Prolonged sedentary time under the state of emergency during the first wave of coronavirus disease 2019: Assessing the impact of work environment in Japan

Teruhide Koyama and Kenji Takeuchi equally contributed to this work.

Abstract

Objectives

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak and the resulting state of emergency have restricted work environments, which may contribute to increased duration of sedentary behaviors. This study investigated the self-reported sedentary time of Japanese workers during and after the first state of emergency (April 7 to May 25, 2020) and examined differences in sedentary time after starting work from home and according to job type.

Methods

We used cross-sectional data from the Japan COVID-19 and Society Internet Survey, a web-based questionnaire survey conducted from August to September 2020 (n = 11,623; age range 15-79 years; 63.6% male). Prolonged sedentary time was calculated by subtracting the sedentary time after the state of emergency (defined as the normal sedentary time) from that during the emergency, with adjustments using inverse probability weighting for being a respondent in an internet survey.

Results

An increase in sedentary time of at least 2 hours was reported by 12.8% of respondents who started working from home during the state of emergency, including 9.7% of salespersons and 7.7% of desk workers. After adjusting for potential confounders, the multivariate-adjusted odds ratios (ORs) for a prolonged sedentary time ≥2 hours was significantly higher in respondents who started to work from home (OR: 2.14, 95% confidence interval: 1.78-2.57), and certain job types (desk workers; OR: 1.56, 95% CI: 1.27-1.91, salespersons; OR: 2.03, 95% CI: 1.64-2.51).

Conclusions

Working from home and non-physical work environments might be important predictors of prolonged sedentary time.

1 INTRODUCTION

The year 2020 brought unprecedented changes worldwide. On March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the novel coronavirus outbreak a pandemic; thereafter, many countries started lockdowns or requested nationwide stay-at-home orders for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infection control. With the ongoing lockdown or stay-at-home, large proportions of workers were instructed to stay home and work remotely, which, in turn, contributed to prolonged sedentary times.1 Organizations with and without previous experience in teleworking sent their employees home, thereby creating conditions for the most extensive mass teleworking experiment in history.2 More than 3.4 billion people in 84 countries were estimated to be confined to their homes in late March 2020, suggesting that millions of workers were temporarily exposed to telecommuting.3 In Japan, the first nationwide state of emergency was declared on April 16, 2020, in which the government recommended that organizations introduce working from home.4

A growing number of studies have demonstrated the association between prolonged sedentary time and negative health consequences including increased cardiovascular-specific events and overall mortality.5 We recently reported a positive association between sedentary time and cardiometabolic diseases such as hypertension, dyslipidemia, and diabetes6 in a general population sample. Thus, evidence suggests that reducing the amount of time spent on sedentary behavior can contribute to reducing morbidity and mortality. Regarding the appropriate limit to the amount of sedentary time, the WHO recommends 150 minutes of moderate-intensity or 75 minutes of vigorous-intensity physical activity per week. In addition, the WHO published guidance on how maintaining physical activity and reducing sedentary behavior during periods of self-isolation at home.7

Despite lockdowns and stay-at-home policies during the global COVID-19 epidemic, data are scarce regarding changes in sedentary behavior patterns. According to a previous internet survey that investigated changes in sedentary time in the following three groups: decrease, no change, or increase, about 30% of Japanese adults had prolonged sedentary time in February 2020, when the Japanese government requested the stay-at-home due to the COVID-19 pandemic, compared to the same period in the previous year.8 In this study; however, it is not clear whether the work environment affected sedentary time when stay-at-home and work from home were recommended during the state of emergency in Japan. Therefore, this study investigated the self-reported sedentary time of Japanese workers during and after the first state of emergency (April 7 to May 25, 2020) due to the COVID-19 pandemic and examined whether prolonged sedentary time differed according to the work environment.

