Experimental Research on the Guidance Effect of Residents' Rooms and Restroom Signs for the Elderly With Dementia: Research on the Systematic Construction of an Environment With Non-Pharmacological Therapy Using Signs Part 2

Funding: The authors received no specific funding for this work.

The Japanese version of this paper was published in Volume 87 Number 791, pages 1–11, https://doi.org/10.3130/aija.87.1 of Journal of Architecture and Planning (Transactions of AIJ). The authors have obtained permission for secondary publication of the English version in another journal from the Editor of Journal of Architecture and Planning (Transactions of AIJ). This paper is based on the translation of the Japanese version with some slight modifications.

ABSTRACT

This study focused on the guiding effect of residents' room signs and restroom signs displayed in group homes for elderly individuals with dementia. The results indicated that wandering behavior was primarily observed in residents with moderate dementia. An analysis of their behavior showed that while they had a general sense of the location and direction of their intended destination and could correctly reach the area around it, they were unable to identify the precise location in the final process of selecting the correct door. In contrast, when text-based signs displaying residents' names or “restroom” were used, these served as cues to help identify the precise location, thereby preventing wandering behavior.

1 Introduction

1.1 Background and Purpose

In recent years, Japan's population has been aging, with the elderly population accounting for 29.1% of the total population in October 2023 [1]. The number of elderly with dementia is also expected to increase significantly, from 4.62 million in 2012 to up to 8.3 million in 2030 [2]. One of the symptoms of dementia is disorientation,1 which causes blurred perceptions about location and contributes to the development of various BPSD,2 such as wandering and incontinence. In contrast, appropriate care environments that assist in independent living for persons with dementia are considered effective as non-pharmacological therapy. As part of this effort, group homes for the elderly with dementia (GH) are installing signs (residents' room signs and restroom signs) around the doors so that residents' room and restroom locations can be identified by elderly with dementia. In the previous report [3], with the aim of creating a care environment using residents' room signs as a medium, we clarified the needs of the staff engaged in care in GH for residents' room signs and the planning conditions related to the planning of residents' room signs targeting audiences with dementia. On the contrary, in Japan, the effect of assisting the elderly with dementia to identify their destination using signs as cues and to reach it independently (guiding effect) has so far been limited to awareness surveys such as questionnaires targeting staff, and no studies have directly verified the effect on the elderly with dementia.

Therefore, this study aims to clarify the guiding effect of residents' room signs and restroom signs, which are frequently used by elderly with dementia, among the signs displayed in GHs, through an experimental study on target audiences with dementia.

1.2 Review of Previous Research

As a study that verified the guiding effect of installing some kind of information for identification around the door, Namazi [4] conducted a controlled experiment in which a display cabinet in front of the resident's room was placed with items that were linked to the residents' memories before the progression of dementia and items that were not linked to their memories. The results of the study reported that placing items linked to residents' memories before the progression of dementia led to the identification of their rooms, and that items dating back to childhood in particular were more effective. On the contrary, items that were not linked to memory, while of interest, did not provide clues to identifying the resident's room. The most effect was observed for those with moderate dementia, while those with mild dementia were able to identify their resident's room in both situations, and conversely, those with severe dementia were not able to identify their resident's room in either situation. Hanley [5] tested whether combining training with an environment in which signs such as three-dimensional, large pictures and objects were placed would improve disorientation in elderly with dementia. The results report that the combination of disorientation training and signs was effective, whereas the installation of signs alone was less effective. Amemiy [6] examines the effects of differences in door design and usage patterns on the door responses of elderly with dementia. The results reported that although the color change of the door did not change the response, keeping the door open led to behaviors such as peeking inside and entering.

On the contrary, as a study dealing with the guiding effect of residents' room signs and restroom signs actually used in GHs in Japan on elderly with dementia, Tanaka [7-10] summarizes the understanding of the status of signage display and staff evaluation of guiding effect based on a questionnaire survey targeting elderly welfare facilities throughout Japan. As a result, resident's room signs tended to be displayed in many GHs with “resident's name” and “residents' personal mementos” displayed, and staff evaluation of the guiding effect was also high. Furthermore, many GHs displayed both “text” and a “pictogram” for restroom signs, and there was a tendency for staff evaluation to be particularly high for text signage. The accumulation of these staff surveys suggests that specific residents' room signs and restroom signs have a certain guiding effect. However, at present, there are no studies that have directly verified the guiding effect on elderly with dementia as a target audience.

