Intersection of Social Image and Physical Space in a Former Tea Plantation Workers' Tenement: Through a Case of a Village in Sri Lanka

Funding: The author received no specific funding for this work.

ABSTRACT

This study examines the interaction between social images and actual space in tenement houses, locally called line houses, on a tea plantation in Sri Lanka. The social image of line houses was analyzed based on the discourses of managers, supporters, and residents, while tracing the history of tea plantations and its social development. The physical characteristics and space of line houses were clarified following a field survey in a village, a former tea plantation in Kandy District. Line houses have been conventionally understood only in one aspect, as poor and inhuman living environments that need to be improved or eliminated. However, the results of this study show that the line houses have acquired a sense of place and inherited Tamil culture. This finding reinforces the recent discourse that attempts to reconsider the space of tea plantations from the perspective of the people who have lived there and may provide a basis for rethinking the government's policy of resettling people in line houses.

1 Introduction

1.1 Background and Objectives of the Study

Tea plantations, which have supported the development of Sri Lanka, a country with high social security standards in South Asia, have faced changes in recent years. The bonds between space and the social organization of plantations that have kept workers in place have loosened, and the selectivity of workers' living place has increased. It is no longer unusual for plantation-born workers to leave the plantation to find work outside.1 There is a complex interplay of factors, including changes in postindependence plantation management, the restoration of plantation workers' rights as citizens, and the decline of competitiveness of the Sri Lankan tea industry in the global market.

Tea plantations were introduced in the late 19th and early 20th centuries during the British colonial period (1815–1948). There are now 453 plantations throughout Sri Lanka, most of which are located in the mountainous areas in the center of the country.2 The plantations are inhabited by Tamils who migrated from South India as laborers after the introduction of tea plantations.3

The people of Sri Lanka widely have a positive image of proud tea plantations and a beloved tea culture. On the contrary, the tenement houses (Figure 1) which are called “line houses” in local and the dwellings of Tamil laborers who have supported tea production are often associated with a negative image, and their problematic nature has often been pointed out. Sustainable development of the tea industry recently became an important political issue, and it is also involved with the formation of a social image of tea plantation line houses.

Government agencies were in a celebratory mood as Sri Lanka's tea industry marked its 150th anniversary. In this context, an independent think tank which also influences national policy stated “This house is not a home” [5], referring to the lack of rights and dignity in line houses of tea plantations. This statement is not malicious in itself as it is an assertion that the rights and dignity of the people on the tea plantations should be protected. However, this view which could be seen as a denial of the existence of life and humanity in the tenements was openly expressed. What does this mean to the people who have lived in line houses?

Sri Lankan tea plantations have often been described by analogy with “prison-like enclaves” [3] or “enclaves” [6] because of their isolation and self-contained nature. In contrast to Indian tea plantations such as Darjeeling which are described as “living and live-in imperial formation” or “a living aggregation of plants, animals, people, and nonliving materials” [7], Sri Lankan tea plantations are represented as nonliving and nonhuman spaces. In addition, the workers' homeland has been perceived as their roots in the villages of South India. Thus, the tea plantation workers have been viewed as a kind of stereotype, that is, as beings trapped in a social cage. In recent years, some studies [3, 4] have criticized that the stereotype makes them even more incomprehensible.

This study traces the ongoing debate on the complex history of tea plantations in Sri Lanka and focuses on line houses, which have been discussed only as the subject of management. This study attempts to describe the line houses that remain on the old tea plantation as a place where life and nonlife, humanity and inhumanity intersect and to reconsider the people who live in the line houses as subjective beings. Specifically, this study will cross-refer the spatial planning of the line houses, the social image of line houses formed by the discourse, and the living space of the line houses as an entity. The line houses of tea plantations are places where the voices of people of various scales and positions resonate with each other. The aim of this study was to clarify the actual state of the relationship that is created when the social image of line houses and the lives and history of the inhabitants intersect, mainly from the physical and spatial aspects of the line houses.

1.2 Previous Studies and the Position of This Study

Many studies have been conducted on tea plantations in Sri Lanka from various perspectives, including the developing process of tea plantations in Sri Lanka [8, 9], the social structure of plantations [10-12] and social issues related to education, caste, gender, and identity [3, 6, 13-15].

On the other hand, although the housing environment is one of the important issues in the social development of tea plantations promoted by the Sri Lankan government and international aid organizations, there has not been enough research from the viewpoint of workers' housing environment. In contrast to the “bungalow,” housing for the manager, research on line houses has been limited to studies that overview their spatial characteristics and the actual situation of housing supply on the plantations [1, 16]. This is probably due to the fact that the people who have lived on tea plantations have not been able to talk about their own circumstances due to various restrictions.

In this context, recent studies by Gunetilleke et al. [17] or Jegathesan [4] deserve special mention because they view the tea plantation tenement not only as a physical object, but also as a psychosocial object related to the presence of workers. Inspired by these recent studies, this study is also unique in that it attempts to view and understand the line house as a physical and spatial construction as well as a psychosocial one.

1.3 Research Method and Structure of This Paper

Chapter 2 reviews the evolution of environmental improvement on tea plantations with particular attention to the treatment of workers' housing conditions using the existing literature. It confirms the fact that plantation workers have continued to be tossed about by repeated changes in the management system and that the issue of their housing has always been an afterthought in the national social security system.

Chapter 3 explores how the social image of the line houses has been formed, referring to the spatial planning of tenements in manuals published for tea planters and the discourse surrounding line houses from the standpoints of both managers and inhabitants. This chapter will also mention “uru,” an important concept in the formation of Tamil subjectivity.

Chapter 4 examines the meaning of the line houses for the inhabitants based on a field survey in Village A, a former tea plantation in Kandy District, Central Province. It explores how the living space of the line houses as an entity is formed through inhabitants' daily practices such as building additions, renovations and maintenance and discusses the relationship between the formation of people's subjectivity and their dwelling.