2 MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 Study participants and setting

The Japan COVID-19 and Society Internet Survey (JACSIS) is launched in 2020 to investigate how social issues have changed such as health, medical care, work style, and economy under the COVID-19 pandemic. Some studies have already been published from the JACSIS study.9-11 We analyzed data from the JACSIS, a cross-sectional, web-based, self-reported questionnaire survey administered by a large Internet research agency (Rakuten Insight, Inc; https://in.m.aipsurveys.com) with access to more than 2.2 million panelists who encompassed a range of demographic characteristics: occupation, education level achieved, income level, and marital status. The survey requests were sent by the research agency to the panelists, who were selected by sex, age, and prefecture category using simple random sampling. The panelists who consented to participate in the survey accessed the designated website and responded to the survey. The panelists had the option of not responding to any part of the questionnaire and discontinuing the survey at any point. The survey was closed when the target numbers of respondents for each sex, age, and prefecture category were met. The participation rate for the survey was 12.5% (28 000 of 224 389 participants).

To validate the data quality, we excluded respondents showing discrepancies and/or artificial/unnatural responses.12, 13 Three question items were used to detect any discrepancies: “Please choose the second from the bottom,” “Select which drugs are used from the set of questions,” and “Choose which chronic diseases apply from the set of questions.” We excluded respondents who did not read the questions and/or chose every item in a list (n = 2518). The inclusion criteria were as follows: workers, except for those who were unemployed or on leave (working hours zero), and students, who answered the question items used in the analysis. Data from a total of 11 623 participants (7395 male and 4228 female) were included in the analysis.

The study was reviewed and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Osaka International Cancer Institute (no. 20084).

2.2 Outcomes

Participants recalled their average daily time spent sedentary in April to May 2020, during the first state of emergency, and in June to the time of the survey in 2020 (after the emergency). The self-reported times spent sedentary per day were categorized into the following original 11 categories (assigned average hours per day): none (0), <0.5 (0.25), 0.5 (0.5), 1 (1.0), 2 (2.0), 3 (3.0), 4-5 (4.5), 6-7 (6.5), 8-9 (8.5), 10-11 (10.5), and ≥12 (12) hours per day. After converting the sedentary time into continuous values as described previously,14 the prolonged sedentary time was calculated by subtracting the sedentary time after the declaration of the state of emergency from the sedentary time during the state of emergency. We treated the sedentary time after the state of emergency as the normal sedentary time for the following reasons. First, answering questions about the situation before the COVID-19 outbreak would increase recall bias; second, we could not go back to the time before the COVID-19 outbreak. Thus, we compared performed comparisons between normal conditions in the post-COVID-19 era and during the state of emergency. Previous studies reported associations between prolonged sedentary time of >2 hours and cardiometabolic diseases such as hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes, and accumulation of visceral fat, among Japanese people.6, 15 Accordingly, we entered the dichotomized variable of prolonged sedentary time (1 = ≥2 hours and 0 = <2 hours) as the outcome measure for the analysis into the logistic regression model.

2.3 Predictors

We used two predictor variables as work environment factors: job type (blue-collar workers with physically demanding jobs, desk workers such as those working on computers, and salespersons who mainly talked to people), and whether they started to work from home during the state of emergency.

2.4 Covariates

The covariates were age, sex, prefecture, education level achieved, annual household income, working hours per week, and the presence of morbidities; namely, hypertension, diabetes, asthma, bronchitis and pneumonia, atopic dermatitis, periodontal disease, caries (tooth decay), otitis media, angina pectoris, myocardial infarction, stroke (cerebral infarction or cerebral hemorrhage), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cancer and malignancies, chronic pain lasting for more than 3 months including back pain and headaches, depression, or psychiatric disorders other than depression.

2.5 Statistical analyses

Although Internet surveys have several advantages over traditional surveys, their greatest potential drawback is that they might not be representative of the population of interest because the subpopulation with access to the Internet might be specific. Previous studies have suggested that adjusted estimates using inverse probability weighting (IPW) obtained from a propensity score (calculated by logistic regression models using basic demographic and socioeconomic factors, such as education and housing tenure) from an Internet-based convenience sample provide similar estimates of parameters, or at least reduce the differences compared to population-based estimates.16-18 Therefore, IPW-adjusted estimates rather than simple Internet survey estimates are presented as the main results of this study. To correct for the selectivity of Internet-based samples, we used a population-based sample that was representative of the Japanese population from the Comprehensive Survey of Living Conditions of People on Health and Welfare (CSLCPHW).19 Data from two surveys (the Internet survey and CSLCPHW) were pooled and the weights (the inverse of propensity scores representing the estimated probability of participating in the survey) were calculated by fitting a logistic regression model using demographics, SES, and health-related characteristics to adjust for differences in respondents between the current Internet survey; that is, propensity scores. Using sex and age group stratifications (sex × age groups = 14 strata), we calculated the propensity score separately for each stratum.12, 13 Data from the 2016 CSLCPHW were used. The analyses were weighted to account for selection in an Internet survey.

