Effects of work–family life support program on the work–family interface and mental health among Japanese dual-earner couples with a preschool child: A randomized controlled trial

Abstract

Objectives

This study examined the effectiveness of a newly developed work–family life support program on the work–family interface and mental health indicators among Japanese dual-earner couples with a preschool child(/ren) using a randomized controlled trial with a waitlist.

Methods

Participants who met the inclusion criteria were randomly allocated to the intervention or the control groups (n = 79 and n = 85, respectively). The program comprised two 3-h sessions with a 1-month interval between them and provided comprehensive skills by including self-management, couple management, and parenting management components. The program sessions were conducted on weekends in a community center room with 3–10 participants. Outcomes were assessed at baseline, 1-month, and 3-month follow-ups. Primary outcomes were work–family balance self-efficacy (WFBSE), four types of work–family spillovers (i.e., work-to-family conflict, family-to-work conflict, work-to-family facilitation, and family-to-work facilitation), psychological distress, and work engagement reported by the participants.

Results

The program had significantly pooled intervention effects on WFBSE (P = .031) and psychological distress (P = .014). The effect sizes (Cohen's d) were small, with values of 0.22 at the 1-month follow-up and 0.24 at the 3-month follow-up for WFBSE, and −0.36 at the 3-month follow-up for psychological distress. However, the program had nonsignificant pooled effects on four types of work–family spillovers and work engagement.

Conclusions

The program effectively increased WFBSE and decreased psychological distress among Japanese dual-earner couples with a preschool child(/ren).

1 INTRODUCTION

With changes in family structures and increasing participation of women in the workforce, the number of dual-earner couples is steadily increasing.1 With this trend, employees are having to work additional hours beyond their traditional work timings more often to fulfill the demands of their roles as a spouse, parent, or caregiver.2

As such couples have to play the roles of both workers and spouses, qualities of their work and family life become unequivocally interconnected. Initial research on the work–family interface had focused on work–family conflict, or how involvement in one role interferes with participation in another (i.e., work-to-family conflict: WFC; family-to-work conflict: FWC).3 In the early 2000s, researchers began to focus on work–family enrichment or how involvement in one role improves the functioning of another (i.e., work-to-family facilitation: WFF; family-to-work facilitation: FWF).4 These spillover theories5, 6 assume that the relationship between the two life domains is bidirectional (i.e., work-to-family and family-to-work) in terms of affect and skills and that its nature is both negative (i.e., work–family conflict) and positive (i.e., work–family enrichment). Previous meta-analytic reviews showed that a person's WFC and FWC have had adverse effects on their psychological and physical health,7 whereas an individual's WFF and FWF have had favorable effects on them.6 Thus, managing the interface between work life and family life plays an important role in determining one's well-being.

However, for dual-earner couples, considering the boundary between the two life domains for only one individual is not enough. The marital relationship also plays a critical role in one's well-being.8 Thus, spouses are increasingly recognized as shapers of employees' work engagement,9 family satisfaction,10 happiness,11 and work outcomes (e.g., absenteeism).12 Furthermore, for those with children, couples' parent–child relationships also play a crucial role since the parenting role and satisfaction are embedded within the large context of marital quality.13 As parenting stress during the preschool period of a child is higher compared with other periods of the child's development,14 a comprehensive understanding of the multiple roles of workers, spouses, and parents is crucial for well-being among dual-earner couples during the child-rearing period.

Previous work–family life support programs have focused exclusively on the role of spouses or parents.8, 13 For example, Zemp et al.'s randomized controlled trial (RCT)8 among dual-earner couples focused on the marital relationship but did not deal with their work life or parenting. As dual-earner couples with child face demands from the work as well as the relationship domains (i.e., marital relationships and parent–child relationships), a comprehensive program to enhance skills to fulfill multiple roles of workers, spouses, and parents are highly needed.

1.1 The current study

This study examined the effectiveness of a newly developed work–family life support program on the work–family interface and mental health indicators among Japanese dual-earner couples with a preschool child(/ren) using an RCT design.

For this study, in terms of work–family interface indicators, we focused on work–family balance self-efficacy (WFBSE: the belief in our own ability to successfully balance work and family roles)15 along with four types of work–family spillovers (i.e., WFC, FWC, WFF, and FWF). Existing empirical research has shown that WFBSE is negatively associated with future WFC,16 suggesting that it is a determinant of actual change of spillovers. In terms of mental health, we focused on psychological distress and work engagement for negative and positive aspects of mental health. We hypothesized that participants in the intervention group would have greater improvement in WFBSE, spillovers, alleviating psychological distress, and work engagement than those in the control group.

Furthermore, we also explored whether the effectiveness of the program might be moderated by the initial levels of WFBSE. For instance, participants with high WFBSE at baseline would have already achieved a good work-family interface. Thus, we can assume that the program could be less effective among those with high WFBSE at baseline (i.e., ceiling effect). However, according to Bandura,17 self-efficacy is expected to contribute to individuals' cognitive strategies, their choice of behaviors, their affective states, and their persistence when faced with obstacles. Thus, it can be also assumed that the program could be more effective among those with high WEBSE at baseline. Hence, whether a low or high WFBSE at baseline would affect the outcomes positively or negatively should be investigated by subgroup analysis.