2 Housing for Workers on Tea Plantations in Sri Lanka

2.1 Space and Society of Tea Plantations

In 1840, the British Sri Lankan government enacted the land act to promote plantation development. Under this law, all unregistered land was regarded as a target for seizure by the government. The confiscated land was sold to British planters for the development of plantations.4

Tea plantations were established by clearing forests in the mountainous central region of the island and are inhabited by managers and laborers. They engaged in tea cultivation and production throughout the year. Therefore, in addition to the facilities necessary for tea production, production and processing factories, administrative offices, warehouses, and storage facilities, etc., the plantations were also equipped with various functions necessary for the daily lives of the managers and workers: housing, medical care, education, religion, etc. Furthermore, these spaces were combined with the social organization of the plantation for the purpose of efficient management of tea production. As a result, the tea plantations were formed as a self-contained community that is isolated from the Sri Lankan society. A tree-like labor management system was established, with a British manager at the top and management assistants, called “kangani” following the Tamil laborers at the bottom. Hierarchical relationships were strengthened, and horizontal human relations within the hierarchy were divided.5

This hierarchical differentiation of relationships was not only in terms of organization and social structure, but also in physical and spatial aspects such as housing arrangements, clothing, and daily practices. For example, the English manager's detached house with a garden, called a “bungalow” was located on a small hill in the center of the plantation, from which he could constantly monitor the surrounding tea plantations and the line houses. The line houses within the plantation were supplied according to caste. The higher caste workers were allowed to live near the administration office or the administrator's bungalow in the center of the plantation.6

2.2 Changes in Management Systems and Workers' Housing

When tea plantations were first established, the workers' dwellings were temporary structures made of wood and earth.7 With the development of plantations, they were transformed into permanent structures made of stone blocks, bricks, iron sheets, and other materials. It is assumed that there was a certain degree of commonality in the architectural specifications of tenement buildings from that time due to restrictions on material availability and the transmission of know-how among plantations. However, plantations in the British colonial period were the private domain of owners, and the specifications of tenement houses were basically in accordance with their intention.

After independence in 1948, plantations were nationalized, and after the land reforms of 1972 and 1976, interventions such as social welfare programs and housing improvements were carried out mainly through public corporations such as Janatha Estate Development (JEDB) and Sri Lanka State Plantation Corporation (SLSPC). Housing reform involves the supply of new housing and the improvement of existing housing. Housing called “cottages,” a type of two-unit house, was also provided. In some cases, tenement houses were divided and used as multiple cottages.

In the early 1990s, JEDB and SLSPC were privatized, and the management of most plantations was transferred to newly established organizations called Plantation Restructuring Unit (PRU) and Regional Plantation Enterprises (RPEs). In addition, a nonprofit organization called Plantation Housing and Social Welfare Trust (PHSWT) continues to promote a program to improve the housing environment and social welfare of plantations. Under this program, self-help construction and improvement of housing were carried out in about 120 plantations, and a total of about 6000 housing units were provided. The Aided Self-help Housing (ASH) program was being promoted by the newly established National Housing Development Authority (NHDA) nationwide at the time. It was partially applied to the plantations, and core housing was also achieved in some of the plantations.

Thus, there have been attempts to improve the living environment, especially since the start of public intervention in plantations after the land reforms of the 1970s. However, it is said that their expansion and effectiveness have been limited.8 About 56.1% of plantation workers still live in line houses built during the British colonial period [18]. The construction of workers' line houses on plantations was prohibited by law as early as 1950 in order to eliminate overcrowding and prevent epidemics. However, the improvement of plantation housing was not a priority in the housing supply and housing environment improvement projects that the government promoted nationwide during the 1970s and 1990s. As a result, mere housing was built to replace the tenement houses in the tea plantations.

While the provision of housing on the plantations may have been important in terms of restoring workers' agency and dignity, it also involved sensitive issues. There was a distrust among Sinhalese landless farmers around Kandy that their land belonged to the plantation Tamils, as they were aware that they had been deprived of the land they had inherited from their ancestors during the British colonial period.9 It is assumed that these sentiments also had an influence on the delay in the supply and improvement of housing on the tea plantations.

2.3 Social Development and Resettlement Programs

Since the 2000s, following the end of a civil war that lasted nearly 30 years in Sri Lanka, the government has led social development of tea plantations. This was due to the enactment of law no. 35 granting citizenship to persons of Indian origin in 2003, prior to the end of the civil war, which allowed the restoration of citizenship to Tamils on the plantations. In addition, there was a problem of a shortage of labor force due to a decrease of full-time workers on the plantations and the departure of young people from the plantations. The social development of the plantations includes various projects such as education, welfare, and housing improvement, in which foreign governments, international aid organizations, and NGOs/NPOs participate in addition to the relevant ministries and the plantation development corporation. The sustainable development of the tea industry is now aimed at under the recent international humanitarian standards such as MDGs and SDGs.

As mentioned above, the improvement of housing on plantations has been an afterthought in national housing policy. However, in response to the recent trend, the government has launched a new housing supply program called the New Life Housing Program. This program aimed to supply approximately 189 000 detached houses with a dwelling area of 550 ft2 (about 51 m2) and a site area of 7 parch10 over a 5-year period. In existing tenement houses, a family lives in a dwelling unit of about 200 ft2 and residents compensate for the lack of space by sharing the land around their houses. On the other hand, it is also pointed out that unregulated land use is one of the causes of landslide disasters. The government has prepared a resettlement plan called the Cluster Village Model from the perspective of improving the living environment and disaster prevention. By 2016, it had achieved its initial goal of providing approximately 30 000 housing units. However, due to political turmoil since the 2010s, the plan has not progressed and “broken promises”11 are said to have become normal.

3 Formation of the Image of Line Houses on Tea Plantations

3.1 The Image of Line Houses in the Specifications of Architectural Plans

Tenement houses of plantations are called “line house,” “line room” or simply “line” because of the shape of one or two narrow dwelling units arranged in a line. In the colonial period, it was also called “coolie line.” Coolie means a laborer engaged in harsh and exploitative labor, and plantation workers were also referred to as such in colonial times.12

Current government plans emphasize the inferiority of the living environment of line houses. What were the original plans and designs of the tenement houses at the time of their construction? There are no uniform standards that could be found. The reason is perhaps that the planning of various facilities including the housing within the plantation was determined at the discretion of the plantation owner. However, manuals for planters were published in the private sector. These manuals seemed to be referred to in the planning of plantations and may have influenced the specific form of line houses.13 According to the manuals in the archives of the Ceylon Tea Museum, the main objectives of plantation planning were the proper management of the workers and the efficient production. This is reflected in expressions such as the plantation as “a self-contained unit” [20], which refers to the combination of the production system with space and organization, and “healthy surroundings” [22], which refers to attention to workers' sanitation.

