analysis (ALS/SURV)

ALS/SURV combines data from repeated measures for ALSFRS-r and survival to assign a function/survival ‘rank’ to participants. ALS/SURV ranks were calculated at 3-, 6-, 12-, and 24-month follow-ups among RTG and NRG, as previously described and summarized below.20 Briefly, the value X is calculated for each participant at each visit. If the participant is dead at the follow-up, X = −100 + survival duration from baseline. If alive, X = follow-up ALSFRS-r – baseline ALSFRS-r. At each visit, rankings were determined based on the value X, ordered from the lowest value to the highest value. The first to die will receive the lowest value X and be ranked 1; the last to die will have a lower rank than the participant with the most negative ALSFRS-R decline; and the least negative ALSFRS-R decline will have the highest rank (largest rank number).20 The associations between ALS/SURV rank and baseline GI or GL at each follow-up time point were examined with linear regression models with and without covariate adjustments, separately in RTG and NRG.

R version 4.1.3 was used for all statistical analyses.

Results

A total of 304 participants were included in the analysis, consistent with our previous report.6 Among them, 161 (53%) participants reported riluzole treatment at baseline and comprised the RTG while 143 (47%) participants did not and were included in the NRG. Baseline demographics, disease history, anthropometric measures, functional measures, and nutritional variables were comparable between RTG and NRG. (Table 1) Among the RTG, 135 participants (84%) continued the medication throughout their follow-ups. Among the NRG, 25 participants (17%) reported riluzole treatment at the later follow-up visit(s). Overall, the ALSFRS-r change from baseline to 3-month follow-up (ΔALSFRS-r(0–3)) was associated with GI or GL, adjusted for covariates as described previously.6

| Riluzole (n = 161) | No-Riluzole (n = 143) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years (SD) | 61.1 (10.2) | 62.3 (9.0) | 0.2 |

| Sex, M (%) | 93 (57.8%) | 87 (60.8%) | 0.6 |

| Race: White, Black, Other (%) | 146 (90.7%), 6 (3.7%), 9 (5.6%) | 126 (88.1%), 9 (6.3%), 8 (5.6%) | 0.6 |

| Ethnicity, Hispanic (%) | 9 (5.6%) | 10 (7.0%) | 0.6 |

| Diagnostic delay, months (SD) | 8.6 (4.5) | 9.3 (4.6) | 0.2 |

| Disease duration, months (SD) | 11.8 (4.9) | 11.8 (5.1) | 0.9 |

| Rate of progression, per month (SD) | 1.1 (0.8) | 1.2 (1.1) | 0.5 |

| Bulbar onset (%) | 52 (32.3%) | 35 (24.5%) | 0.1 |

| Definite ALS (%) | 40 (24.8%) | 38 (26.6%) | 0.7 |

| BMI (SD) | 26.8 (4.4) | 26.2 (4.6) | 0.3 |

| ALSFRS-R (SD) | 36.3 (6.2) | 36.3 (6.7) | 0.9 |

| FVC, % (SD) | 80.9 (22.6) | 79.8 (22.6) | 0.7 |

| Median tracheostomy-free survival time, months | 20.5 | 20.0 | 0.9 |

| Glycemic Index (SD) | 49.0 (4.9) | 49.8 (4.3) | 0.1 |

| Glycemic Load (SD) | 89.7 (41.2) | 89.7 (41.1) | 0.5 |

First, we examined whether riluzole treatment is associated with functional decline. We did not find a statistically significant association between riluzole treatment groups with ΔALSFRS-r(0–3) (β = 0.30, 95% CI −0.7 to 1.3, p = 0.6), adjusted for covariates.