2 Research Methods

2.1 Subject of an Investigation

The survey facilities were conducted at three GHs in Tokyo, which were randomly selected from 45 GHs that had obtained permission for ongoing fieldwork during the questionnaire survey3 conducted in the previous report [3], and which were also permitted to conduct the present survey (Table 1). Although each GH is composed of several units, one unit per GH was targeted from among them. In selecting the units, we held discussions with the staff to select units with the least bias towards residents with dementia, while taking into consideration the residents' conditions. Note that each unit will not be used by residents of a different unit than the one being surveyed.

| Facility name | Address | Number of units | Capacity of units studied | Number of staff for units studied | Survey start date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum number of beds | Number of residents | |||||

| YU | Nakano-ku, Tokyo | 2 | 9 | 8 | 6 | Jul. 27, 2016 |

| WA | Ota-ku, Tokyo | 3 | 9 | 9 | 7 | Aug. 22, 2016 |

| KA | Arakawa-ku, Tokyo | 3 | 6 | 6 | 10 | Sep. 24, 2016 |

2.2 Method of Investigation

2.2.1 Preliminary Explanation and Coordination

Prior to conducting this study, materials were distributed, and oral explanations were given to facility directors and staff regarding the outline of this study. Subsequently, based on the condition of the residents and discussions with the staff, the schedule and survey method were adjusted, and as far as possible, the content of the survey was determined to be consistent among the three facilities. In addition, relatives of residents were informed through the facility according to their individual circumstances.

2.2.2 Survey of Resident Demographics

Prior to the verification experiment, a survey was conducted to determine the demographics of the residents belonging to each GHs (Table 2). The survey method consisted of a survey form in which residents were asked to select the items that applied to their individual conditions, and staff members who were familiar with the residents' conditions responded to the form. The survey questions were created by citing items from the primary survey used to determine the level of care for elderly individuals with dementia,4 specifically those items that are considered relevant to the interpretation of signs. Based on the level of care and cognitive disorders of the residents obtained, the progression of dementia was then classified as “mild,” “moderate,” or “severe”.

| Progression of dementia | Residents name | Residents' attributes | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level of care | Daily life independence level | Corrected eyesight | Walking status | Toilet assistance | Cognitive disorders | |||||||

| Understanding own name | Understanding daily routine | Communication of intent | Short-term memory | Orientation disorder | ||||||||

| Time | Location | |||||||||||

| Mild | YU-A | 2 | IIb | None | Independent | Some assistance | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| YU-B | 2 | IIb | None | Independent | Independent | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | |

| YU-C | 2 | IIb | None | Independent | Independent | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| YU-D | 2 | IIb | None | Independent | Independent | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| YU-E | 1 | IIb | None | Independent | Independent | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| YU-G | 1 | IIb | None | If holding support | Independent | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| WA-F | 1 | IIa | About 1 m | If holding support | Supervised | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| WA-H | 2 | IIa | About 1 m | Independent | Independent | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| KA-A | 1 | I | None | Independent | Independent | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | |

| KA-F | 2 | IIa | None | Independent | Some assistance | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | |

| Moderate | YU-H | 2 | IIb | None | Independent | Some assistance | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| WA-A | 2 | IIb | About 1 m | If holding support | Supervised | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | |

| WA-B | 3 | IIb | About 1 m | If holding support | Some assistance | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | |

| WA-C | 2 | IIb | About 1 m | If holding support | Some assistance | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | |

| WA-E | 2 | IIa | About 1 m | If holding support | Supervised | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | |

| WA-G | 2 | IIIa | About 1 m | Independent | Supervised | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | |

| KA-C | 3 | IIIa | None | If holding support | Some assistance | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | |

| Severe | YU-F | 4 | IV | None | Independent | Fully assisted | No | No | Sometimes | No | No | No |

| WA-D | 2 | IIIa | None | Independent | Supervised | No | No | Sometimes | No | No | No | |

| WA-I | 4 | IV | About 1 m | Independent | Fully assisted | No | No | Sometimes | No | No | No | |

| KA-B | 3 | IIIa | None | Fully assisted | Some assistance | Yes | No | Sometimes | No | No | No | |

| KA-D | 5 | IV | Undetermined | Fully assisted | Fully assisted | No | No | No | No | No | No | |

| KA-E | 4 | IIIa | None | Fully assisted | Some assistance | No | No | No | No | No | No | |