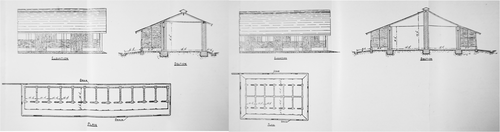

The manual also describes the specifications of the line houses with examples of drawings (Figure 2, Table 1). The common specifications among the manuals are the concept of site selection, the layout of the dwelling (building orientation within the site, distance between buildings), the choice of building structure and materials (thick stone exterior walls, tin roofing material), room dimensions (10 ft. × 12 ft. or 12 ft. × 12 ft), and veranda space (half-room to prevent rain, wind, and moisture from entering the room), and facilities for ventilation and drainage (ventilation openings, pavement), taking care of the unique conditions of highlands (slope, strong wind, cold weather) [20, 22].

| Manual 1 | Manual 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| E. C. Elliott and F. J. Whitehead: Tea Planting in Ceylon, 1931 | R. Garnier: Ceylon Rubber Plantation Manual, 1919 | |

| Concept |

|

|

| Site selection, building layout |

|

|

| Building shape, structure and materials |

|

|

| Ventilation, drainage and facility |

|

|

| Maintenance and management |

|

|

The following are also detailed descriptions of the maintenance and care of the tenements: painting pillars or doors and repainting plaster walls twice a year to prevent termites; hiring a cleaning crew to clean the area around dwellings every day; prohibiting cultivation and construction of livestock sheds nearby the tenement to keep the soil strong; and installing a latrine to keep the soil free from contamination and to prevent epidemics [22].

The manual has only a very brief description of a “bungalow” which is the residence of a plantation owner or manager. As mentioned above, the manual provides a wide range of detailed instructions for the maintenance of the line houses. Surveys of tenement housing in the 1880s reported poor living conditions and management.14 However, from the manuals, it can be seen that the planters were quite concerned about the maintenance of the workers' living environment, although it is necessary to consider that the manuals were only intended for management from the planters' perspective.

3.2 Line Houses as Objects to Improve and Eliminate

Currently, the ministries in charge of tea plantations and NGOs/NPOs are promoting the social development of tea plantation communities. As described in detail below, the dominant discourse among them is that the tenement house is an object to be improved and eliminated for the sustainable development of the tea industry. In addition, such a view is based on the image of the tenement as not only a physically degrading environment but also as a space lacking dignity and dehumanizing.

The ministries responsible for social development of tea plantations have so far prepared several action plans such as NPA 2006–2010 [24], NPA 2016–2020 [25], with the support of the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). In the action plans, line houses are described as very dilapidated stock, inappropriate for human habitation (Reference [25, p. ix]). Subsequently, new plans for the housing to replace the tenements were launched one after another, with little progress in achieving their goals. Even in those plans, the expression that line houses are inadequate and dwellings that lack pride is repeated. “These settlements from their beginnings were therefore among the poorest segments of the population of the country and were barely able to be sheltered from the vagaries of the elements” (Reference [25, p. 54]). Furthermore, the website of the Plantation Human Development Trust, an organization that promotes resettlement from tenements, showed dilapidated and defaced line houses with black-and-white images contrasted with cleans and bright detached housing on resettlement areas with color images, further emphasizing the negative image of line houses.15

In addition, on the 150th anniversary of the tea industry in Sri Lanka, the Center for Poverty Analysis (CEPA), an independent Sri Lankan think tank, expressed the view that “This house is not a home” referring to the line houses on tea plantations [5]. Citing the fact that many tea plantation workers have never even lived at an address with their name on it, CEPA denounces the government's negligence of social development on tea plantations. Unlike the ministries that oversee the tea plantations, CEPA seems not to be concerned with the sustainable development of the tea industry or ensuring profits but is instead committed to protecting the dignity and rights of workers. However, the same can be said of the line houses, which are also associated with the image of housing that is inhuman and lacking in dignity.

This social image of line houses may be common among those involved in the social development of tea plantations. Jegathesan [4], although she herself cannot accepts it, refers to the following statement by a local NGO worker involved in the social development of tea plantations. “The line room is like a prison! Only when you leave you see the disadvantages of living there. You cannot grow-socially, mentally, physically—it is a debilitating system. You can give someone a house, but will it be a space where he or she can grow or will it just be a facility?” (Reference [4, p. 99]).

3.3 Line Houses as Existence With People

On the other hand, there are discourses that focus on the improvement of the line house by the residents themselves. These affirm the existence of life and human space in the line houses. Furthermore, reflecting the complex history of plantation workers, the instability and unevenness are the essence of the line houses, and they present an image of the line houses as an existence that is always accompanied by contradictions and conflicts.

Gunetilleke et al. [17] report the reality that the smallness and inadequate facilities of the plantation tenements are being improved through the self-help efforts of the residents. They also point out that the residents feel they have the right to claim access to better housing and land ownership from the plantation management because the government and plantation owners have overlooked the problem and left tenement improvements to the residents (Reference [17, p. 41]). The existence of line houses represents “the tensions caused by the different perspectives and motivations of the labor force and the management are particularly manifest with regards to housing. The residents take the position that it is their home therefore they have the right to decide how they live and work, while the management takes the position that housing on the estates is workers' quarters requiring at the minimum the employment of at least one household member on the estate. Both positions are equally legitimate, but contradictory” (Reference [17, pp. 52–53]), and they point out the ambivalence of the line house and the contradictions that arise from this.

Jegasesan [4] focuses on the activities of investing in and renovating the line house where the residents in tea plantations regard as their “home.” She attempts to disprove the common belief that Tamils in tea plantation do not have a sense of belonging to the land in Sri Lanka. For her, the line houses are “material evidence of the uneven nature of landlessness for marginalized agricultural and migrant laborers” (Reference [4, p. 102]). The cracks in the tenement walls and the traces of generations of repairs are material “assemblages” that show investment and valorization by the inhabitants (Reference [4, pp. 115–116]). Line house dwellers perform rituals in their homes, prepare meals and eat together. Life in the tenement is always precarious and uneven, yet such a fluid structure is both a sign of alienation from society and of social connections in the tea plantation (Reference [4, p. 116]).

Bass [3] also emphasizes the fact that the ethnicity of Tamils of plantations has developed through their interaction with the dominant discourse on ethnicity in Sri Lanka. He argues that attention to the connections, however limited, between Tamils of plantations and the wider world is essential to resisting and breaking away from tea plantation stereotypes of “prison-like enclaves” (Reference [3, p. 44]).