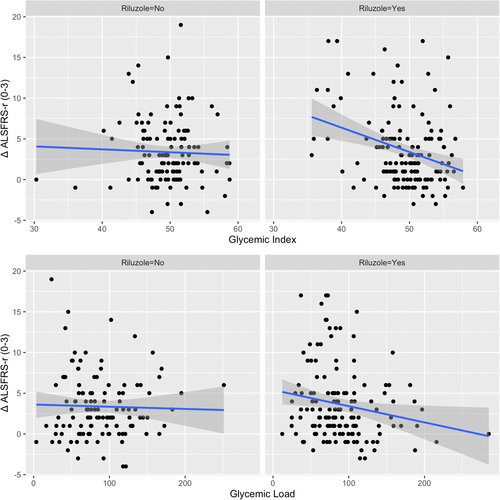

Next, we examined the interaction between riluzole treatment and GI/GL on ΔALSFRS-r(0–3). Significant interaction was found between GI and riluzole treatment (p < 0.05). Similar regression with GL revealed an interaction between GL and riluzole treatment but of borderline statistical significance (p = 0.1). These interactions are visualized in Figure 1. The differences in the slopes were apparent for both GI (coefficient − 0.3, 95% CI [−0.45, −0.24] vs −0.03, 95% CI [−0.2, 1.4]) and GL (coefficient − 0.02, 95% CI [−0.04, −0.002] vs −0.002, 95% CI [−0.02, 0.1]), with a stronger negative association between GI/GL and ALSFRS-r change among the RTG compared to NRG. When the associations between GI/GL and functional decline were examined separately in RTG and NRG groups, significant associations between ΔALSFRS-r(0–3) with GI or GL were found among RTG [GI, β = −0.24, 95% CI −0.42 to −0.06, p = 0.007], [GL, β = −0.028, 95% CI −0.04 to −0.01, p = 0.002] but not in NRG [GI, β = −0.01, 95% CI −0.18 to 0.15, p = 0.8], [GL, β = −0.0005, 95% CI −0.02 to 0.02, p = 0.9], adjusted for covariates.

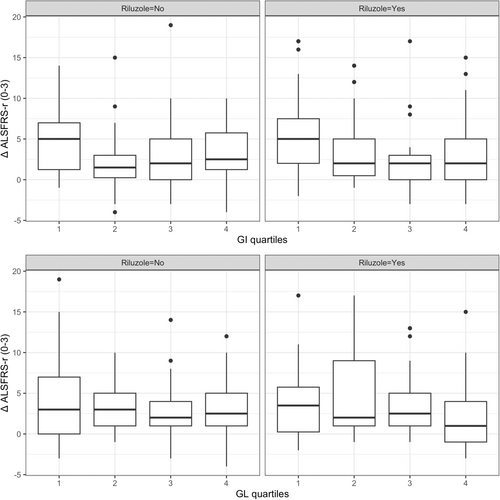

When quartile groups were used, GI 2nd [β = −1.9, 95% CI -4.1 to −0.2, p = 0.07], 3rd [β = −3.0, 95% CI −5.1 to −0.8, p < 0.01] and 4th [β = −2.2, 95% CI −4.3 to −0.01, p < 0.05] quartile groups were associated with less ALSFRS-r decline from baseline to 3-month follow-up compared to the 1st quartile group (GI < 47.2) among RTG. Similarly, GL 4th quartile group (GL > 109.5) was associated with less ALSFRS-r decline from baseline to 3-month follow-up compared to the 1st quartile group (GL < 59.5) [β = −2.6, 95% CI −4.7 to −0.5, p < 0.05] among RTG. No statistically significant differences in ΔALSFRS-r(0–3) were found between GI or GL quartile groups among NRG. (Fig. 2).

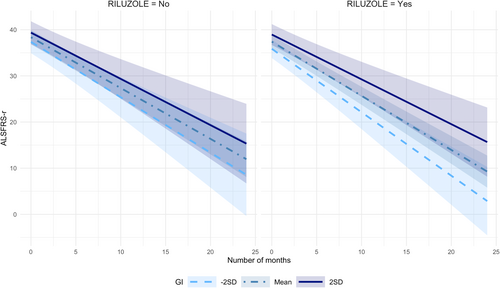

In longitudinal modeling of the ALSFRS-r declines over the 6-month follow-up period, baseline GI was associated with the slower decline among RTG [time x GI interaction β = 0.21, 95% CI 0.03 to 0.40, p = 0.025] but not in NRG [β = 0.05, 95% CI −0.13 to 0.23, p = 0.6]. Over the 24-month follow-up period, the separation of the trajectories was observed depending on baseline dietary GI. While slower slopes of decline among those with higher GI were noted in both RTG and NRG, the effect of GI on the slope was greater among the RTG. (Fig. 3) Trends of ALSFRS-r decline over 24 months were not significantly affected by baseline GL in either group.

We examined the interaction between GI/GL with riluzole treatment and tracheostomy-free survival. No significant interaction was found between GI and riluzole treatment and survival (p = 0.9) or GL and riluzole treatment and survival (p = 0.7). Higher GI was associated with longer survival in both RTG [HR 0.94, 95% CI (0.89 to 0.98), p < 0.01] and NRG [HR 0.94, 95% CI (0.89 to 0.99), p = 0.03] in unadjusted Cox PH. When adjusted with covariates, GI was no longer significantly associated with tracheostomy-free survival in either group (p > 0.05). This result was consistent when 25 participants who later started riluzole treatment were included in the RTG. GL was not significantly associated with tracheostomy-free survival in either RTG or NRG (p > 0.05), with or without covariate adjustments.