2 METHODS

2.1 Trial design

This study used an RCT study design. The allocation ratio of the intervention group to the control group was 1:1. The manuscript was written according to the Consolidated Standard of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) checklist.18

2.2 Participants

Participants were recruited through six institutions (i.e., Nagasaki University, Nagoya University, Seirei Social Welfare Community, Sinshu University, Fukui University, and Kitasato University) across Japan from September 2018 to May 2019. Study coordinators for each institute sent emails, flyers, and newsletters to potential participants. Inclusion criteria for participants were as follows: (1) aged between 20 and 65 years, (2) having a preschool child(/ren), (3) dual-earner couples, and (4) living with a partner. The exclusion criterion for this study was: taking childcare leave. Each institution held a briefing session for those who were interested in participating in this research, whereby the study's objectives and procedures were explained with the help of presentations and information pamphlets. Those who agreed to participate filled in the consent form and answered the web-based self-report questionnaire at baseline.

2.3 Interventions

The program was developed with the help of a literature review, together with a discussion with occupational health and human resource management professionals, along with interviewing dual-earner couples with preschool child(/ren). One of the unique features of the program was that it comprised the following three types of management: self-management (i.e., anger management and career development), couple management (i.e., couple coping and communication with partners), and parenting management. Participants acquired knowledge and skills on three types of management through various case study videos, lectures, individual works, role plays, and group discussions.

This program comprised two 3-h sessions with a 1-month interval between them. The program was provided by facilitators, who were all support professionals, such as clinical psychologists, industrial counselors, occupational health nurses, public health nurses, social workers, and occupational health physicians. All facilitators received two 1-day training sessions before delivering the program. The program sessions were conducted on weekends in a community center room with 3–10 participants. Childcare support was provided for participants if they desired it. Participants were provided with a textbook, handouts of PowerPoint presentations, and worksheets for exercise and group discussion.

2.4 Program contents

Table 1 shows the timetable of the program. In the first part of the first session, the purpose, outline, and expected outcomes of the program were explained, and participants and facilitators introduced themselves. In the second part, the participants learned parenting management skills adopted by the Triple P program (Positive Parenting Program),19 which includes creating a safe and secure environment, modeling, praise for good behavior, dealing with unfavorable behaviors, and skin-to-skin contact. In the third part, after a 10-min break, the participants practiced low-back pain prevention exercises following a video regarding the same. In the fourth part, they learned anger management skills. After understanding the psychological mechanisms of anger, they tried to find their own triggers and signs of anger and were introduced to ways to manage their own anger such as mindfulness, counting, breathing, imaging, and positive self-talk. In the final part, participants shared the knowledge and insights they acquired during the session. During the 1-month break between the first and second sessions, they were encouraged to review the session with the help of textbooks and an e-learning website and to apply skills that they had learned in the first session to their daily life.

| Part | Contents | Components | Timetable (min) |

|---|---|---|---|

| First session | |||

| 1 | Introduction | 15 | |

| 2 | Parenting management skills | Parenting management | 85 |

| Break | 10 | ||

| 3 | Low-back pain prevention exercises | Self-management | 10 |

| 4 | Anger management | Self-management | 50 |

| 5 | Discussion | 10 | |

| Second session | |||

| 1 | Review | 10 | |

| 2 | Couple coping | Couple management | 70 |

| Break | 10 | ||

| 3 | Assertiveness | Couple management | 40 |

| 4 | Career development | Self-management | 40 |

| 5 | Closing | 10 | |

In the second session, the participants reviewed the contents of the first session and discussed their daily life application in the first part. In the second part, they learned the concept of “couple coping” to deal jointly with daily stressors as a unit. They were introduced to the psychological stress model,20 learned various kinds of problem- and emotion-focused coping strategies by couples, examined the current coping strategies, and prepared for more appropriate strategies to cope with stress in the future. During the 10-min break, a video on exercises to follow for low-back pain prevention was shown. In the third part, they were provided with assertiveness21 as a communication skill with their partners. They learned the concept of assertiveness and practiced honestly and effectively expressing their wants, thoughts, and feelings while empathically recognizing and respecting the same of their partner through role play.22 In the fourth part, they learned about career development with a long perspective. Adopting the concept of Life Career Rainbow,23 participants thought about the different roles at different stages of their life and considered how to improve the balance between work and private life through drawing Life Career Rainbow and a group discussion. In the final part, the participants reviewed the whole program and shared the knowledge and insights they acquired through the program. They were encouraged to review the program by textbook and e-learning website and to apply skills that they had learned in the first and second sessions to their daily life.

2.5 Control group conditions

The participants in the control group received no intervention from baseline to the 3-month follow-up survey. After the follow-up, the same intervention program was provided.

2.6 Outcomes

All outcomes were assessed using a web-based self-report questionnaire at baseline (T1), 1-month (T2: 1 month after completion of the intervention), and 3-month follow-ups (T3). The intervention started approximately 1 month after the baseline survey. Primary outcomes were WFBSE, four types of work–family spillovers (i.e., WFC, FWC, WFF, and FWF), psychological distress, and work engagement reported by the participants. Secondary outcomes were those reported by the spouses of the program participants. Please note that this article reports the findings of only the primary outcomes due to space limitations.

WFBSE was measured by six items developed by Lapierre et al.16 Items were scored on a 7-point scale, from 0 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree) and averaged to get an average score, creating a possible range of 0–6. Spillovers were measured with the Survey Work–Home Interaction-NijmeGen (SWING).24, 25 Items were scored on a 4-point scale, from 0 (never) to 3 (always) and averaged to get an average score, creating a possible range of 0–3. Psychological distress was assessed with 18 items using the corresponding subscales of the Brief Job Stress Questionnaire (BJSQ),26 reflecting a lack of vigor, irritability, fatigue, anxiety, and depression. Each item was scored on a 4-point scale, from 1 (almost never) to 4 (almost always), and averaged to get an average score, creating a possible range of 1–4. Work engagement was measured with the three-item version of the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (UWES),27 reflecting vigor, dedication, and absorption. Items were scored on a scale ranging from 0 (never) to 6 (always). The three items were summed to form one overall index of work engagement and averaged to get an average score, creating a possible range of 0–6.