Jegasesan [4] and Bass [3] affirm the existence of life, human space and connection to the outside world in the line house and they argue that the concept of “uru” (r) also exists in the plantation. Such a claim contains political implications. Jegasesan [4] questions the government and aid workers telling tea plantation people, who have lived in and invested in tenements for generations, that this house is not home. The assertion that there are “uru” on the plantations makes visible in society the presence of Tamils on tea plantations as a minority in Sri Lankan society, which has prospered in exchange for their labor exploitation (Reference [4, p. 124]).

3.4 Dwelling as an Extension of the Body: The Concept of Uru

The Tamil word “uru” (r) is sometimes translated as home, village, home town, etc., but its meaning differs depending on the context and is said to be a concept involving a more complex semantic system and social status.

Tamil anthropologist Daniel, born in southern Sri Lanka, describes uru as (1) a territory inhabited by people who believe they share a substance of that land and (2) a territory in which Tamils can orient themselves by recognizing it (Reference [26, p. 63]). In Tamil culture, uru is always understood in context. It is understood not only in the human context of life and family, but also in the nonhuman context involving material things such as houses, soil, water, and food. “The r can have an effect on its inhabitants, just as the planets have an effect on humans and deities have an effect on their devotees. For this effect to be accomplished, there need be no ingestion of food or water. Persons affect the substance of the ur simply through their residence in the ur and also through the combination of their food and water leavings, their bodily wastes, cremated and buried bodies, and so forth, all of which mingle directly with the soil of the r” (Reference [26, pp. 84–85]). Uru is a “fluid sign” [26] that is manifested by the intermingling of human and nonhuman in such a way that mutually shapes the nature of man and land.

In contrast to Daniel's enclosing uru, Mines called “disclosing uru,” the way uru is constituted across boundaries of caste, community, and power. Uru is a “motile discourse” (Reference [27, p. 200]), in which people and uru share a substance of soil, which is not just a metaphor but a substantive exchange (Reference [27, pp. 203–204]). The concept and substance of uru have been examined through other specific situations, and the understanding of uru continues to expand, including idealized uru [28], place naming, and uru [3] and attachment to memory in uru [29].

These diverse contexts and semantic understandings that address uru are themselves characteristic of it. That is, the characteristic that the relation to the land of a certain nature is always interpreted as the intelligence or being of a person. This identification extends not only to man and land, but also to field, temple, house, kinship, and family (Reference [27, pp. 202–203]). Because they are inextricably linked, uru has no absolute boundaries and is associated with the formation of the self. Therefore, uru is defined in the first person (Reference [26, pp. 70–71]) and “What is your uru?” has significant implications for self-disclosure for Tamils (Reference [26, p. 102] and Reference [3, p. 101]). What emerges through the concept of uru is the “person-centric orientation” of Tamil culture, which is said to be rooted in a Hindu sense of reality (Reference [26, pp. 70–72]). Each person has his or her own proportions and moderate balance in mixing with the substances of the soil. Thus, uru is always a peculiar and shifting space.

4 Living Spaces in Line Houses on a Former Tea Plantation Village

4.1 Outline of Village A, the Former Tea Plantation

Village A is located in the mountains at an altitude of about 1000 m on the way from Kandy, the capital of the Central Province, to the central highlands in the southeast. Village A was established as a tea plantation in 1883, and it is located near the Loolecondera Estate, the oldest tea plantation in Sri Lanka. It has a long history, but after Sri Lanka gained independence in 1948, the plantation was nationalized and sold to the private sector. Village A also went through a complicated process, and its business deteriorated, and it was closed down as a tea plantation in the early 1980s. Thereafter, plans were made to introduce forestry, spice cultivation, and other industries to replace tea production. However, these plans failed to take off and were abandoned.

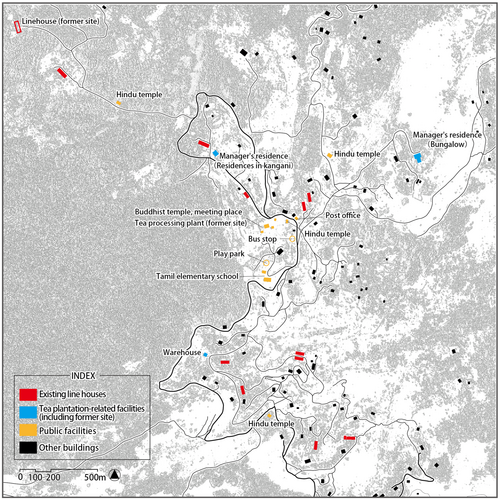

Today, there are almost no traces of the tea fields that once covered the entire village. Instead, the steep slopes of the village are covered with fields cultivated by the villagers, planted pine trees, and wastelands. In such a landscape, the line houses are distributed, and the Tamil people, the descendants of the former workers, live there (Figures 3 and 4). In addition to the line houses, there are also detached houses in the village. These houses were built recently, either by people from the village or by those who came to the village from outside. The details of the village population are not known, but according to the villagers, about 600–700 people live in an area of about 1.5 km2.

Village A is already closed as a tea plantation. Therefore, it is impossible to know the current problems of the tea plantation through this village. However, despite the fact that it is no longer operated as a tea plantation and has lost the incentive of employment in the tea industry, people are still staying in this village. Therefore, by focusing on Village A, it is possible to understand the relationship between the people and the line houses, not only as an object of management for tea production, but also as a subjective existence.

4.2 Survey and Current Status of Line Houses in Village A

In village A, 13 line houses still exist as of March 2020 (Figure 5). Based on villagers' information and aerial photographs of the village, it is estimated that there used to be about 15 to 20 line houses. However, some of the line houses have been lost as a result of vacancy and deterioration and there are now only ruins and the remains of foundations. Some of the existing line houses have been severely deteriorated or damaged and are being maintained by the residents. The land on which the line houses stand is owned by the government. The former workers and their descendants are allowed to continue to use the land as long as they live there. There are former facilities related to the tea industry such as a former processing factory, warehouse, manager's residence, and public facilities such as a school, bus stop, post office, temple, and assembly hall that support the daily lives of the villagers.

