A recognizable syndrome within CHARGE association: Hall-Hittner syndrome

CHARGE association was initially delineated as a non-random pattern of congenital anomalies that occurred together more frequently than one would expect on the basis of chance. It occurs with an estimated frequency of 1:10,000–15,000 and is a common cause of multiple congenital anomalies. Within the group of children diagnosed with CHARGE association, there is clearly a subgroup with such distinctive clinical characteristics that they appear to manifest a recognizable syndrome. The recent paper by Amiel et al. [2000] on temporal bone malformations patients with CHARGE syndrome presents compelling evidence that absence or hypoplasia of the semicircular canals should be considered a major diagnostic criterion for CHARGE syndrome. They present three patients with characteristic facial and ear findings in CHARGE association, but who lack both ocular colobomata and choanal atresia, and they assert that the specificity of the pattern of malformation in CHARGE association “is consistent enough to consider this a syndrome.” I agree that more precise diagnostic criteria seem to define a concise, recognizable syndrome within the group of patients with CHARGE association, and that these patients may manifest a disorder with a single pathogenetic basis, i.e., a syndrome.

CHARGE syndrome was first described in 1979 by Hall [1979] in 17 children with multiple congenital anomalies, who were ascertained because of choanal atresia. Hall emphasized that the ears were small, low-set, and deformed, without being microtic, and that this was frequently associated with cardiac defects, ocular colobomas (usually retinal), deafness, hypogenitalism in males, facial palsy, and postnatal growth problems with developmental delay. Hall indicated that this pattern of malformations raised “the distinct possibility that the associated anomalies may be part of a specific syndrome.” In the same year, Hittner [1979] described the same new syndrome in 10 children with colobomatous microphathalmia, congenital heart defects, developmental delay, facial palsy, pharyngeal incoordina- tion or paralysis, and external ear abnormalities with associated hearing loss.

Because these initial papers emphasized the occurrence of choanal atresia or ocular colobomata as key features in ascertaining children with this disorder, and because these features are not invariably present in all affected children, it took additional time and clinical observation to recognize the key importance of the characteristic ear and temporal bone morphology, as well as the characteristic cranial nerve dysfunction. Because these key findings are characteristically asymmetric in each patient, the facial phenotype of each individual patient is much more varied than typically seen in other syndromes. As time has gone on, most clinicians have come to recognize that this syndrome can be a cause for syndromic cleft lip or cleft palate, and also for syndromic tracheo–esophageal fistula. Experienced clinicians make this diagnosis most often using the characteristic ear morphology as a key clinical feature, and it makes good sense to emphasize the distinctive temporal bone findings described by Amiel et al. [2000] as an additional aspect of this feature. The current report by Martin et al. [2000] describing a male with a de novo chromosomal translocation between 2p14 and 7q21.11 and CHARGE association with choanal atresia and hypoplasia of both the semicircular canals and cochlear ducts demonstrates how useful a cranial CT scan can be in making this diagnosis. It also suggests 2 potential regions in our genome where the genetic basis for CHARGE may be located.

In 1981, Pagon et al. [1981] ascertained and reported children with either choanal atresia or coloboma and associated characteristic malformations, and first coined the acronym CHARGE association (Coloboma, Heart Defect, Atresia Choanae, Retarded Growth and Development, Genital Hypoplasia, Ear Anomalies/Deafness). In choosing this acronym, the intent was to emphasize that this clustering of associated malformations occurs more frequently together, than one would expect on the basis of chance, and that the etiology for the association between these defects was unknown. Preserving this original concept makes good sense because exceptional cases of a syndrome often yield useful information concerning genotype–phenotype correlations, and not every child with a given syndrome manifests even the most characteristic features (e.g., Williams-Beurens syndrome and supravalvular aortic stenosis). These exceptional cases often tell use quite a lot about how our genome works (or fails to work).

Another important contribution to the delineation of CHARGE as a multiple anomaly syndrome with a probable genetic basis was made in 1998, when Tellier et al. [1998] reviewed CHARGE association and reported 47 new cases. They emphasized several additional features, including asymmetric facial palsy, esophageal or laryngeal abnormalities, renal malformations, and facial clefts, and noted that distinctive neonatal brainstem dysfunction required complex management, often necessitating nasogastric or gastrostomy feeding, Nissen fundoplication, and tracheostomy. They also observed complete or partial semi- circular canal hypoplasia on temporal bone CT scans in all 12 patients evaluated, along with specific facial dysmorphic features, and significantly increased paternal age at the time of conception (suggesting a genetic cause).