2.7 Demographic characteristics

Demographic characteristics of the participants included age, gender, educational attainment, occupation, working hours per week, and the number of cohabitants in the family.

2.8 Sample size

The estimated sample size was 400 per group to detect an effect size (Cohen's d) of 0.20 or greater for psychological distress at an alpha error rate of .05 (two-tailed) and a beta error rate of .20 using the G*Power 3 program.28 No previous RCT studies have reported an effect size of the work–family life support program for psychological distress. However, a meta-analysis of observational studies29 showed that correlations were 0.35 between WFC and mental health (e.g., psychological distress) and −0.10 between WFF and mental health. Furthermore, in a previous RCT study on couple relationship education,8 the effect sizes for relationship satisfaction at the 3-month follow-up were 0.06 and 0.24 for women and men, respectively. Thus, it seemed reasonable to set 0.20 as an expected effect size in our program.

2.9 Randomization

Participants who fulfilled the inclusion criteria and completed a questionnaire at baseline were randomly allocated to the intervention or the control groups. A stratified permuted block randomization was conducted, and the participants were stratified into 16 strata according to gender and the eight areas where they live. An independent researcher generated a stratified permuted block random table, and an independent research assistant conducted the enrollment of participants and their allocation into groups. The stratified permuted block random table, which was password-protected, was blinded to the authors. Only the research assistant had access to it during the process of random allocation of participants.

2.10 Statistical methods

The data extracted were analyzed with linear mixed models, using SPSS 25. Linear mixed models are statistical models that contain both fixed and random effects and can handle nonbalanced data with missing entries and repeated observations.30 Intention-to-treat analysis was used.

For the main pooled analysis, a mixed model for repeated measures (MMRM) conditional growth model analysis with an autoregressive covariance matrix was conducted using a group (intervention and control) × time (baseline, 1-month, and 3-month follow-ups) interaction as an indicator of intervention effect. For sensitivity analysis, a similar MMRM, using the analysis of variance model, with an autoregressive covariance matrix was conducted. Additionally, the effect sizes (95% confidence intervals) were calculated using Cohen's d only among those who completed the questionnaire at 1-month and 3-month follow-up, although the effect sizes may be biased due to dropouts. Values of 0.2, 0.5, and 0.8 were generally interpreted as small, medium, and large effects, respectively.31

Subgroup analyses were conducted according to the levels of WFBSE (24 or lower score/higher than 25) at baseline, which was classified based on the median score.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Participant recruitment

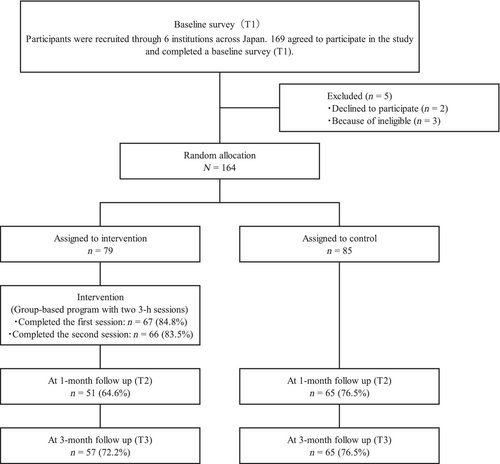

Recruitment and the baseline survey (T1) for this study were conducted from September 2018 to May 2019. The intervention started approximately a month after the baseline survey. Follow-up surveys were conducted for the intervention and control groups at approximately 1 month (T2) and 3 months (T3), respectively, after completion of the intervention.

Figure 1 shows the participant flowchart. Participants were recruited from six institutions, and 169 agreed to participate in the study and completed a baseline survey (T1). However, five participants were excluded due to declination (n = 2) and ineligibility (n = 3). Of the total, 79 were randomly allocated to an intervention group and 85 to a control group. At the 1-month follow-up (T2), 51 (64.6%) participants in the intervention group and 65 (76.5%) in the control group completed the survey. At the 3-month follow-up (T3), 57 (72.2%) participants in the intervention group and 65 (76.5%) in the control group completed the survey.

3.2 Baseline characteristics

Table 2 shows the demographic characteristics of the participants. In both groups, most participants were female, and they completed an equivalent of university or higher education. Among the participants, the most frequent occupations were professional, followed by clerical, service, and sales.

| Intervention group (n = 79) | Control group (n = 85) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | Mean | SD | n | % | Mean | SD | |

| Age | 36.9 | 5.0 | 37.1 | 4.7 | ||||

| Gender | ||||||||

| Females | 68 | 86.1 | 72 | 84.7 | ||||

| Males | 11 | 13.9 | 13 | 15.3 | ||||

| Education | ||||||||

| High school | 16 | 20.3 | 14 | 16.5 | ||||

| Junior college | 12 | 15.2 | 15 | 17.6 | ||||

| University | 41 | 51.9 | 49 | 57.6 | ||||

| Graduate school | 10 | 12.7 | 7 | 8.2 | ||||

| Occupation | ||||||||

| Professional/technical | 49 | 62.0 | 44 | 51.8 | ||||

| Management | 1 | 1.3 | 0 | 0.0 | ||||

| Clerical | 20 | 25.3 | 26 | 30.6 | ||||

| Sales | 3 | 3.8 | 5 | 5.9 | ||||

| Service | 5 | 6.3 | 6 | 7.1 | ||||

| Product | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 1.2 | ||||

| Others | 1 | 1.3 | 3 | 3.5 | ||||

| Working hours (/w) | 35.2 | 13.3 | 35.6 | 16.0 | ||||

| Number of cohabitants | 2.9 | 1.0 | 3.2 | 1.1 | ||||

- Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation.