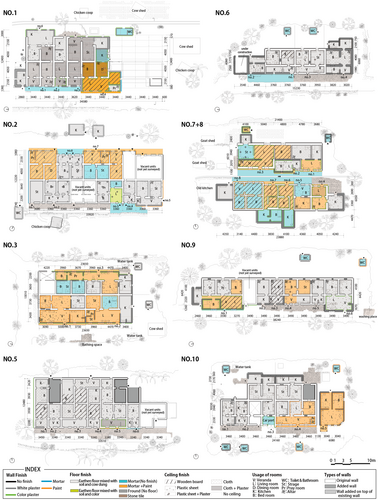

The survey of line houses was conducted from March 2014 to March 2020 during a total of 10 field visits. 10 buildings were able to be surveyed, and authors measured the buildings plans, observed, and recorded the current state of dwellings, use of each room, arrangement of furniture and household goods, traces of additions and alterations, surface finishes, surrounding environment, etc., and interviewed the residents about family structure and occupation, history of habitation, process of additions and alterations, daily care, etc.16 It spent a certain period of time to start the survey because it was necessary to establish a relationship with the villagers to be accepted by them.17 The line houses were constantly being modified by the residents, and changes occur in the spaces due to family member changes or building additions and renovations. The following analysis is basically based on information as of September 2018.

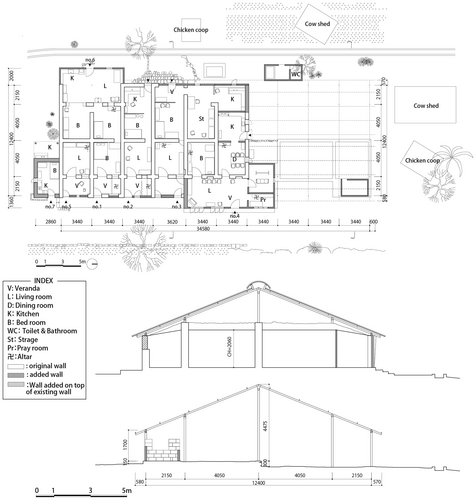

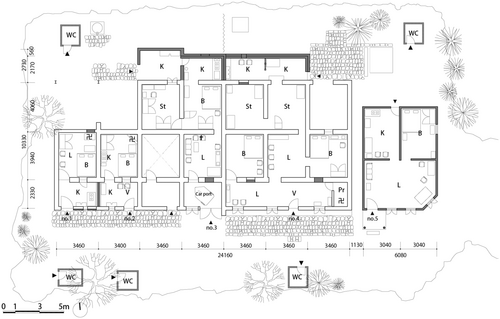

According to previous studies, there are three types of line houses: (1) double type (line house with dwelling units back-to-back along the ridge), (2) single type (verandah in front), and (3) single type (verandah in front and back) (Reference [1, pp. 20–21]). In village A, 6 line houses were identified as (1), another 6 as (2), and one as (3). According to the residents, all the line houses were built during the British colonial period.

Basically, the specifications of the line houses in village A have much in common with the standard specifications described in the manual (Table 2). On the other hand, the steel frame for roofing is not included in the manual. It is unclear at present whether this is a specification unique to the line houses in village A or not.

| Specification of line houses | Comment (comparison with the specifications in the manual) | |

|---|---|---|

| Site selection, building layout | Line houses are located in the former tea fields, centered around the manager's bungalow and factory. The space on the ridgeline and slopes is used to its full extent | Perhaps due to the strong spatial constraints of the site, there was no particular rule for the orientation of the building layout, and no particular measures were taken to deal with the southwest monsoon |

| There are four single-type buildings (no. 6, 7, 8, 9) and five double-type buildings (no. 1, 2, 3, 5, 10). Some of the buildings are arranged in a row (no. 7 and 8), but the rest are all arranged independently | The distance between the buildings is not being maintained. In addition, livestock sheds, toilets, and kitchens are now being built around the line houses | |

| Building shape, structure and materials | The height to the ridge of the roof is 14.7 ft. (double type) | It is kept below the height indicated in Manual 1, probably to prevent damage from strong winds |

| Each unit consists of a living room and a veranda. The size of the living room is 9.8–11.2 ft. × 10.2–12.5 ft. | The size of the room is close to the dimensions listed in the manual, 10 × 12 ft. (manual 1), 10–12 × 12 ft. (manual 2) | |

| The size of the veranda is 9.8–11.2 ft. × 5.6–6.6 ft. | The width of the veranda is close to the dimensions given in the manual, 6–7 ft. (manual 2). In many cases, the veranda is blocked off by a wall due to a lack of space | |

| The frames supporting the roof are made of iron (in some line houses, they are made of wood). The engravings on the frames suggest that they were made after 1857 | The steel frame is a specification that is not in the manual | |

| The roof is made of steel sheets | The roofing material matches the specifications for high and medium altitudes (Manual 1) | |

| The walls at either end of the line house are made of a local decorative stone called “black stone”. The stone is shaped into a rectangular block and stacked, and the walls are about 400 mm thick | The use of decorative stone on the walls at both ends is consistent with Manual 2. The thickness of the walls is almost the same as the value given in Manual 1 (15 in. = approx. 380 mm) | |

| Brick is used for the partition walls between the living spaces. The walls, pillars, and doors are finished with plaster both inside and outside, and the floors are earthen floors made from a mixture of cow dung and soil | The finishing materials are the same as in Manual 2. Walls and floors are often repainted. Recently, many buildings have been repainted with chemical paint or tiles | |

| Ventilation, drainage and facility | There is a vent on the ridge of the roof for smoke. Many households use firewood for cooking, and the smoke from the kitchen is exhausted through the attic and out of the vent | The installation of a ventilation opening (smoke vent) on the ridge of the roof is consistent with Manuals 1 and 2. Recently, propane gas has become more widespread, and some households have introduced gas stoves, but cooking with wood is still the norm |

| The area around the line house is paved with stones | The pavement around the row houses is as per the manual, however, there are some areas where the pavement is old and damaged | |

| The spring water from the surrounding mountains is brought in using the difference in elevation and is distributed to each line house. A waterway is drawn next to the line houses, and each household draws water from there, storing it in plastic tanks for drinking | There are times when it is difficult to secure water, and there is a shortage of water for daily use | |

| There are no private bathrooms or toilets, and small communal bath and toilet facilities have been built around the line houses | For hygiene reasons, it is built away from the line houses |

A total of 48 households and 210 people live in the 10 line houses as of September 2018. Counting multiple dwelling units integrated as one unit, the number of residents per unit is about 4.4, which is about equal to or slightly higher than the average for all plantations in the country (4.0 residents) [32]. The area per dwelling is about 455 ft2 (42.3 m2)18 and many of the dwelling units are above the average for the entire country's plantations and the standard set by the government (about 200 ft2). This is related to the fact that the area per dwelling unit is expanding due to repeated extensions and renovations.