2.2.3 Verification of Effectiveness of Resident's Room Signs and Restroom Signs

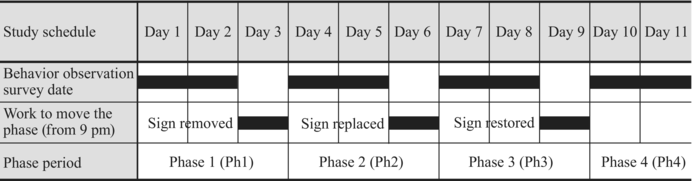

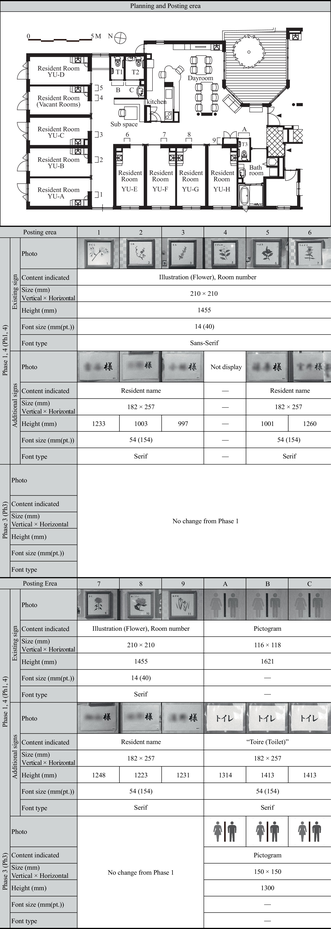

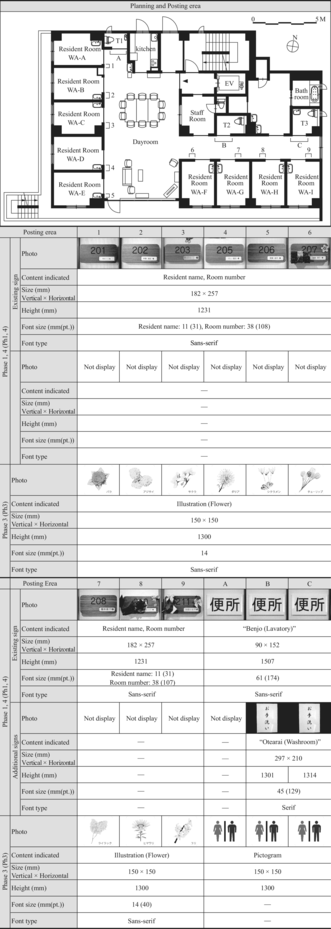

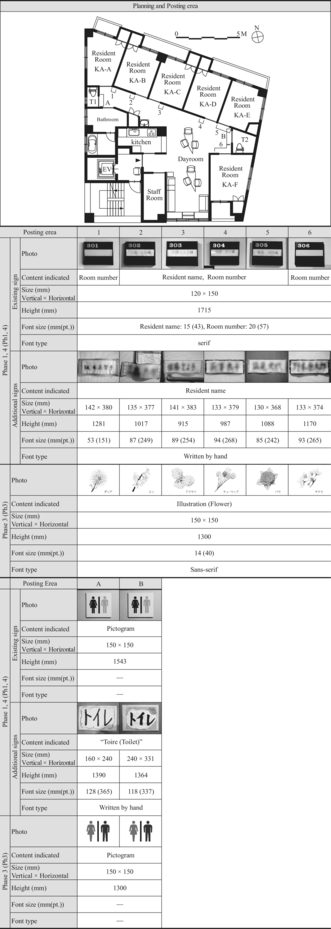

To verify the guiding effect of the residents' room signs and restroom signs, we conducted a behavioral observation survey of the residents by changing the content of these signs displayed on the walls over four phases (Tables 3–6). Additionally, the height at which the signs were displayed and the font size of the text were measured according to the standards outlined in Table 7.

|

|

|

|

| Item | Measurement standard |

|---|---|

| Height of display | Height from floor to center of sign |

| Text size |

|

| Residents name | Residents observed wandering behavior due to moving resident room | Residents observed wandering behavior due to moving restroom | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WA-B | WA-D | WA-A | WA-G | KA-C | |

| Phase 1 (Ph1) | |||||

| Number of times induced by a third party | 3 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Number of times reaching destination alone | 7 | 11 | 3 | 5 | 2 |

| Number of occurrences of wandering behavior | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Rate of wandering behavior for moving alone | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Phase 2 (Ph2) | |||||

| Number of times induced by a third party | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| Number of times reaching destination alone | 9 | 6 | 2 | 8 | 2 |

| Number of occurrences of wandering behavior | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 |

| Rate of wandering behavior for moving alone | 18% | 0% | 50% | 0% | 33% |

| Phase 3 (Ph3) | |||||

| Number of times induced by a third party | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| Number of times reaching destination alone | 7 | 8 | 2 | 5 | 0 |

| Number of occurrences of wandering behavior | 2 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Rate of wandering behavior for moving alone | 22% | 0% | 50% | 17% | 100% |

| Phase 4 (Ph4) | |||||

| Number of times induced by a third party | 4 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 3 |

| Number of times reaching destination alone | 5 | 7 | 3 | 11 | 3 |

| Number of occurrences of wandering behavior | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Rate of wandering behavior for moving alone | 0% | 22% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

|

Phase 1 (Ph1) is an environment where residents' room signs and restroom signs are already displayed and in operation prior to the study intervention. These signs are classified into two categories: those planned and installed by the architect at the time of building completion (existing signs) and those displayed by staff as an adjunct (additional signs). In particular, additional signs were added by staff because the existing signs did not meet the requirements for use by elderly with dementia. In Ph1, all units were pre-equipped with text-based signs such as “resident's name” and “restroom”, using either existing signs or additional signs. Therefore, the effect of text-based information was evaluated using these signs.

In Phase 2 (Ph2), all residents' room signs and restroom signs were removed, and the search for locations in an environment with no signs cues was verified. For signs that were difficult to remove, measures were taken to cover the relevant information, rendering them unreadable. Furthermore, signs5 and wall decorations6 other than residents' room signs and restroom signs were also removed, or the information they contained was covered, as they could potentially serve as clues for location search.