Over the past 20 years, the specificity of this pattern of malformations has now reached the level that many clinicians and most parents in the CHARGE Syndrome Support Group now consider this entity to be a discrete recognizable syndrome with an as yet unknown genetic basis. With increasing experience, it has become clear that the CHARGE association criteria originally proposed by Pagon et al. [1981], and later revised by Mitchell et al. [1985], needed further refinement. In 1998, newly revised consensus diagnostic criteria, incorporating both major and minor features for CHARGE, were set forth by Blake and other colleagues on the CHARGE Syndrome Parent Support Medical Advisory Board [Blake et al., 1998]. They suggested these criteria (Table I) might ultimately define CHARGE syndrome as a recognizable syndrome within CHARGE association.

| Criterion | Includes | Frequency |

|---|---|---|

| Major | ||

| Coloboma | Coloboma of iris, retina, choroid, disc; microphthalmia | 80–90% |

| Choanal atresia | Unilateral/bilateral, membranous/bony, stenosis/atresia | 50–60% |

| Characteristic ear abnormalities | External ear (lop or cup shaped) | 90% |

| Middle ear (ossicular malformations, chronic serious otitis) | ||

| Mixed deafness, with temporal bone anomalies resulting in cochlear duct or semicircular canal hypoplasia | ||

| Cranial nerve dysfunction | I: Anosmia, VII: Facial palsy (unilateral or bilateral), VIII: Sensorineural deafness and vestibular problems, IX or X: Swallowing problems | 70–90% |

| Minor | ||

| Genital hypoplasia | Males: Micropenis, cryptorchidism | 70–90% |

| Females: Hypoplastic labia | 100% | |

| Both: Delayed, incomplete pubertal development | ||

| Developmental delay | Delayed motor milestones, hypotonia, MR | |

| Cardiovascular malformations | All types: usually conotruncal defects (esp. tetraology of Fallot with atrio-ventricular canal defects and aortic arch anomalies) | 75–85% |

| Growth deficiency | Short stature | 70% |

| Orofacial cleft | Cleft lip or palate | 15–20% |

| Tracheoesophageal-fistula | Tracheoesophageal defects of all types | 15–20% |

| Distinctive face | Characteristic face | 70–80% |

| Occasional Findings | ||

| Thymic/parathyroid hypoplasia | DiGeorge sequence without chromosome 22q11 deletion | Rare |

| Renal anomalies | Dysgenesis, horseshoe/ectopic kidney, hydronephrosis | 15–25% |

| Hand anomalies | Polydactyly, ectrodactyly, thumb hypoplasia | Rare* |

| Altered palmar flexion creases | 50% | |

| General appearance | Webbed neck | Rare |

| Sloping shoulders | Occasional | |

| Nipple anomalies (accessory or hypoplastic) | Rare | |

| Abdominal defects | Omphalocele | Rare |

| Umbilical hernia | 15% | |

| Spine anomalies | Scoliosis, hemivertebrae | Rare |

- * Rule out Tanes-Brocks syndrome.

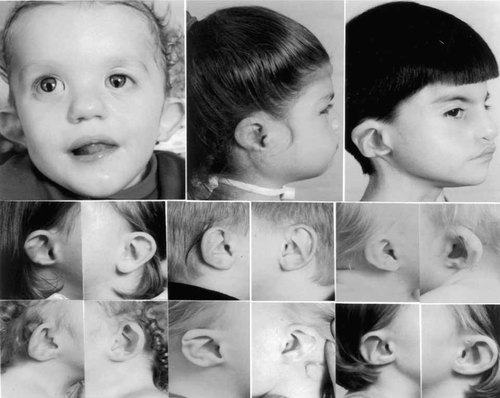

Major diagnostic criteria were those findings that occurred commonly in CHARGE, but were relatively rare in other conditions: coloboma, choanal atresia, cranial nerve involvement (particularly asymmetric facial palsy and neurogenic swallowing problems), and characteristic ear abnormalities (Fig. 1), that should now include both the distinctive asymmetrical auricular defects emphasized previously, as well as the temporal bone anomalies described by Amiel et al. [2000]. Minor diagnostic criteria which occur less frequently (or are less specific to CHARGE) include: heart defects, genital hypoplasia, orofacial clefting, tracheo–esophageal fistula, characteristic facial features, short stature, and developmental delay. Other occasional less-specific findings include: renal anomalies, thymic/parathyroid hypoplasia, hand and spine anomalies, webbed neck, sloping shoulders, nipple anomalies, and abdominal defects. Use of these diagnostic criteria should facilitate the search for the genetic basis for CHARGE.