3.3 Effects of work–family life support program on each outcome variable

Table 3 shows the means and SDs of the outcome variables at baseline (T1), 1-month (T2), and 3-month (T3) follow-ups in the intervention and the control groups.

| Outcome variables | Intervention | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | T2 | T3 | |||||||

| n | Mean | SD | n | Mean | SD | n | Mean | SD | |

| Work–family balance self-efficacy | 79 | 3.98 | 0.95 | 51 | 4.71 | 0.98 | 57 | 4.66 | 1.07 |

| Work-to-family conflict | 79 | 0.95 | 0.62 | 51 | 0.82 | 0.64 | 57 | 0.80 | 0.63 |

| Family-to-work conflict | 79 | 0.32 | 0.43 | 51 | 0.34 | 0.43 | 57 | 0.33 | 0.52 |

| Work-to-family facilitation | 79 | 1.34 | 0.61 | 51 | 1.50 | 0.57 | 57 | 1.47 | 0.65 |

| Family-to-work facilitation | 79 | 1.56 | 0.64 | 51 | 1.59 | 0.66 | 57 | 1.54 | 0.71 |

| Psychological distress | 79 | 2.14 | 0.53 | 51 | 2.07 | 0.57 | 57 | 1.97 | 0.51 |

| Work engagement | 79 | 3.24 | 1.19 | 51 | 3.35 | 1.75 | 57 | 3.28 | 1.30 |

| Outcome variables | Control | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | T2 | T3 | |||||||

| n | Mean | SD | n | Mean | SD | n | Mean | SD | |

| Work–family balance self-efficacy | 85 | 4.09 | 1.16 | 65 | 4.49 | 1.06 | 65 | 4.38 | 1.17 |

| Work-to-family conflict | 85 | 0.94 | 0.76 | 65 | 0.78 | 0.58 | 65 | 0.84 | 0.64 |

| Family-to-work conflict | 85 | 0.29 | 0.38 | 65 | 0.27 | 0.32 | 65 | 0.27 | 0.35 |

| Work-to-family facilitation | 85 | 1.40 | 0.65 | 65 | 1.40 | 0.63 | 65 | 1.35 | 0.69 |

| Family-to-work facilitation | 85 | 1.63 | 0.65 | 65 | 1.58 | 0.67 | 65 | 1.51 | 0.65 |

| Psychological distress | 85 | 2.09 | 0.54 | 65 | 2.07 | 0.50 | 65 | 2.17 | 0.57 |

| Work engagement | 85 | 3.50 | 1.21 | 65 | 3.53 | 1.22 | 65 | 3.29 | 1.06 |

- Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation.

Table 4 presents the estimated intervention effects on the outcome variables based on the mixed model analyses as well as effect sizes (Cohen's d). Both the growth curve models, and variance models including random intercept, and fixed effects are reported here. The program had a significant pooled effect on WFBSE (P = .031). A sensitivity analysis found that it had a marginally significant effect at 1-month (T2, P = .068) and a significant effect at 3-month (T3, P = .035) follow-up. The effect sizes were small, with values of 0.22 at T2 and 0.24 at T3. The program also had a significant pooled effect on psychological distress (P = .014). In a sensitivity analysis, it had a significant effect at T3 follow-up (P = .013). The effect size was small, with a value of −0.36. However, the program had nonsignificant pooled effects on four types of work–family spillovers and work engagement. Thus, our hypotheses were partially supported.

| Intervention (n = 79) | Control (n = 85) | Fixed effects | 95% CI | n | Cohen's d | 95% CI | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EM | SE | EM | SE | Lower | Higher | t | P | Lower | Higher | ||||