In Phase 3 (Ph3), starting from an environment where all signs from Ph2 had been removed, illustrations and pictograms were added to evaluate whether they could serve as substitutes for text-based information. Residents' room signs displayed different floral illustrations as information not directly associated with the residents. In addition, the pictogram “Japanese Industrial Standards Z8210 Toilets”, which is commonly used in public facilities, was displayed for restroom signs. Each sign was made 150 mm long by 150 mm wide and displayed at a height of 1300 mm.

In Phase 4 (Ph4), the environment was restored to be similar to Ph1, and the effect of displaying text-based signs was re-evaluated.

The removal, replacement, and restoration of signs for the Ph transition took place after 9:00 p.m., when residents went to bed. This was set up so that the sign would be in a changed state upon waking for the resident.

2.2.4 Summary of Behavioral Observation

During discussions with the staff, a request was made to minimize the number of investigators assigned to the behavior observation survey in consideration of its potential impact on the residents. Therefore, a preliminary survey was conducted in Facility YU, which is the most difficult for the investigators' line of sight to pass through due to the facility's floor plan, and it was confirmed that a survey could be conducted by two people.

Behavioral observation surveys were conducted for a total of 8 days, 2 days for each phase. The survey was conducted from 9:00 a.m. to 6:30 p.m. As a rule, two investigators were assigned to the survey to record the resident's line of movement, the nature of his/her behavior, whether the signs were visible or not, and the method of staff intervention. However, only in cases where there were significantly fewer residents, the survey was conducted with only one investigator. Additionally, Facility YU was unable to obtain permission to remove or change the residents' room signs due to consideration of the residents' symptoms. Therefore, we conducted a behavioral observation survey at Facility YU by changing the content of displays only for restroom signs. For the same reason, the behavioral observation survey for Ph4 was also conducted for only 1 day.

3 Results

3.1 Overall Trend of Wandering Behavior

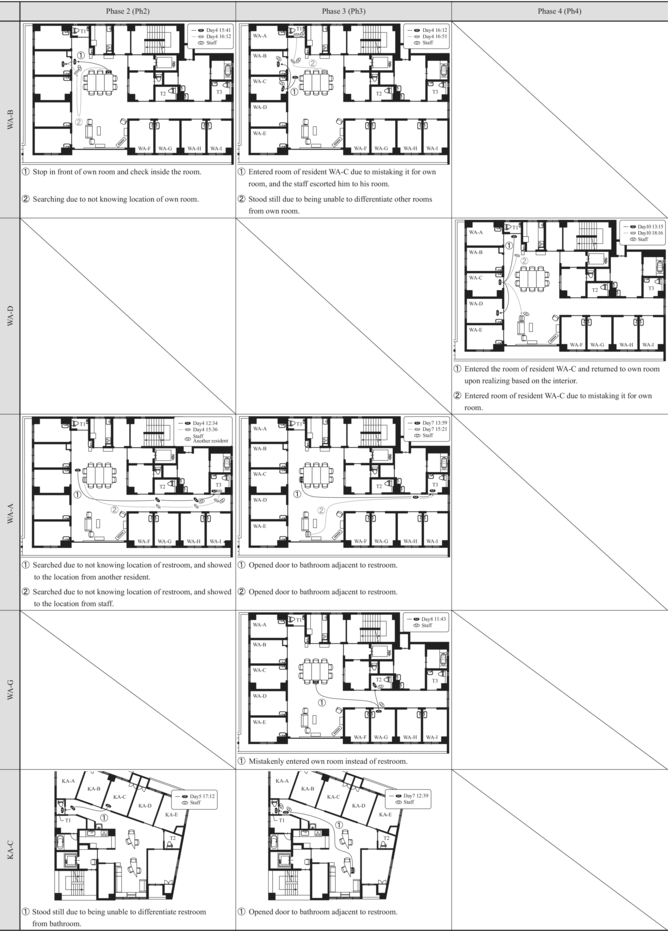

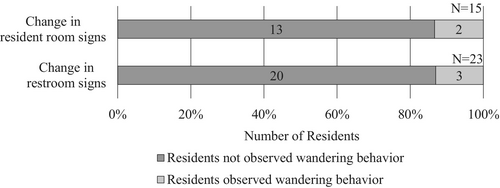

During the behavioral observation survey, wandering behavior was observed when residents were going to their resident's room or restroom, such as not recognizing the location and looking for it, or accidentally entering other areas. The overall trend throughout each phase showed that residents who exhibited wandering behavior when heading to their rooms were found in two residents (13%), residents WA-B and WA-D, out of a total of 15 residents, excluding Facility YU for whom permission to remove or change their residents' room signs was not received (Figure 1). The wandering behavior when going to the restroom was observed in three residents (13%), residents WA-A, WA-G, and KA-C, out of a total of 23 residents.