Continuous variables were expressed as means and categorical data as sums and percentages. Intergroup comparisons were performed using chi-squared tests for categorical variables. We used logistic regression analyses to calculate the odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for prolonged sedentary time (treated as a dichotomized value) based on work environment factors. The multivariate-adjusted model included the following covariates: sex, age, prefecture, household income, education, chronic conditions, and working hours. A two-way analysis of variance was used to clarify the interaction between job types and start working from home on prolonged sedentary time ≥2 hours.

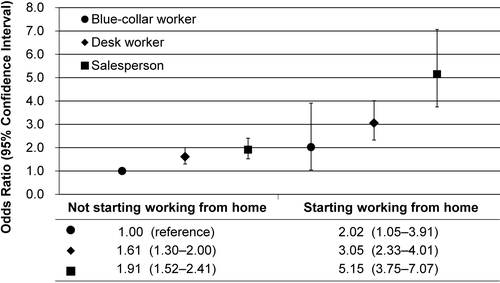

In addition, we evaluated whether a higher risk of prolonged sedentary time among subjects who started working from home varied according to their job type. For this, the study subjects were divided into the following six categories: (1) blue-collar workers who did not start working from home, (2) desk workers who did not start working from home, (3) salespersons who did not start working from home, (4) blue-collar workers who started working from home, (5) desk workers who started working from home, and (6) salespersons who started working from home.

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software, version 25 (IBM Japan), and statistical significance was set at P < .05.

3 RESULTS

Table 1 shows the sedentary times during and after the state of emergency. Little extension of sedentary hours per day was observed (males: −0.14; females: 0.10). Among the characteristics of the study participants, those who started work from home under the state of emergency had the longest extended sedentary time, with an average extended sedentary time of 16 minutes.

| Weighted na | % | Sedentary time (h/d) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| During the state of emergency | After the state of emergency | Mean difference | |||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||||

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 7395 | 63.6 | 3.73 | 3.20 | 3.87 | 3.30 | −0.14 |

| Female | 4228 | 36.4 | 4.45 | 3.27 | 4.35 | 3.19 | 0.10 |

| Age (y) | |||||||

| 15-29 | 2034 | 17.5 | 2.65 | 3.14 | 3.33 | 3.71 | −0.68 |

| 30-39 | 2197 | 18.9 | 4.05 | 3.24 | 3.98 | 3.18 | 0.07 |

| 40-49 | 2941 | 25.3 | 4.39 | 3.38 | 4.24 | 3.31 | 0.15 |

| 50-59 | 2313 | 19.9 | 4.42 | 3.07 | 4.32 | 3.00 | 0.10 |

| 60-69 | 1406 | 12.1 | 4.08 | 2.82 | 4.14 | 2.83 | −0.06 |

| 70-79 | 732 | 6.3 | 4.45 | 3.35 | 4.46 | 3.40 | −0.01 |

| Household income (million Japanese yen) | |||||||

| <2 | 1802 | 15.5 | 3.53 | 3.21 | 3.53 | 3.15 | 0.003 |

| 2-2.9 | 2604 | 22.4 | 3.57 | 3.03 | 3.47 | 2.94 | 0.10 |

| 3-3.9 | 2766 | 23.8 | 3.98 | 3.08 | 3.95 | 3.04 | 0.04 |

| 4-4.9 | 1430 | 12.3 | 4.87 | 3.22 | 4.78 | 3.20 | 0.09 |

| ≥5 | 3022 | 26.0 | 4.22 | 3.49 | 4.60 | 3.68 | −0.38 |

| Educational attainment | |||||||

| Up to junior high school graduate | 604 | 5.2 | 3.43 | 2.82 | 3.54 | 2.89 | −0.12 |