In combined outcome analysis, baseline higher GI was significantly associated with better ALS/SURV rank at 3-month (β = 2.3, 95% CI [1.0, 3.6], p < 0.001), 6-month (β = 3.7, 95% CI [1.2, 6.1], p < 0.001), 12-month (β = 2.2, 95% CI [0.8, 3.6], p = 0.002), and 24-month (β = 1.9, 95% CI [0.3, 3.1], p = 0.02) follow-ups among RTG. After adjusting for covariates, the association remained significant at a 3-month follow-up but no longer significant at later periods. Among NRG, a significant association was found between baseline GI and ALS/SURV rank at 12-month follow-up only (β = 1.9, 95% CI [0.3, 3.4], p = 0.02). However, this was no longer significant after adjusting for covariates. Baseline higher GL was significantly associated with better ALS/SURV rank at 3 months (β = 0.21, 95% CI [0.06, 0.36], p = 0.005) but not at 6-, 12- or 24-month follow-ups among RTG, after adjusting for covariates. Among NRG, no significant association was found between baseline GL and ALS/SURV rank at any time point.

Discussion

We observed that the associations between dietary GI/GL with functional decline were significant among ALS patients receiving riluzole treatment but not in those without riluzole treatment. The effect sizes of higher GI on ALSFRS-r change from baseline to 3-month follow-up, either as continuous or categorical variables, were numerically larger in the riluzole subgroup compared to the entire cohort. Compared to the lowest GI quartile, higher quartile groups (GI >47.2) had 1.9 to 3.0 points less decline in the riluzole subgroup while the differences were 1.6 to 2 points in the overall cohort.6 Considering that riluzole treatment is not significantly associated with a functional decline in our dataset, the above findings suggest that riluzole and a high GI/GL diet might reduce functional decline synergistically in the early disease course.

High dietary GI was consistently associated with slower decline beyond 3 months follow-up, among those treated with riluzole. The slopes of functional decline were significantly slower with higher GI in both groups while the differences were larger in the riluzole group. Interestingly, those with low GI in the riluzole group appear to have progressed faster than those with low GI and no-riluzole treatment. This needs to be interpreted with caution as patients were not randomized to riluzole treatment and those with more aggressive disease might have chosen to take the medication or be prescribed medication by the provider. Tracheostomy-free survival and combined survival/function outcome also suggested the benefit of high GI in the riluzole group, however, the results were no longer significant after adjusting for covariates. This might be due to inadequate sample size, a change of riluzole treatment, or dietary GI over a longer duration of time.

The mechanism underlying the potential synergy between riluzole and a high glycemic diet is unknown. The proposed mechanism of action of riluzole is through inhibition of glutamate release from the presynaptic nerve terminal which reduces the excitation of the motor neurons.21, 22 Interestingly, a previous study demonstrated that riluzole increases the glucose transport rate and up-regulates the translocation of glucose transporter to the plasma cell membrane in human motor neuron-like cells and rat myotubes.11 Among ALS patients, riluzole treatment has been associated with less weight loss further supporting the effect of riluzole in suppressing neuronal hyperexcitation and improved utilization of glucose.23 In a phase 2 clinical trial of riluzole in Alzheimer's dementia, riluzole treatment was associated with better preservation of cerebral glucose metabolism.12 These findings collectively suggest that the protective effect of riluzole and a high glycemic diet might be through energy and glucose metabolism.

In addition to previously reported limitations,6 the current analyses were further limited due to the observational nature of the study such as non-random treatment assignment and cross-over between treatment groups, and smaller sample sizes in the riluzole and no-riluzole subgroups which might have affected the survival analyses in particular. The recent observation that average blood glucose level is not associated with disease progression highlights our incomplete understanding of glucose metabolism and ALS pathogenesis.24 A randomized controlled trial incorporating a biomarker such as continuous glucose monitoring is needed to decisively examine the impact of dietary glucose in ALS.

We conclude that high dietary GI and GL are associated with slower functional decline in sporadic ALS patients taking riluzole and that nutritional counseling and dietary modification might help maximize the benefit of this drug.

Acknowledgments

We deeply appreciate the effort of COSMOS investigators (Appendix C) and study participants who contributed to generating the data used in this study.

Author Contributions

1) Conception and design of the study: IL, HM, PF, JWN 2) Acquisition and analysis of data: IL, HM, SL, JWN 3) Drafting a significant portion of the manuscript or figures: IL, HM, SL, EK, MR, PF, JWN.

Conflicts of Interest

IL, HM, SL, EK, MR, PF, JWN: Nothing to report.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.