Characteristically, all of the residents who exhibited wandering behavior did so only when moving to either the resident's room or the restroom, and none of the residents exhibited straying behavior when moving to both the resident's room and the restroom. Furthermore, when we looked at the frequency of each resident's wandering behavior, we found that in many cases wandering behavior did not always occur, although it varied from 18% to 100% depending on the resident and the phase (Table 8).

3.2 Relationship Between Dementia Symptoms and Wandering Behavior

A comparison of resident demographics and the occurrence of wandering behavior showed differences according to the degree of progression of dementia. The 10 residents with mild symptoms and no cognitive disorder were observed to reach their destination without wandering behavior in Ph2 and Ph3, even after changes were made to residents' room signs and restroom signs. Thus, if the ability to grasp the location is not impaired, it is possible to locate the desired location regardless of the presence or absence of residents' room signs and restroom signs, as is the case with normal persons.

Of the six residents with severe cognitive disorders, residents KA-B, KA-D, and KA-E, who had difficulty walking, were transferred to wheelchairs and guided by staff. As a result, residents did not have the opportunity to explore their resident's rooms and restrooms independently. Residents YU-F and WA-I, who were able to walk independently, were frequently seen wandering around the unit, but were unable to recognize residents' room signs or restroom signs and needed to be guided by staff. In other words, we believe that many residents with severe disabilities are not in a position to live independently, and therefore, the guiding effect of residents' room signs, restroom signs, and the like was not observed. Resident WA-D, who is also severely impaired, is becoming increasingly unable to communicate due to cognitive decline but is still capable of independently moving to their resident's room or the restroom. However, the behavioral observation survey revealed that WA-D did not appear to use the signs.

On the other hand, the residents most affected by changes in residents' room signs and restroom signs were those with moderate cognitive disorders who were still capable of relatively independent living. Among the seven residents, WA-B, WA-A, WA-G, and KA-C exhibited wandering behavior in Ph2 or Ph3, where changes were made to the residents' room signs and restroom signs. Common characteristics among these residents included being able to walk independently (marked as “Independent” or “If holding support” in Table 2) and having coexisting short-term memory impairment and disorientation.

Based on the above findings, residents' room signs and restroom signs serve as crucial cues for location finding, particularly for the elderly with moderate cognitive disorders, and are believed to contribute to the reduction of wandering behavior. These results are consistent with the previous research by Namazi [4].

3.3 Behavioral Details of Residents Exhibiting Wandering Behavior

This section summarizes the specific behaviors of five residents who exhibited wandering behavior during the behavioral observation study (Tables 8 and 9).

3.3.1 Residents Who Exhibited Wandering Behavior While Moving to Their Resident's Rooms

3.3.1.1 Case of Resident WA-B

In the behavioral observation study, the number of times resident WA-B moved towards their resident's room was confirmed to be 41 times across all phases. Of these, there were 9 instances (22%) where they were guided by a third party, such as staff or another resident, and 32 instances (78%) where they moved independently.

The wandering behavior of resident WA-B occurred only during Ph2 and Ph3. In Ph2, at 15:41 on Day 4, resident WA-B was observed to be unable to recognize the location of their room while returning from the day room, resulting in behaviors such as stopping around their room area to search for their room and peering into their room for confirmation. Furthermore, at 16:12 on Day 4, they were observed wandering while searching for their room. In Ph3, at 16:12 on Day 8, resident WA-B accidentally entered the room of resident WA-C, and staff noticed this and guided them back to their own room. Furthermore, at 16:51 on Day 8, the resident paused near their room, looked around, and peered inside, indicating an attempt to find their room. However, no wandering behavior was observed in Ph1 and Ph4, and on Day 10, the resident was observed standing in front of the resident's room sign, gazing intently at the name from close proximity before entering their room. Based on this, it is considered that resident WA-B recognizes their room using the resident's room sign as a cue.

3.3.1.2 Case of Resident WA-D

Resident WA-D was observed heading towards their room a total of 36 times across all phases. Of these, there were two instances (6%) where they were guided by a third party, and 34 instances (94%) where they moved independently.

Resident WA-D did not exhibit wandering behavior in Ph2 and Ph3, where the signs were changed, but it was observed in Ph4, where the signs were restored. At 13:15 on Day 10, resident WA-C mistakenly entered another resident's room, noticed the interior, realized the mistake, and then returned to their own room. Furthermore, at 18:16 on Day10, resident WA-D was observed entering resident WA-C's room again and being called back to the day room by staff. Resident WA-D did not exhibit wandering behavior in Ph1 through Ph3, and throughout all phases, they were observed checking the interior of the rooms. This suggests that they do not rely on the resident's room sign on a daily basis but instead use the interior as a cue to identify their own room. On the other hand, the occurrence of wandering behavior only in Ph4 suggests that the significant environmental changes due to the restoration of many signs and decorations may have been a contributing factor.