About 63.3% of the residents living in line houses are of the working age population, aged 15–64, which is comparable to or slightly higher than the national average of 59.2% and the average of 57.0% for plantations as of 2016 [32].19 However, since there are no work opportunities within the village, many young people work outside the village. Therefore, on weekdays, especially during the daytime, young men are rarely seen in Village A, and children, elderly people, and women are more prominent.20 After the end of the civil war in May 2008, restrictions on the movement of Tamils decreased, and some went abroad to work.21 Tea plantations used to be a community isolated from the outside world. However, in recent years, residents have been moving in and out, increasing the mobility of the population.

4.3 Extension and Renovation of Line Houses

As people live in line houses and they are modified over the years, changes occur that were not included in the specifications in the manual. Examples of changes in line houses are shown in Figures 6 and 7. The roof of the line house is supported by a steel frame, and the base of the frame is reinforced by being embedded in a thick masonry wall (Figure 6). When the tea plantation was first established, one room and the veranda in front of the room were allocated to each family as their dwelling. Currently, the line houses are being extended by removing some of the existing walls between neighboring units, connecting multiple units by making a hole in the existing structure or removing walls, and some new buildings are nearby line houses (Figures 6-8). As a result, there is more room for living space per person. In addition, some renovations have been made to fill in openings such as verandas and windows and to build walls and shelves (Figures 9 and 10).

Each dwelling unit is occupied by children who have inherited it from their parents or relatives from generation to generation. In some cases, not only the buildings but also the furniture and household goods used since the grandparents' generation are carefully preserved. The above-mentioned renovation to fill and seal the openings may have functional reasons such as privacy and space saving. It also seems to be related to the idea that is unique to Tamil culture of keeping important things such as family members, household goods, and livestock out of sight as much as possible. Such a concept can be seen in the fact that altars for Hindu deities which are worshipped by many Tamils are located as far back from the entrance as possible.

Electricity was first installed in the village around 1990. Currently, each household pays for the installation of power lines to their homes. Some families still live with oil lamps in their dark rooms even in the daytime. Propane gas is used in some households, and they have cooking appliances, gas stoves, and stainless sinks in their kitchens. On the other hand, most households have cooking stoves and use firewood for cooking. This is not only due to economic constraints, as firewood is an easily accessible and inexpensive fuel, but also because of the lifestyle rooted in their religious beliefs. In other words, cooking and eating using a stove have meaning as a ritual before worshipping at a temple, and the kitchen is regarded as a sacred space.

Water is piped to the village from a water source in the nearby mountains, and each resident obtains water from a common water tap or well and carries it to their homes. Some households have plastic tanks in their yards to store water. The waterway is also used for washing dishes and vegetables.

Toilets are not segregated by sex as instructed in the manual and are shared in the vicinity of the tenement. If the residents are family members or relatives, they share a toilet; otherwise, each family has its own toilet. In addition, there are livestock sheds, a separate kitchen, and a warehouse in the vicinity of the tenement. Vegetable fields and livestock sheds are located further outside of the tenement.

4.4 Material Changes for Finish of Line House Buildings

Originally, natural materials such as soil, plaster, wood planks, and fabric were used to finish the walls, floors, and ceilings of line houses. Today, industrial products such as concrete blocks, mortar, color paint (chemical paint), and plastic are also used. Some residents also use a mixture of natural materials and industrial products. They uniquely arrange materials for finish, such as mixing plaster with color paint for floors and walls or plastering over plastic sheets for ceilings (Figure 11).

Table 3 shows the use of different materials for finishing the walls, floors, and ceilings. The largest number of exterior wall finishes is “no finish.” This is because the sides and back of the building, which are not easily seen from the street, tend to be left unfinished to keep low-cost. The front of the building is finished with white plaster or plaster mixed with colors. In recent years, highly durable paints have also been used. Interior walls are carefully finished. The use of paint is increasing, although the traditional material of plaster is still preferred. The most common floor finish is earthen flooring, with a mixture of soil and cow dung. There are many other types of floor finishes available, and they tend to be used according to financial resources and the purpose of the room. As described below, the use of earthen floors mixed with soil and cow dung seems to be preferred in kitchens. Wooden boards were not applied to the ceilings when the line houses were first constructed. However, because of the problems of dust and cooking smoke, simple materials such as sheets and cloth are used for the ceilings. When funds are available, ceilings are affixed with wooden boards.

| No. 1 | No. 2 | No. 3 | No. 5 | No. 6 | No. 7 | No. 8 | No. 9 | No. 10 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wall finish (exterior wall) | ||||||||||

| No finish | 12.2% | 5.6% | 27.9% | 32.3% | 72.3% | 35.3% | 48.0% | 65.2% | 54.9% | 39.3% |

| White plaster | 37.1% | 53.6% | 19.8% | 46.4% | 27.7% | 27.3% | 29.1% | 15.7% | 9.2% | 29.6% |

| Color plaster | 45.2% | 0.0% | 52.3% | 21.4% | 0.0% | 37.4% | 13.1% | 13.4% | 1.5% | 20.5% |

| Mortar | 5.4% | 11.9% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 1.9% |

| Paint | 0.0% | 28.9% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 9.7% | 5.7% | 34.4% | 8.7% |

| Wall finish (interior wall) | ||||||||||

| No finish | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 13.4% | 15.3% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 1.1% | 3.3% |

| White plaster | 77.4% | 67.1% | 40.3% | 81.6% | 84.7% | 46.3% | 24.5% | 76.3% | 61.8% | 62.2% |

| Color plaster | 22.6% | 3.5% | 14.2% | 5.0% | 0.0% | 53.7% | 53.1% | 23.7% | 2.5% | 19.8% |

| Paint | 0.0% | 29.4% | 45.5% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 22.4% | 0.0% | 34.6% | 14.7% |

| Floor finish | ||||||||||

| Earthen floor mixed with soil and cow dung | 66.8% | 47.4% | 22.8% | 67.0% | 70.7% | 27.0% | 11.9% | 56.1% | 45.9% | 46.2% |

| Earthen floor mixed with soil and color | 0.0% | 2.9% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.3% |