| Up to high school graduate | 4359 | 37.5 | 3.81 | 3.09 | 4.06 | 3.30 | −0.25 |

| Up to junior college graduate | 2139 | 18.4 | 3.96 | 3.18 | 3.90 | 3.05 | 0.07 |

| Up to college graduate | 3754 | 32.3 | 4.12 | 3.36 | 4.04 | 3.28 | 0.08 |

| Graduate degree | 779 | 6.7 | 4.93 | 3.78 | 4.82 | 3.80 | 0.10 |

| Chronic conditions | |||||||

| 0 | 7404 | 63.7 | 4.14 | 3.30 | 4.26 | 3.36 | −0.12 |

| 1 | 2371 | 20.4 | 4.37 | 3.11 | 4.30 | 3.05 | 0.07 |

| ≥2 | 1848 | 15.9 | 2.91 | 2.97 | 2.88 | 2.92 | 0.03 |

| Working hours (per week) | |||||||

| <20 | 1906 | 16.4 | 3.40 | 3.16 | 4.03 | 3.55 | −0.63 |

| 20-29 | 1848 | 15.9 | 2.74 | 2.69 | 2.86 | 2.64 | −0.12 |

| 30-39 | 2197 | 18.9 | 3.96 | 3.06 | 3.90 | 3.07 | 0.06 |

| 40-49 | 4266 | 36.7 | 4.52 | 3.24 | 4.43 | 3.23 | 0.09 |

| ≥50 | 1406 | 12.1 | 4.87 | 3.66 | 4.70 | 3.62 | 0.17 |

| Job type | |||||||

| Blue-collar worker | 3603 | 31.0 | 2.45 | 2.40 | 2.46 | 2.34 | −0.01 |

| Desk worker | 5195 | 44.7 | 5.44 | 3.38 | 5.40 | 3.36 | 0.04 |

| Salesperson | 2824 | 24.3 | 3.28 | 2.77 | 3.58 | 3.08 | −0.30 |

| Starting to work from home during the state of emergency | |||||||

| No | 9996 | 86.0 | 3.73 | 3.15 | 3.83 | 3.20 | −0.11 |

| Yes | 1627 | 14.0 | 5.62 | 3.37 | 5.36 | 3.39 | 0.26 |

- Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation.

- a We weighted the respondents of the Internet survey to be closer to a nationally representative sample of Japan.

Table 2 shows the distributions of prolonged sedentary times during and after the state of emergency. Among the participants, 7.2% experienced prolonged sedentary times of more than 2 hours. Regarding work environment factors, prolonged sedentary time was reported in 12.8% of those respondents who started work from home during the state of emergency, including 9.7% of salespersons, and 7.7% of desk workers. The frequencies of age groups, educational attainment, chronic conditions, working hours, and job type differed significantly different between respondents with sedentary times prolonged by more and less than 2 hours. Female and those who started to work from home during the state of emergency tended to belong to the group with sedentary time prolonged by >2 hours.

| Prolonged sedentary time | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <2 h | >2 h | ||||

| Weighted na | % | Weighted na | % | P value | |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 6944 | 93.9 | 451 | 6.1 | <0.01 |