3.3.2 Residents Who Exhibited Wandering Behavior While Moving to Their Restroom

3.3.2.1 Case of Resident WA-A

Resident WA-A was observed moving to the restroom a total of 19 times across all phases. Of these, there were five instances (26%) where they were guided by a third party, and 14 instances (74%) where they moved independently. Among the three restrooms in the unit, restroom T1 was used six times and T3 was used eight times during independent movements. When moving from their own room to the restroom, T1, which is the closest, was typically used. Conversely, when they were in the day room, T3 was used.

Resident WA-A exhibited wandering behavior in Ph2 and Ph3, with an occurrence rate of 50%, which was higher compared to other residents. In Ph2, on Day 4 at 12:34 and 15:36, Resident WA-A was observed wandering the hallway looking for restroom T3 and had to be guided by staff or other residents to find its location. In Ph3, on Day 7 at 13:59 and 15:21, Resident WA-A was observed mistakenly opening the door to the bathroom adjacent to the restroom, then realizing the mistake upon seeing the interior and proceeding to the restroom. These wandering behaviors were characterized by an initial ability to move in the correct direction. However, due to a lack of precise location awareness when choosing the final door, the resident ended up walking around the hallway or mistakenly opening the bathroom door. On the other hand, no wandering behavior was observed in Ph1 and Ph4, and on Day 10 at 16:00, the resident was seen moving to the door of restroom T3, visually confirming the text on the sign from close range before entering.

3.3.2.2 Case of Resident WA-G

Resident WA-G was observed moving to the restroom a total of 33 times across all phases. Of these, there were three instances (9%) where they were guided by a third party, and 30 instances (91%) where they moved independently. Among the three restrooms in the unit, the locations of restroom use during independent movement were T1 nine times, T2 eighteen times, and T3 three times, indicating a tendency to use the restroom closest to their current location.

Resident WA-G's wandering behavior was observed only in Ph3. On Day 8 at 11:43, while heading to T2, they were seen mistakenly opening their own room door. Subsequently, a staff member who was observing the sequence of actions guided them to T2. On the other hand, at 10:58 on Day 11 of Ph4, resident WA-G was observed moving to the door of T2, visually confirming the text on the sign from close range before entering. Resident WA-G frequently moved to the restroom independently across all phases, indicating their ability to do so autonomously. Additionally, no wandering behavior was observed in Ph2, and there was only one instance in Ph3, suggesting that factors other than the presence of restroom signs may have contributed to the wandering behavior.

3.3.2.3 Case of Resident KA-C

Resident KA-C was confirmed to have moved to the restroom 21 times across all phases. Of these, there were 12 instances (57%) where they were guided by a third party and nine instances (43%) where they moved independently, indicating a tendency to be guided to the restroom by staff. Among the two restrooms in the unit, the locations of restroom use during independent movement were T1 six times and T2 three times, indicating a tendency to use T1, which is closest to their room.

Resident KA-C's wandering behavior was observed in Ph2 and Ph3. Although the number of times they moved to the restroom independently was low, the occurrence rate of wandering behavior was high, ranging from 33% to 100%. Additionally, all instances of wandering behavior occurred when using T1. In Ph2, at 17:12 on Day 5, resident KA-C was observed stopping on their way from their room to T1, appearing to become confused with the adjacent bathroom door. In Ph3, at 12:39 on Day 7, while heading from their room to T1, the resident mistakenly opened the door to the bathroom adjacent to the restroom, realized the mistake, and then proceeded to the restroom. On the other hand, no wandering behavior was observed in Ph1 and Ph4.

4 Discussion on the Guiding Effect of Residents' Room Signs and Restroom Signs

4.1 Characteristics of Wandering Behavior and the Significance of Signs

Based on the results of this study, we analyze the characteristics of wandering behavior observed in each resident. During phases Ph2 and Ph3, residents initially moved in the direction of their own rooms or restrooms. However, upon reaching the vicinity of their intended destination, they exhibited difficulty distinguishing their own doors from other adjacent doors. This led to behaviors such as searching for their own rooms or attempting to enter other residents' rooms or bathrooms. In other words, the residents had a general sense of the location and direction of their intended destinations and were able to reach the area around these destinations correctly. However, in the final process of selecting the correct door, they were unable to identify the precise location. As contributing factors to this phenomenon, it is considered that not only the disorientation and visuospatial cognitive impairment7 caused by dementia but also the physical environment with consecutive similar doors exacerbate wandering behavior. In contrast, the reduction in wandering behavior observed in phases Ph1 and Ph4 suggests that the display of residents' room signs and restroom signs effectively serves as cues, helping elderly individuals with dementia accurately identify the precise location of their intended destinations. Additionally, the survey results showed that in phases Ph2 and Ph3, no residents exhibited wandering behavior in both their rooms and restrooms simultaneously, suggesting that the recognition of the locations of their rooms and restrooms is not lost simultaneously.

4.2 Differences in Guiding Effect of Displayed Content

In the behavioral observation survey, differences in the displayed content resulted in varying levels of effectiveness. This section examines the impact of these differences in displayed content and the contributing factors.