| Work–family balance self-efficacy | |||||||||||||

| T1 | 3.98 | 0.12 | 4.09 | 0.12 | |||||||||

| T2 | 4.73 | 0.14 | 4.51 | 0.13 | 0.32 | −0.02 | 0.67 | 1.84 | .068 | 116 | 0.22 | −0.15 | 0.58 |

| T3 | 4.70 | 0.14 | 4.40 | 0.13 | 0.41 | 0.03 | 0.78 | 2.13 | .035 | 122 | 0.24 | −0.11 | 0.60 |

| Pooled | 0.21 | 0.02 | 0.40 | 2.18 | .031 | ||||||||

| Work-to-family conflict | |||||||||||||

| T1 | 0.95 | 0.08 | 0.94 | 0.07 | |||||||||

| T2 | 0.86 | 0.09 | 0.86 | 0.08 | −0.01 | −0.21 | 0.19 | −0.09 | .925 | 116 | 0.06 | −0.30 | 0.43 |

| T3 | 0.86 | 0.08 | 0.92 | 0.08 | −0.07 | −0.27 | 0.13 | −0.68 | .498 | 122 | −0.06 | −0.42 | 0.29 |

| Pooled | −0.03 | −0.13 | 0.07 | −0.66 | .508 | ||||||||

| Family-to-work conflict | |||||||||||||

| T1 | 0.32 | 0.05 | 0.29 | 0.05 | |||||||||

| T2 | 0.35 | 0.05 | 0.27 | 0.05 | 0.05 | −0.09 | 0.18 | 0.70 | .488 | 116 | 0.18 | −0.19 | 0.55 |

| T3 | 0.33 | 0.05 | 0.27 | 0.05 | 0.03 | −0.13 | 0.19 | 0.42 | .673 | 122 | 0.14 | −0.22 | 0.49 |

| Pooled | 0.02 | −0.06 | 0.10 | 0.45 | .651 | ||||||||

| Work-to-family facilitation | |||||||||||||

| T1 | 1.35 | 0.07 | 1.40 | 0.07 | |||||||||

| T2 | 1.53 | 0.08 | 1.42 | 0.08 | 0.15 | −0.04 | 0.35 | 1.59 | .113 | 116 | 0.16 | −0.21 | 0.53 |

| T3 | 1.53 | 0.08 | 1.39 | 0.08 | 0.19 | −0.02 | 0.40 | 1.81 | .072 | 122 | 0.18 | −0.18 | 0.54 |

| Pooled | 0.10 | −0.01 | 0.20 | 1.87 | .064 | ||||||||

| Family-to-work facilitation | |||||||||||||

| T1 | 1.56 | 0.08 | 1.63 | 0.07 | |||||||||

| T2 | 1.62 | 0.09 | 1.61 | 0.08 | 0.08 | −0.12 | 0.29 | 0.78 | .439 | 116 | 0.01 | −0.36 | 0.37 |

| T3 | 1.61 | 0.08 | 1.54 | 0.08 | 0.14 | −0.08 | 0.37 | 1.27 | .207 | 122 | 0.03 | −0.32 | 0.39 |

| Pooled | 0.07 | −0.04 | 0.18 | 1.28 | .203 | ||||||||

| Psychological distress | |||||||||||||

| T1 | 2.14 | 0.06 | 2.09 | 0.06 | |||||||||

| T2 | 2.09 | 0.07 | 2.08 | 0.06 | −0.04 | −0.21 | 0.13 | −0.46 | .646 | 116 | −0.02 | −0.38 | 0.35 |

| T3 | 1.99 | 0.07 | 2.16 | 0.06 | −0.21 | −0.38 | −0.05 | −2.52 | .013 | 122 | −0.36 | −0.72 | 0.00 |

| Pooled | −0.10 | −0.19 | −0.02 | −2.48 | .014 | ||||||||

| Work engagement | |||||||||||||

| T1 | 3.24 | 0.14 | 3.50 | 0.14 | |||||||||

| T2 | 3.36 | 0.16 | 3.56 | 0.15 | 0.06 | −0.27 | 0.39 | 0.35 | .725 | 116 | −0.12 | −0.49 | 0.25 |

| T3 | 3.34 | 0.15 | 3.37 | 0.15 | 0.23 | −0.10 | 0.55 | 1.39 | .169 | 122 | −0.01 | −0.37 | 0.35 |

| Pooled | 0.11 | −0.05 | 0.27 | 1.37 | .174 | ||||||||

- Note: T1 = Baseline, T2 = 1-month follow-up, T3 = 3-month follow-up. Fixed effects of Pooled (interaction with time and intervention) were estimated by mixed models for repeated measures conditional growth model analyses. Fixed effects at T2 and T3 by intervention were estimated by mixed models for repeated measures ANOVA model analyses. Cohen's d was calculated among completers at baseline for each follow-up.

- Abbreviations: ANOVA, analysis of variance; CI, confidence interval; EM, estimated means; SE, standard errors.

3.4 Subgroup analysis

Tables 5 and 6 presents the estimated intervention effects on the outcome variables based on the mixed model analyses as well as effect sizes according to the levels of WFBSE. In the lower WFBSE group (Table 5), the program had a significant pooled effect on psychological distress (P = .012). A sensitivity analysis found a significant effect at the 3-month follow-up (P = .011). The effect size was medium, with a value of −0.49. Furthermore, the program had a marginally significant pooled effect on WLBSE (P = .058). A sensitivity analysis found a marginally significant effect at the 3-month follow-up (T3, P = .052). The effect size was medium, with a value of 0.51.

| Intervention (n = 42) | Control (n = 46) | Fixed effects | 95% CI | n | Cohen's d | 95% CI | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EM | SE | EM | SE | Lower | Higher | t | P | Lower | Higher | ||||