| Female | 3848 | 91.0 | 380 | 9.0 | |

| Age (y) | |||||

| 15-29 | 1896 | 93.2 | 139 | 6.8 | <0.01 |

| 30-39 | 2016 | 91.8 | 181 | 8.2 | |

| 40-49 | 2704 | 91.8 | 241 | 8.2 | |

| 50-59 | 2127 | 92.0 | 184 | 8.0 | |

| 60-69 | 1342 | 95.4 | 64 | 4.6 | |

| 70-79 | 707 | 97.0 | 22 | 3.0 | |

| Household income (million Japanese yen) | |||||

| <2 | 1678 | 93.1 | 124 | 6.9 | 0.26 |

| 2-2.9 | 2426 | 93.1 | 180 | 6.9 | |

| 3-3.9 | 2582 | 93.3 | 185 | 6.7 | |

| 4-4.9 | 1306 | 91.5 | 121 | 8.5 | |

| ≥5 | 2800 | 92.7 | 222 | 7.3 | |

| Educational attainment | |||||

| Up to junior high school graduate | 572 | 95.4 | 28 | 4.6 | <0.01 |

| Up to high school graduate | 4062 | 93.1 | 300 | 6.9 | |

| Up to junior college graduate | 1974 | 92.4 | 162 | 7.6 | |

| Up to college graduate | 3446 | 91.9 | 305 | 8.1 | |

| Graduate degree | 738 | 95.4 | 36 | 4.6 | |

| Chronic conditions | |||||

| 0 | 6864 | 92.6 | 546 | 7.4 | <0.01 |

| 1 | 2180 | 92.1 | 186 | 7.9 | |

| ≥2 | 1748 | 94.6 | 99 | 5.4 | |

| Working hours (per week) | |||||

| <20 | 1767 | 92.5 | 143 | 7.5 | <0.01 |

| 20-29 | 1754 | 95.1 | 91 | 4.9 | |

| 30-39 | 2032 | 92.6 | 163 | 7.4 | |

| 40-49 | 3936 | 92.3 | 327 | 7.7 | |

| ≥50 | 1303 | 92.5 | 106 | 7.5 | |

| Job type | |||||

| Blue-collar worker | 4798 | 95.7 | 403 | 4.3 | <0.01 |

| Desk worker | 2550 | 92.3 | 274 | 7.7 | |

| Salesperson | 3444 | 90.3 | 154 | 9.7 | |

| Starting to work from home during the state of emergency | |||||

| No | 9371 | 93.8 | 622 | 6.2 | <0.01 |

| Yes | 1421 | 87.2 | 209 | 12.8 | |

- a We weighted the respondents of the Internet survey to be closer to a nationally representative sample of Japan.

Table 3 shows the estimated multivariate-adjusted ORs for prolonged sedentary time according to work environment factors. The adjusted OR of prolonged sedentary time was significantly higher in those who started work from home under the state of emergency than in those who did not start work from home patients (OR: 2.14, CI: 1.78-2.57). Likewise, the adjusted OR of prolonged sedentary time was significantly higher in desk workers (OR: 1.56, CI: 1.27-1.91) and salespersons (OR: 2.03, CI: 1.64-2.51) than in blue-collar workers. The results of two-way analysis of variance also showed that the interaction between job types and start working from home had a significant effect on prolonged sedentary time ≥2 hours (P = .002).

| Multivariate ORa | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|

| Job type | ||

| Blue-collar worker | Ref | |

| Desk worker | 1.56 | 1.27-1.91 |

| Salesperson | 2.03 | 1.64-2.51 |

| Starting to work from home during the state of emergency | ||

| No | Ref | |

| Yes | 2.14 | 1.78-2.57 |

- a The multivariate logistic regression model adjusted sex, age, prefecture, household income, education, chronic conditions, and working hours.

In addition, we examined the combined effect of starting working from home and job type on the risk of prolonged sedentary time (Figure 1). Compared with blue-collar workers who did not start working from home (the reference group), blue-collar workers, desk workers, and salespersons who started working from home had 2.0-fold, 3.1-fold, and 5.2-fold higher ORs of prolonged sedentary time, respectively.

4 DISCUSSION

The results of this study indicated that subjects who started working from home during the state of emergency and those who usually engaged in non-physical labor, such as sales and desk workers, were at increased risk of a sedentary time prolonged by >2 hours under the state of emergency during the COVID-19 outbreak. In addition, the combined analysis of those who started to work from home and job type demonstrated increased risks of prolonged sedentary time for those work types with non-physical labor. Importantly, this study provides the first evidence of an association between work environment and prolonged sedentary time under the state of emergency compared to normal conditions in the post-COVID-19 era in Japan.

Previous studies focused on the association between the work environment and the risk of prolonged sedentary time. In general, white-collar workers spend more time in a sitting position during work hours compared to blue-collar workers.20-23 Among white-collar workers, desk workers are among those with prolonged sedentary times; these workers are reported to be sedentary for over three-quarters of working hours per workday.24, 25 Furthermore, desk workers experience less brief-duration light-intensity activity during work hours compared to non-working time.25 Moreover, even during the COVID-19 outbreak, white-collar workers sat for more hours than blue-collar workers.26 Taken together, these findings indicate that white-collar workers are likely to be sedentary for a very high proportion of their working time and may be more likely to start working from home and spend more time sedentary. These findings are in agreement with those of the present study.