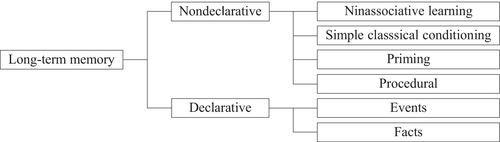

4.2.1 Relationship Between Understanding and Remembering Sign

To understand the meaning of the content indicated by residents' room signs and restroom signs, it is important for the recipients to retain their memory of experiences and knowledge related to the content. Memory can be classified based on retention time and content. In terms of time-based classification within the field of clinical neurology, memory is divided into immediate memory, recent memory, and remote memory (which corresponds to long-term memory in psychology) based on the time elapsed from the stimulus to recall (Figure 2). In terms of content-based classification, long-term memory is broadly categorized into declarative memory, which includes memories that can be consciously recalled as images or language, and non-declarative memory, which includes memories that cannot be consciously recalled or articulated (Figure 3). Furthermore, declarative memory is subdivided into event memory (episodic memory), which corresponds to unique personal experiences or single events, and facts memory (semantic memory), which involves knowledge that is typically acquired through repeated similar experiences, such as the meanings of words, objects, and social conventions.

The content indicated by residents' room signs and restroom signs is recognized as corresponding to their own room or restroom by linking to either the recipient's episodic memory or semantic memory. Which type of memory the signs engage with depends on the nature of the content displayed. The study by Namazi [4] mentioned in Section 1.2 uses items based on residents' experiences, such as photos of loved ones, items related to work or leisure, and memorabilia from World War II. These items primarily connect to episodic memory and thereby contribute to the recognition of one's own room. Furthermore, the study reported that items evoking older memories were more effective in triggering recall and aiding in the identification of residents' rooms. This can be attributed to the retrograde amnesia of episodic memory, which is characteristic of Alzheimer's disease. On the other hand, the text-based signs used in this study, such as residents' names and the word “restroom,” are thought to be linked to semantic memory. This connection helps individuals understand what the room or restroom represents, leading to the recognition that it is their intended destination. Episodic memory and semantic memory are affected differently depending on the type of dementia. In Alzheimer's disease, which is prevalent among elderly individuals with dementia, episodic memory is impaired from an early stage, whereas semantic memory tends to remain relatively intact even in individuals with moderate dementia. In contrast, in semantic dementia,8 semantic memory is impaired, particularly affecting less frequent and less familiar information early on, while episodic memory and visuospatial cognitive functions are preserved.9

According to Asada's report [12], in urban areas of Japan, approximately 68% of dementia patients have Alzheimer's disease, while about 1% have frontotemporal lobar degeneration, the cause of semantic dementia. Therefore, installing signs that connect to semantic memory is likely to be more effective in accommodating a larger number of elderly individuals with dementia. On the other hand, it is important to differentiate between using signs and items based on episodic memory and semantic memory according to the preferences and circumstances of elderly individuals with dementia. Given that each resident's episodic and semantic memories vary, it is crucial to understand and assess their memory retention status and to display signs that they can appropriately recognize and interpret.

4.2.2 Display Content With Expected Guiding Effect

Even with signs linked to the same semantic memory, different effects were observed based on the content displayed. Resident WA-B, who exhibited wandering behavior while heading to their rooms, and the three residents who exhibited wandering behavior while heading to the restroom were all able to reach their intended destinations appropriately in Ph1 and Ph4, where residents' names and text-based signs were displayed. The guiding effect observed with these signs can be attributed to the method of directly displaying the names of the room users or room names in text, which is easily understood by elderly individuals with dementia and closely linked to their semantic memory. Additionally, terms like residents' names and “restroom” are frequently used in daily communication, making them less likely to be impaired and easier for individuals with moderate dementia to recognize.

4.2.3 Display Content With Which It Is Difficult to Achieve Guiding Effect

In Phase 3, where only pictograms were displayed for restroom signs, there was no improvement observed in residents WA-A and KA-C. The use of pictograms alone did not provide sufficient information for moderately demented elderly individuals to identify the restroom. This suggests that the residents either lacked the knowledge that the pictogram represented a restroom or were unable to interpret the sign correctly, thus failing to trigger their semantic memory.

Pictograms representing restrooms, like text-based signs such as “restroom,” are also stored in semantic memory. These pictograms were first introduced during the 1964 Tokyo Olympics and gradually became common in public spaces following the 1970 Osaka Expo.10 Furthermore, the current standardized pictograms were established in 2002. Therefore, for the elderly dementia patients surveyed, these pictograms, established mostly after their middle age, were relatively unfamiliar, and it is likely that they had not developed strong semantic memory associations with them. Additionally, it has been reported that elderly individuals with dementia tend to recognize only the superficial information of icons, signs, and marks with artificially assigned meanings and often do not grasp their true significance.11 Based on the above, it is evident that pictograms, which have an artificially assigned meaning for restrooms, are difficult for elderly individuals with dementia to understand. This also suggests that one of the strengths of pictograms—intuitive information transmission through images that do not rely on language knowledge—was not effectively realized in this context. In Ph3, where different flower pictures were displayed for each room as substitutes for residents' names, there was no improvement in the wandering behavior of resident WA-B. In this study, no training or learning interventions regarding the newly installed pictures were conducted during the transition to Ph3. As a result, residents had to learn and internalize the meanings of these pictures on their own. Therefore, the pictures did not function as effective indicators of room locations and, like the pictograms, were likely recognized only at a superficial level.