| Work–family balance self-efficacy | |||||||||||||

| T1 | 3.24 | 0.14 | 3.20 | 0.13 | |||||||||

| T2 | 4.43 | 0.16 | 4.06 | 0.15 | 0.33 | −0.13 | 0.79 | 1.42 | .158 | 64 | 0.37 | −0.13 | 0.86 |

| T3 | 4.45 | 0.16 | 3.91 | 0.15 | 0.51 | −0.01 | 1.02 | 1.97 | .052 | 68 | 0.51 | 0.02 | 0.99 |

| Pooled | 0.25 | −0.01 | 0.51 | 1.93 | .058 | ||||||||

| Work-to-family conflict | |||||||||||||

| T1 | 1.06 | 0.11 | 1.20 | 0.11 | |||||||||

| T2 | 0.92 | 0.12 | 1.01 | 0.11 | 0.05 | −0.23 | 0.33 | 0.37 | .712 | 64 | −0.04 | −0.53 | 0.46 |

| T3 | 0.95 | 0.12 | 1.07 | 0.12 | 0.02 | −0.28 | 0.32 | 0.14 | .893 | 68 | −0.07 | −0.55 | 0.40 |

| Pooled | 0.01 | −0.14 | 0.16 | 0.17 | .865 | ||||||||

| Family-to-work conflict | |||||||||||||

| T1 | 0.37 | 0.07 | 0.38 | 0.07 | |||||||||

| T2 | 0.35 | 0.08 | 0.32 | 0.07 | 0.03 | −0.18 | 0.23 | 0.27 | .787 | 64 | 0.04 | −0.46 | 0.53 |

| T3 | 0.42 | 0.08 | 0.33 | 0.08 | 0.09 | −0.15 | 0.34 | 0.76 | .448 | 68 | 0.22 | −0.26 | 0.69 |

| Pooled | 0.05 | −0.07 | 0.17 | 0.77 | .446 | ||||||||

| Work-to-family facilitation | |||||||||||||

| T1 | 1.30 | 0.10 | 1.20 | 0.10 | |||||||||

| T2 | 1.43 | 0.11 | 1.24 | 0.10 | 0.09 | −0.18 | 0.37 | 0.67 | .503 | 0.32 | −0.18 | 0.81 | |

| T3 | 1.44 | 0.11 | 1.26 | 0.10 | 0.08 | −0.20 | 0.36 | 0.59 | .560 | 64 | 0.30 | −0.18 | 0.77 |

| Pooled | 0.04 | −0.10 | 0.18 | 0.60 | .552 | 68 | |||||||

| Family-to-work facilitation | |||||||||||||

| T1 | 1.46 | 0.10 | 1.42 | 0.10 | |||||||||

| T2 | 1.45 | 0.11 | 1.45 | 0.10 | −0.05 | −0.31 | 0.22 | −0.34 | .733 | 64 | 0.08 | −0.41 | 0.57 |

| T3 | 1.49 | 0.11 | 1.35 | 0.11 | 0.10 | −0.21 | 0.41 | 0.63 | .529 | 68 | 0.23 | −0.24 | 0.71 |

| Pooled | 0.05 | −0.11 | 0.20 | 0.60 | .553 | ||||||||

| Psychological distress | |||||||||||||

| T1 | 2.24 | 0.09 | 2.22 | 0.08 | |||||||||

| T2 | 2.13 | 0.10 | 2.19 | 0.09 | −0.09 | −0.30 | 0.13 | −0.82 | .417 | 64 | −0.19 | −0.68 | 0.31 |

| T3 | 2.06 | 0.09 | 2.32 | 0.09 | −0.29 | −0.51 | −0.07 | −2.61 | .011 | 68 | −0.49 | −0.97 | −0.01 |

| Pooled | −0.14 | −0.25 | −0.03 | −2.58 | .012 | ||||||||

| Work engagement | |||||||||||||

| T1 | 3.21 | 0.19 | 3.28 | 0.18 | |||||||||

| T2 | 3.15 | 0.21 | 3.44 | 0.19 | −0.23 | −0.65 | 0.20 | −1.06 | .291 | 64 | −0.17 | −0.66 | 0.33 |

| T3 | 3.22 | 0.20 | 3.18 | 0.19 | 0.11 | −0.37 | 0.59 | 0.45 | .654 | 68 | 0.12 | −0.36 | 0.60 |

| Pooled | 0.05 | −0.20 | 0.29 | 0.39 | .699 | ||||||||

- Note: T1 = Baseline, T2 = 1-month follow-up, T3 = 3-month follow-up. Fixed effects of Pooled (interaction with time and intervention) were estimated by mixed models for repeated measures conditional growth model analyses. Fixed effects at T2 and T3 by intervention were estimated by mixed models for repeated measures ANOVA model analyses. Cohen's d was calculated among completers at baseline for each follow-up.

- Abbreviations: ANOVA, analysis of variance; CI, confidence interval; EM, estimated means; SE, standard errors.

| Intervention (n = 37) | Control (n = 39) | Fixed effects | 95% CI | n | Cohen's d | 95% CI | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EM | SE | EM | SE | Lower | Higher | t | P | Lower | Higher | ||||