Few studies have examined changes in the work environment due to the COVID-19 pandemic. A recent study of 1,239 Japanese workers found that those who worked at home spent more time sitting during work hours than those working at their workplaces.27 The subjects of this previous study were recruited from seven prefectures in the Tokyo metropolitan area, which is traditionally considered a region with a high percentage of telecommuters (about 40%); in contrast, our study recruited subjects from all over Japan. Despite these differences in recruitment areas, the results of this previous study support our findings.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the change in the work environment is expected to lead to longer sedentary times that will, in turn, lead to decreased physical activity.28 This decreased physical activity negatively affects health. In the present study, the percentage of respondents who reported decreased exercise opportunities was higher among those with increased sitting time (data not shown). More research is needed on the diversity of work patterns from the perspective of occupational health, such as long-term follow-up studies to determine the effectiveness of interventions on work environments at home, including sit-stand desks, to reduce sedentary time while working at home.

The present study has several limitations. First, the cross-sectional design prevented us from ruling out the reverse causation that people with prolonged sedentary time tended to choose to work from home and to perform non-physical work. However, the chance of this being true is very low, since it is not practical to change the work environment to spend more time sitting. Second, the data used for this analysis were based on responses to an Internet survey, and there is a possibility of selection bias. To address this, our estimates were weight-adjusted to account for the use of an Internet-based survey, with a nationally representative sample. Thus, our results can be regarded as nationally representative, although they do not provide a perfect approximation. Third, this study used a self-administered questionnaire to evaluate sedentary time. Evidence from one review suggests that single-item self-reported measures generally underestimate sedentary time compared with device-based measures.29 However, the association between prolonged sedentary time and work environment observed in this study is considered to be robust because it is unlikely that this underestimation of sedentary time occurs in a biased manner in each category of work environment variables. Fourth, in this study, the sedentary time after the declaration of the state of emergency was treated as the normal sedentary time, but it is possible that the sedentary time after the state of emergency was prolonged than the original normal (before the COVID-19 epidemic) sedentary time due to the influence of the state of emergency. However, even under such an underestimation assumption, the fact that an association was found between the job type and the starting working from home and the prolongation of sedentary time may have acted to further increase the robustness of the results of this study.

5 CONCLUSIONS

There was little increase in sedentary time during the state of emergency; however, those who started working from home during the state of emergency and those who usually engaged in non-physical labor had a greater likelihood of increased sedentary time under the state of emergency. These findings emphasized the importance of not only encouraging people to not go outside but also reminding them to avoid working in a sitting position for long periods, even under lockdown and stay-at-home conditions.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data used in this study are not available in a public repository because they contain personally identifiable or potentially sensitive patient information. Based on the regulations for ethical guidelines in Japan, the Research Ethics Committee of the Osaka International Cancer Institute has imposed restrictions on the dissemination of the data collected in this study. All data enquiries should be addressed to the person responsible for data management, Dr. Takahiro Tabuchi at the following e-mail address: [email protected]

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was funded by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) KAKENHI Grants (grant numbers 17H03589, 19K10671, 19K10446, 18H03107, 18H03062), the JSPS Grant-in-Aid for Young Scientists (grant number 19K19439), Research Support Program to Apply the Wisdom of the University to tackle COVID-19 Related Emergency Problems, University of Tsukuba, and Health Labour Sciences Research Grant (grant numbers 19FA1005, 19FG2001). The findings and conclusions of this article are the sole responsibility of the authors and do not represent the official views of the research funders. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

DISCLOSURE

Approval of the research protocol: The Research Ethics Committee of the Osaka International Cancer Institute (no. 20 084) reviewed and approved the aims and procedures of this study. Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from all participants included in the study. Registry and the registration no. of the study/trial: N/A. Animal studies: N/A. Conflict of interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest for this article.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

TK, KT, and TT conceived the ideas; KT, JA, SK, YM, and TT collected the data; TK, KT, and YT analyzed the data; TK led the writing; and all the authors revised the manuscript and approved the final version of the manuscript.