| Mortar (No finish) | 11.4% | 14.7% | 13.5% | 0.3% | 14.7% | 21.9% | 45.9% | 3.4% | 5.7% | 14.6% |

| Mortar + paint | 19.6% | 27.8% | 59.4% | 0.4% | 0.0% | 38.6% | 34.0% | 28.8% | 27.2% | 26.2% |

| Ground (No floor) | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 14.3% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 3.9% | 2.0% |

| Stone tile | 2.2% | 7.2% | 4.3% | 18.0% | 14.6% | 12.5% | 8.2% | 11.6% | 17.3% | 10.7% |

| Ceiling finish | ||||||||||

| Wooden board | 12.2% | 33.4% | 0.0% | 19.7% | 5.5% | 39.1% | 46.9% | 17.8% | 0.0% | 19.4% |

| Plastic sheet | 7.7% | 31.8% | 42.7% | 29.0% | 37.4% | 10.5% | 26.6% | 35.0% | 64.4% | 31.7% |

| Plastic sheet + plaster | 0.0% | 28.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 10.7% | 11.8% | 0.0% | 10.8% | 0.0% | 6.8% |

| Cloth | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 18.3% | 18.8% | 24.8% | 0.0% | 17.8% | 0.0% | 8.9% |

| Cloth + Plaster | 59.9% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 4.7% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 4.8% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 7.7% |

| No ceiling | 20.1% | 6.8% | 57.3% | 28.3% | 27.6% | 13.8% | 21.7% | 18.6% | 35.6% | 25.5% |

- Note: The dark gray hatches indicate the most common type of finish for each line house. The light gray hatches indicate the second most common type of finish.

Figure 12 shows the use of the finishing materials as well as the function of the rooms in line houses and modifications of rooms.

Line house No. 2 was originally a line house with two rows of 20 units, but now there are several units connected together for a total of 11 units. The exterior walls of the units on the south side (No. 1, the south side of No. 2 and No. 3–5) and some units on the north side (No. 7 and No. 11) are finished with plaster, and the appearance of the building remains close to its original form. Many of the rooms also use natural materials, such as earthen floors mixed with cow dung and walls finished with plaster. The ceilings are simply covered with plastic sheets, but some units (No. 2, No. 4, and No. 7) are plastered over the plastic sheets. As on the south side of No. 2, the use of traditional finishing materials is evident throughout the buildings in line house No. 5 and No. 6, and partially in No. 1, No. 9, and No. 10. The units on the north side of line house No. 2 have been extended or renovated. The location of the original wall has been changed and the rooms expanded (No. 2 north, No. 8, and No. 9). Finishes of walls, floor, and ceiling have also been changed to paint, mortar, and wooden boards. However, natural materials such as soil and cow dung for earthen floors and plaster are still used in some rooms behind (B, St in No. 8) and the kitchen. Especially in the kitchen, it seems to be preferred that floors are finished with earthen floors mixed with soil and cow dung, and the stove and walls are plastered.

Line house No. 3 has been further consolidated into multiple dwelling units, and the original two rows of 12 units are now only three units. Almost all of the original masonry exterior walls have been replaced with concrete block walls and painted with a mixture of plaster. Mortar, paint, and plastic sheeting are also used for interior finishes. The kitchens are finished with earthen floors and plastered walls (dwelling No. 2 and No. 3) and each kitchen has a door leading to the garden. Unit No. 2 was renovated to accommodate the son who has gotten married recently. The marriage ceremony was also held at this house after visiting the wife's parents' house. In unit No. 3, only the unit where the living room (L) is now located was originally used by the family. They were purchased one by one whenever a vacant room became available. Previously, each of the seven children had been given a dwelling unit. After the children became independent, with the exception of the oldest daughter and the youngest son, the 5 units were connected and used as one large dwelling. They received financial support for the renovation from their daughter who went abroad to work. As in No. 3, new finishing materials were used extensively in line house No. 7 + 8, and there are traces of repeated additions and renovations of walls and buildings.

Line house No. 9 was originally a row of 11 units, but now has 7 units due to the connection of multiple dwelling units. In this line house, the use of new and old finishing materials is more complicated. In unit No. 5, the exterior finish is plastered and remains close to that of the original construction, but the interior flooring has been changed to mortar and paint except for the kitchen. The kitchen remains with its earthen floor and plastered finish. In units No. 3 and No. 4, the opening of the veranda in front of the unit has been blocked with concrete blocks. The blocks are finished with plaster and appear to blend well with the original exterior walls. The units at both ends (No. 1 and No. 7) are under renovations for changing the position of the exterior wall in front of the building. Another feature of renovation in this line house is that the windows in the rear rooms are partially or completely blocked up; unlike double-type line houses, the rear rooms of single-type line houses face the outside. Although this is a disadvantage in terms of ventilation and lighting, almost all the openings are blocked. It is perhaps due to the influence of the Tamil culture of keeping important things away from the public eye, as mentioned above.

4.5 Material Circulation Through Maintenance of Line Houses

Among the line house finishes, those made of natural materials are frequently maintained. According to the residents, the plastered walls are repainted every 6 months and the earthen floors mixed with soil and cow dung are repainted every 1 or 2 weeks. The reason for the high frequency of repainting is not only that the material is vulnerable and difficult to maintain without frequent maintenance, but also that cows are sacred to the Hindu community. Particularly in connection with the latter reason, repainting the earthen floors with cow dung has become a ritualized activity and therefore it is persistent.

Temples, shrines, and other religious-related facilities were the few places on the tea plantations that were under the control of the workers rather than the plantation owners. In Tamil culture, the power of the gods is believed to reside in the earth itself (Reference [27, p. 204]). Worship and festivals were healing for the workers. Their practice of maintaining shrines and temples to the gods of the plantation lands has been documented by many researchers [3, 6, 34].

In Village A, many residents worship at the village temple or shrine on Tuesdays and Fridays (the gods worshipped differ on the day of the week in Hinduism). Prior to worship, they purify their bodies by bathing. They also often repaint the earthen floors and walls with a mixture of cow dung or plaster. They mix cow dung, soil, and water in a bucket, knead, and apply it to the earthen floor with their bare hands or a cloth.