| Work–family balance self-efficacy | |||||||||||||

| T1 | 4.82 | 0.13 | 5.14 | 0.13 | |||||||||

| T2 | 5.06 | 0.15 | 5.04 | 0.14 | 0.34 | −0.08 | 0.75 | 1.61 | .111 | 52 | 0.02 | −0.53 | 0.56 |

| T3 | 4.95 | 0.15 | 4.97 | 0.14 | 0.30 | −0.16 | 0.76 | 1.31 | .194 | 54 | −0.02 | −0.55 | 0.52 |

| Pooled | 0.16 | −0.07 | 0.39 | 1.41 | .163 | ||||||||

| Work-to-family conflict | |||||||||||||

| T1 | 0.81 | 0.09 | 0.62 | 0.09 | |||||||||

| T2 | 0.80 | 0.11 | 0.69 | 0.10 | −0.09 | −0.38 | 0.21 | −0.58 | .564 | 52 | 0.20 | −0.35 | 0.75 |

| T3 | 0.74 | 0.10 | 0.74 | 0.10 | −0.18 | −0.44 | 0.07 | −1.46 | .150 | 54 | −0.10 | −0.64 | 0.44 |

| Pooled | −0.09 | −0.22 | 0.03 | −1.46 | .151 | ||||||||

| Family-to-work conflict | |||||||||||||

| T1 | 0.26 | 0.05 | 0.19 | 0.05 | |||||||||

| T2 | 0.36 | 0.06 | 0.22 | 0.06 | 0.07 | −0.09 | 0.23 | 0.86 | .394 | 52 | 0.35 | −0.21 | 0.90 |

| T3 | 0.22 | 0.07 | 0.20 | 0.06 | −0.05 | −0.25 | 0.14 | −0.54 | .589 | 54 | −0.05 | −0.59 | 0.49 |

| Pooled | −0.02 | −0.12 | 0.08 | −0.41 | .682 | ||||||||

| Work-to-family facilitation | |||||||||||||

| T1 | 1.40 | 0.10 | 1.63 | 0.10 | |||||||||

| T2 | 1.64 | 0.11 | 1.64 | 0.11 | 0.23 | −0.04 | 0.49 | 1.71 | .091 | 52 | −0.05 | −0.60 | 0.49 |

| T3 | 1.65 | 0.12 | 1.55 | 0.11 | 0.32 | 0.01 | 0.63 | 2.05 | .044 | 54 | 0.06 | −0.47 | 0.60 |

| Pooled | 0.17 | 0.01 | 0.32 | 2.14 | .035 | ||||||||

| Family-to-work facilitation | |||||||||||||

| T1 | 1.67 | 0.11 | 1.88 | 0.10 | |||||||||

| T2 | 1.81 | 0.13 | 1.80 | 0.11 | 0.22 | −0.11 | 0.55 | 1.32 | .192 | 52 | −0.08 | −0.63 | 0.47 |

| T3 | 1.76 | 0.12 | 1.77 | 0.11 | 0.20 | −0.14 | 0.54 | 1.18 | .244 | 54 | −0.20 | −0.74 | 0.34 |

| Pooled | 0.11 | −0.06 | 0.27 | 1.26 | .212 | ||||||||

| Psychological distress | |||||||||||||

| T1 | 2.02 | 0.08 | 1.95 | 0.08 | |||||||||

| T2 | 2.06 | 0.10 | 1.96 | 0.09 | 0.02 | −0.24 | 0.29 | 0.17 | .863 | 52 | 0.21 | −0.34 | 0.76 |

| T3 | 1.92 | 0.10 | 1.98 | 0.09 | −0.14 | −0.40 | 0.13 | −1.04 | .304 | 54 | −0.21 | −0.75 | 0.33 |

| Pooled | −0.06 | −0.20 | 0.07 | −0.97 | .338 | ||||||||

| Work engagement | |||||||||||||

| T1 | 3.27 | 0.22 | 3.75 | 0.22 | |||||||||

| T2 | 3.62 | 0.25 | 3.70 | 0.23 | 0.41 | −0.13 | 0.94 | 1.52 | .134 | 52 | −0.08 | −0.63 | 0.47 |

| T3 | 3.49 | 0.24 | 3.60 | 0.23 | 0.37 | 0.00 | 0.75 | 1.99 | .053 | 54 | −0.15 | −0.69 | 0.39 |

| Pooled | 0.19 | 0.00 | 0.38 | 2.05 | .045 | ||||||||

- Note: T1 = Baseline, T2 = 1-month follow-up, T3 = 3-month follow-up. Fixed effects of Pooled (interaction with time and intervention) were estimated by mixed models for repeated measures conditional growth model analyses. Fixed effects at T2 and T3 by intervention were estimated by mixed models for repeated measures ANOVA model analyses. Cohen's d was calculated among completers at baseline for each follow-up.

- Abbreviations: ANOVA, analysis of variance; CI, confidence interval; EM, estimated means; SE, standard errors.

In the higher WFBSE group (Table 6), the program had a significant pooled effect on WFF (P = .035). A sensitivity analysis found a significant effect at the 3-month follow-up (T3, P = .044). The effect size was small, with a value of 0.06. Furthermore, the program had a significant pooled effect on work engagement (P = .045). A sensitivity analysis found a marginally significant effect at the 3-month follow-up (T3, P = .053). The effect size was small, with a value of −0.15.

4 DISCUSSION

This study examined the effectiveness of a newly developed work–family life support program among Japanese dual-earner couples with preschool child(/ren) using an RCT design. In line with our expectations, our program improved WFBSE and psychological distress. In this program, participants learned extensive knowledge and skills including self-management, couple management, and parenting management in a group setting. The group-based program could provide participants with the opportunity for social learning (e.g., observing, modeling, imitating the behaviors of other participants) and social influence (e.g., receiving positive feedback from other participants). Furthermore, an e-learning website could facilitate the retention of knowledge acquired in the program sessions and the application of the skills into their daily lives, which can help facilitate an improvement of belief in controlling their work–family balance32 and reduction of psychological distress.

It is notable that the favorable effects on WFBSE emerged at the 1-month follow-up and were maintained at the 3-month follow-up, whereas that on psychological distress was found only at the 3-month follow-up. This suggests that the program first improved WEBSE, followed by psychological distress. According to social and cognitive theory,33 self-efficacy determines how people think, behave, and feel. Thus, it took longer for a program to yield an effect on psychological distress than on self-efficacy.

It is also notable that a favorable intervention effect on psychological distress and WFBSE was more prominent in the lower WFBSE subgroup. This suggests that our newly developed program was more useful among those with lower WFBSE at baseline. For them, group sessions may have had a comforting and motivating effect because participants could share problems with a relevant peer group.34 Moreover, the group setting of the program could enable participants to meet challenges and create new and more positive experiences.35 Furthermore, the social interactions during the group session may have provided the participants with examples of good practice and with positive feedback on their individual approaches to work–family life.36 These have led to improvement in WFBSE and psychological distress, especially among those with lower WFBSE.

However, contrary to our expectations, we did not find any significant pooled intervention effects on four types of work–family spillovers such as WFC, FWC, WFF, and FWF. One possible reason for this was that we did not require participants' family members [i.e., partner or child(/ren)] to join the program, although our program included the skills of the partner relationship and parent–child relationship of the individual participant. We were concerned about the additional burden of joining the program for the participants and their family members. Thus, the lack of practice with family members during the session may have reduced the effectiveness of the program.

Another reason for the lack of intervention effect was that the follow-up period was too short.37 Although we found a favorable change in self-efficacy on work–family balance at 1-month (T2) and 3-month (T3) follow-ups, 3 months may not be enough to find the actual change in work–family balance. More time would thus be needed for participants to practice their acquired skills in their daily life and to detect a favorable change in their work–family spillovers. Thus, the study should be replicated with a longer follow-up period.

Furthermore, we also did not find a significant intervention effect on work engagement for the whole group. As our program did not include contents that focused directly on improving a positive, fulfilling, work-related state of mind, its effect might be relatively low.