This suggests that introducing signs that are not linked to memory in isolation during facility planning may result in signs that hold no meaning for residents. On the other hand, Hanley [5] reported improvements in orientation when combining orientation training with the use of three-dimensional pictures or objects as signs. Therefore, for signs with artificially assigned meanings, such as the pictograms and pictures that did not show effectiveness in this study, further research is needed to explore the guiding effect when appropriate training and learning periods are provided.

5 Conclusion

5.1 Guiding Effect of Signs in Previous Studies

Namazi [4] reported that for individuals with moderate dementia, items connected to their memories before the progression of dementia helped in identifying their rooms. Items that evoked childhood memories were particularly effective in triggering recall. However, items not associated with memory, while interesting to residents, did not serve as effective location cues. Hanley [5] found that combining orientation training with the installation of signs improved orientation, whereas the installation of signs alone was less effective. Amemiya [6] examined the impact of door color changes on the responses of individuals with dementia. While changes in door color did not alter their reactions, keeping doors open led to behaviors such as peering inside or entering the rooms. On the other hand, while there have been no direct studies on the effectiveness of room and restroom signs for dementia patients in group homes in Japan, a series of studies conducted by Tanaka [7-10] reported high staff evaluations regarding the guiding effect of signs displaying “residents' names,” “residents' personal mementos,” and “restroom” (room name text labels). These studies suggest the potential guiding effect of room and restroom signs based on their findings.

5.2 Guiding Effect of Resident's Room and Restroom Signs for Dementia Patients

The behavioral observation survey revealed that only five residents exhibited wandering behavior when moving to their rooms or restrooms. Each of these residents showed wandering behavior in only one of the two contexts, either while moving to their room or to the restroom, suggesting that their recognition of the locations of their rooms and restrooms was not simultaneously impaired.

When analyzed by the progression of dementia, residents with mild cognitive impairment were able to recognize the locations of their intended destinations regardless of the presence of room or restroom signs. Many of the severely impaired residents were not capable of independent living and required guidance from staff, thus rarely having the opportunity to identify room or restroom signs on their own. In contrast, residents with moderate impairment, who exhibited memory and orientation issues but were still capable of moving to their rooms or restrooms independently, showed a reduction in wandering behavior when specific room or restroom signs were displayed. These findings are consistent with reports by Namazi [4].

Observing the behaviors of residents who exhibited wandering, it was noted that they had a general sense of the location and direction of their intended destination and were able to reach the area around it correctly. However, in the final process of selecting the correct door, they were unable to identify the precise location, which led to wandering behavior. In contrast, when specific residents' room signs or restroom signs were displayed, they served as cues that helped residents accurately identify the precise location of their intended destinations.

5.3 Differences in Guiding Effect Based on Sign Content

The effectiveness of guiding dementia patients using residents' room signs and restroom signs depends on the patients' ability to retain the memory necessary to understand the meaning of the items or words displayed. It is also crucial that the signs are designed in a way that dementia patients can read and connect to their existing memories.

The display of residents' names on room signs and the use of text such as “restroom” on restroom signs were found to have a guiding effect on individuals with dementia. Directly labeling the names of room users or facilities in text is easily understood by dementia patients and is more likely to be connected to their semantic memory. On the other hand, pictograms used for restroom signs and flower pictures used for residents' room signs, which did not connect to the residents' memories, did not exhibit any guiding effect. The unfamiliarity of pictograms to the residents' age group and their tendency to only recognize superficial information without understanding the true meaning are likely reasons for this. Additionally, the flower pictures did not function as effective location cues because no training or interventions were provided to help residents learn the meaning of the pictures. Consequently, like the pictograms, the flower pictures were only recognized at a superficial level and did not aid in guiding the residents.

On the other hand, Hanley [5] reported that combining orientation training with the installation of three-dimensional pictures or objects as signs led to improvements in orientation. This suggests that even though pictograms and pictures did not show any guiding effect in this study, further research is needed to explore the potential guiding effect when appropriate training and learning periods are provided.

Acknowledgments

In writing this study, I would like to express my heartfelt gratitude to Dr. Yukiko Mori, M.D. from the Department of Neurology Showa, University School of Medicine, for her repeated valuable advice. I would also like to extend my sincere thanks to the staff, residents, and their families of the group homes who understood and cooperated with the implementation of the survey. This study is a collaborative research project conducted with Saho Usuki, who was affiliated with the Katsumata Laboratory, Department of Architecture, Faculty of Engineering, Tokyo City University.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Endnotes

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.