In addition, as seen in the previous section, when there is a stove, the finish of the kitchen space tends to remain the earthen floor or plastered walls (Figures 13 and 14). The reason for this may be that maintenance costs get higher if industrial products are used for finish, since cooking is done in the stove using firewood, and they tend to attract dirt from smoke and soot. Another reason is that the kitchen spaces are sacred places in Hinduism, and keeping them clean by periodic repainting is important to the people in their faith.

In the past, earthen floors mixed with soil and cow dung were reported as causes of poor living conditions in line houses.22 However, to the villagers, cows are both domestic animals and sacred existences. Cattle manure is used as fertilizer in the fields, and cow milk and vegetables from the fields provide a source of nutrition and shape the bodies of the inhabitants. The line house dwellers also use cow dung and other materials to maintain the space of their dwelling, an act that maintains the space for their survival. At the same time, this act has many ritualistic connotations and is an important component of their faith-based lifestyle.

In and around line houses, there are signs to indicate some kind of boundary. They are dried and tied straw or other plants, animal bones, etc. and posted at the entrances to houses, vegetable fields, livestock sheds, kitchens, washing areas, and so on (Figure 15). Hindu deities are said to dwell not only on the land, but also in people and houses. The relationship between man, house, land, family, and kin was inextricably linked. Thus, the gods also dwell in all of those chains (Reference [27, pp. 205–206]). These signs suggest that in the mutually defining relationship of man, land, and god, the materials that shape the inhabitant's body circulate, extending the inhabitant's body into the surrounding environment.

5 Conclusion: The Ambiguity of the Line Houses in the Context of the Former Tea Plantation

This paper reviews the history of tea plantations in Sri Lanka, especially the transformation of the living environment for plantation workers and the establishment of tenements, locally called line houses. In addition, a comparison was made between the prototype of the line house, a standard design described in a manual for planters, the discourse of the managers and residents related to the line house, and the current situation of line houses in the former tea plantations, Village A, to explore the image of the Tamil people's living space on the tea plantations. Based on the results of this analysis, it is emphasized that it is problematic that the current living environment of the line houses can be lumped together under the government's term “inadequate” and “poor” environment.

It is clear that when tea plantation line houses were first constructed, considerable attention was paid to maintaining a hygienic environment in their specifications and management. This was, of course, due to the nature of the plantation as a production facility. The rationale was that maintaining the health of the workers was directly related to maintaining and improving the efficiency of tea production. Although the government's current plan emphasizes the “poor” living environment of the line houses, it is difficult to believe that the plantation lacked consideration for the living environment from the beginning of its construction due to its nature as a production facility. If there is a problem, it is the deterioration of functions due to the aging of the buildings and facilities. In addition, there is a mismatch between the minimum architectural standards of the old time and those required for modern life. The mismatch is caused by the purpose of managing the residents as laborers, the division of relationships among the residents, and social aspects such as stereotypes about line houses and tea plantations.

In the line houses of the former tea plantation Village A, people repeatedly extend and renovate their line house buildings to accommodate changes in their family structures and lifestyles, and maintain them through their daily lives and beliefs. Through such activities in the line houses, materials circulate between the people and the environment. The activities of the people and the movement of materials presented in this study are proof of the existence of life and human space in the line houses. They are in sharp contrast to the image of nonlife and nonhuman space of the tea plantation line houses in the traditional discourse, mainly by government agencies and aid workers. At the same time, it also made us strongly aware of the existence of “uru” which is considered an important part of Tamil culture. The materials that make up the line house buildings and the surrounding nature, such as livestock, crops, and soil circulate through the daily activities of the people in the line houses. Through daily life and rituals, the inhabitants of the tenement also become part of the circulation, and their bodies and beliefs are constituted. This identification of people and place was an important element that characterized their uru. This is the image of a plantation line houses maintained and managed by the inhabitants which is very different from the “poor living environment” emphasized in the government's social development plan.

What does it mean that the residents of the line houses in village A continue to live there even after the tea plantation has closed? This is a question that is also related to the essence of “uru,” which is to form the agency and personality of people who share the same soil. In the case of Village A, the characteristics of the line houses do not necessarily fit to the existing discourse that affirms the existence of life and human space in the line houses with expressions, such as “contradiction and conflict,” “instability and heterogeneity,” or “material evidence of resistance to stereotypes about tea plantations.” This is probably due to the fact that more than 30 years have passed since the closure of the tea plantation, and the connection of space and society for tea production, with the plantation owner at the top, is absent in Village A. Village A looks like an ordinary rural area that can be found anywhere in Sri Lanka, and the traces are disappearing that remind us that this village used to be a tea plantation.

However, this is precisely why the heterogeneity of the nearly 150-year-old line houses that still remain in the village stands out. This is partly because of the tenement-style appearance of the building, which is not appropriate for a village deep in the mountains, but also because of the ambivalence of the tenement, which is brought about by the relationship between the line houses and its inhabitants. The line houses are maintained and embodied by the inhabitants, who are the descendants of laborers and inheritors of Tamil culture. For them, the line houses are a place to return to, and therefore an object of investment and attachment. On the other hand, as can be seen from the fact that many people leave the village to find work, the inhabitants are not always willing to stay rooted in the line houses. This may have something to do with the memories of suffering as a tea plantation worker and the stigma that comes with being from a plantation.

The ambivalence of the line houses, the property of being a place to return to and not necessarily to take root, represents a general character of place. However, the line houses take on a special significance when they are tried to understand their placeness within the complex historical context of Sri Lankan tea plantations. The fact that they lived on plantations while experiencing hardships and at the same time reproduced and developed customs based on Tamil culture gives the tenement house a unique character. When viewed in this way, the existence of the line house may bring conflict or complex feelings to the residents, but it is by no means contradictory. For them, the line house is a proof of their existence from the past to the present, and it has a meaning more than an address or land ownership.

The recent proposals for social development, such as the replacement of the tenements with new houses and the granting of ownership, may erase the evidence of their existence and should be carefully considered. According to the government policy, resettlement is planned for the convenience of plantation management and administration. However, for the Tamils in tea plantations who have finally gained freedom of movement, the housing provided by the government may prevent them from living in a place where they feel safe and where they can be actively involved, such as in the line houses discussed in this paper. If so, the government's intention to keep them on the plantation as “laborers” would be difficult to realize.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Professor Samitha Manawadu (now Professor Emeritus) of the Faculty of Architecture, University of Moratuwa and the staff of the Ceylon Tea Museum Library for their cooperation in my data collection and the residents of Village A for their cooperation in my field survey.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Endnotes

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

Research data are not shared.