Unrelated children with CHARGE demonstrating characteristic ear shapes and facial features for this condition. Note that although the underlying ear structure is similar and quite distinctive, even in the same child, the exact ear shape often varies significantly between the two sides, with typical changes including a triangular concha, small lobule, and extension of the antihelix toward the helical rim, where the lower helical fold is often thin or absent. The asymmetry of the facial palsy also results in characteristic facial asymmetry with a square shape in early childhood.

Originally, the diagnosis of CHARGE association was made by using the mnemonic C-H-A-R-G-E, with at least four out of the six characteristics required to be present [Pagon et al., 1981]. Major, intermediate, and minor criteria were proposed by Mitchell et al. [1985]. The criteria proposed by Blake et al. [1998] expanded on these earlier efforts and recommended that a diagnosis of CHARGE association be considered in any neonate with coloboma, choanal atresia, asymmetric facial palsy with neurogenic swallowing difficulties, or classical CHARGE ears (Fig. 1) in combination with other specific congenital anomalies. Each of the major characteristics is rare in other conditions. When orofacial clefting is present, the choanae are usually patent, so this finding can substitute for choanal atresia, particularly if the remaining findings are otherwise characteristic for CHARGE syndrome. Individuals with all four major characteristics, or three major and three minor characteristics, unquestionably have CHARGE syndrome. Some of these features are difficult to detect in fetuses or neonates, therefore, the diagnosis need to be considered in any infant with one or two major characteristics and several minor characteristics. This often requires directed evaluation for clinically less obvious features, including a cranial CT scan to look for abnormalities affecting the temporal bones, choanae, or brain, as well as echocardiography, renal ultrasonography, and retinal evaluation.

Some characteristics of CHARGE overlap with those of other conditions, including: DiGeorge sequence, velocardiofacial syndrome (VCFS), retinoic acid embryopathy, Tanes-Brocks syndrome and PAX2 abnormalities. Furthermore, several different structural chromosomal abnormalities have been reported in some children with coloboma, choanal atresia or heart defects [Blake et al., 1998]. Consistent submicroscopic chromosomal abnormalities in patients with CHARGE association have not yet been demonstrated, and there has been no consistency in the types of chromosome anomalies reported previously. The fact that the associated malformations in CHARGE can occur with a variety of different chromosome abnormalities provides support for preserving the concept of a CHARGE association. Whether a single genetic etiology will ultimately be associated with a more narrowly-defined syndrome within this category (e.g., CHARGE syndrome) remains to be proven.

A teratogenic etiology for CHARGE association was initially suspected, but this has not been substantiated in the 20 years since this condition was originally delineated. Most cases of CHARGE association have been sporadic occurrences in an otherwise normal family. In some families there is a clear genetic component, with parent-to-child transmission suggesting autosomal dominant inheritance, and recurrences among siblings born to normal parents suggesting possible germ cell line mosaicism [Blake et al., 1998]. There has been concordance in affected monozygotic twins, discordance in dizygotic twins, and statistically advanced paternal age among sporadic cases of CHARGE, with paternal age 34 or greater noted in 43% of cases [Blake et al., 1998; Tellier et al., 1998]. No well-documented cases of CHARGE syndrome have had a detectable chromosome anomaly or submicroscopic FISH deletion of either 22q11 (VCFS), 7q36 (holoprosencephaly), or 10q25 (PAX2) [Tellier et al., 1998]. These findings all support the strong possibility that most patients with CHARGE association have a fresh dominant mutation or submicroscopic chromosomal deletion involving an unknown gene. High resolution chromosome analysis should still be performed in new and old cases of CHARGE association, in an effort to identify any associated chromosome abnormality in this condition, and FISH for 22q11 deletion should also be done when there is associated DiGeorge sequence, in order to rule out VCFS.

The question arises, if there is a recognizable syndrome within CHARGE association, what should it be called?. It is potentially confusing to have both a CHARGE association and a CHARGE syndrome, and given that Hall and Hittner each captured the most important elements of this syndrome in their initial reports, I suggest we name this entity Hall-Hittner syndrome in recognition of their seminal contributions.