4.1 Strength and limitations

This study has several strengths. First, it was an RCT that was able to control known and unknown confounding factors. Second, our program provided comprehensive skills including self-management, couple management, and parenting management. Third, the program was developed through not only a literature review but also a discussion with occupational health professionals and human resource management, and interviews with dual-earner couples with preschool child(/ren). Involving various stakeholders from the program development stage made the program more relevant to the target population and more committed. Fourth is regarding the delivery format of the program. The participants learned the skills in a group setting such as a role plays and group discussions, which provided them with the opportunity for social learning and social influence, leading to an improvement of WFBSE. Fifth, we prepared an e-learning website to facilitate the retention of knowledge acquired in the sessions and the application of the learned skills in their daily life. Sixth, a training session for facilitators was provided before starting the program. This procedure guaranteed the quality of facilitators in multiple institutes.

This study has several limitations. First, this study's sample size (N = 164) was modest compared with the planned number of 800 needed to detect an effect size of 0.20 or greater for psychological distress. Thus, the study had lower statistical power. Second, as mentioned above, the follow-up period was relatively short (i.e., 3 months). Given that the significant intervention effect on psychological distress was found only after 3 months, it may take longer to transfer the acquired skills into a real-life setting. The study should be replicated with a longer follow-up period. Third, the effect sizes were relatively small probably due to the characteristics of the participants. Specifically, previous studies on couple relationship training found more benefits among at-risk couples.38 Contrastingly, this study did not limit to at-risk couples. This may have reduced the effectiveness of the program. This speculation can be supported by the fact that the program was more effective in the lower WFBSE subgroup. Future studies may limit the participants with lower WFBSE to yield more strong effects. Fourth, the generalizability of this study is limited. This study was conducted in Japan, where the number of dual-earner couples is increasing1 and the balance between work and family life is becoming more difficult.39 Given that female employment rates in advanced countries are also increasing,40 our findings can be generalized to (at least) these countries. Even so, future research is needed to examine the cross-cultural effectiveness of our program. Finally, all outcomes in this study were assessed by self-report, which could have been affected by participants' perceptions or situational factors related to work and family. Further research should examine the intervention effect by using objectively measured outcomes.

5 CONCLUSIONS

This randomized controlled study examined the effectiveness of a newly developed work–family life support program among Japanese dual-earner couples with preschool child(/ren). The program effectively increased work–family balance self-efficacy and decreased psychological distress.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Akihito Shimazu was in charge of this study. Akihito Shimazu, Takeo Fujiwara, Noboru Iwata, Yoko Kato, Norito Kawakami, Nobuaki Maegawa, Mutsuhiro Nakao, Tetsuo Nomiyama, Miho Takahashi, Jun Tayama, and Izumi Watai conceived and designed this study. Akihito Shimazu, Takeo Fujiwara, Noboru Iwata, Yoko Kato, Norito Kawakami, Nobuaki Maegawa, Mutsuhiro Nakao, Tetsuo Nomiyama, Miho Takahashi, Jun Tayama, Izumi Watai, Makiko Arima, Tomoko Hasegawa, Ko Matsudaira, Yutaka Matsuyama, Yoshimi Miyazawa, Kyoko Shimada, Masaya Takahashi, Mayumi Watanabe, and Astushige Yamaguchi developed the intervention program as follows: (1) Miho Takahashi, Makiko Arima, and Ko Matsudaira developed Self-management program, (2) Yoko Kato and Izumi Watai developed Couple management program, (3) Takeo Fujiwara and Tomoko Hasegawa developed Parenting management program, (4) Mutsuhiro Nakao, Yoshimi Miyazawa, Mayumi Watanabe, and Astushige Yamaguchi created the PowerPoint files and movies, and (5) Akihito Shimazu, Noboru Iwata, Norito Kawakami, Nobuaki Maegawa, Tetsuo Nomiyama, Jun Tayama, Yutaka Matsuyama, Kyoko Shimada, and Masaya Takahashi reviewed all programs and materials. Akihito Shimazu, Yoko Kato, Norito Kawakami, Jun Tayama, Izumi Watai, Yutaka Matsuyama, Kyoko Shimada, Makiko Arima, Satomi Doi, Sachiko Hirano, Sanae Isokawa, Tomoko Kamijo, Toshio Kobayashi, Kichinosuke Matsuzaki, Naoko Moridaira, Yukari Nitto, Sayaka Ogawa, Mariko Sakurai, Natsu Sasaki, Mutsuko Tobayama, Kanako Yamauchi, Erika Obikane, Miyuki Odawara, Mariko Sakka, Kazuki Takeuchi, and Masahito Tokita conducted the intervention program in local settings. Noboru Iwata, Kazuki Takeuchi, Akihito Shimazu, and Yutaka Matsuyama conducted statistical analyses. Akihito Shimazu and Noboru Iwata wrote the first draft of the manuscript, and all other authors critically revised it. All authors read and approved the final paper.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This study was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS), Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (A) (grant number: 15H01832).

DISCLOSURE

Approval of Research Protocol: The Research Ethics Review Board of Graduate School of Medicine/Faculty of Medicine, The University of Tokyo approved the study procedures (reference number: 11174). Informed Consent: Each institution held a briefing session for those who were interested in participating in this research, whereby the study's objectives and procedures were explained with the help of presentations and information pamphlets. We explained that their participation was voluntary, and that they can withdraw consent for any reason. Those who agreed to participate filled in the consent form and answered the web-based self-report questionnaire at baseline. Registry and Registration No. of the Trial: UMIN Clinical Trials Registry (UMIN-CTR) (ID UMIN000034201). Animal Studies: N/A. Conflict of Interest: Prof. Akihito Shimazu (AS) received support in the form of a grant from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS), Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (A) (Grant Number: 15H01832). The remaining authors received no financial support or funding for this manuscript. The funding source had no role in the design, practice, or analysis of this study.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.